Mose McQuitty & His Routebook

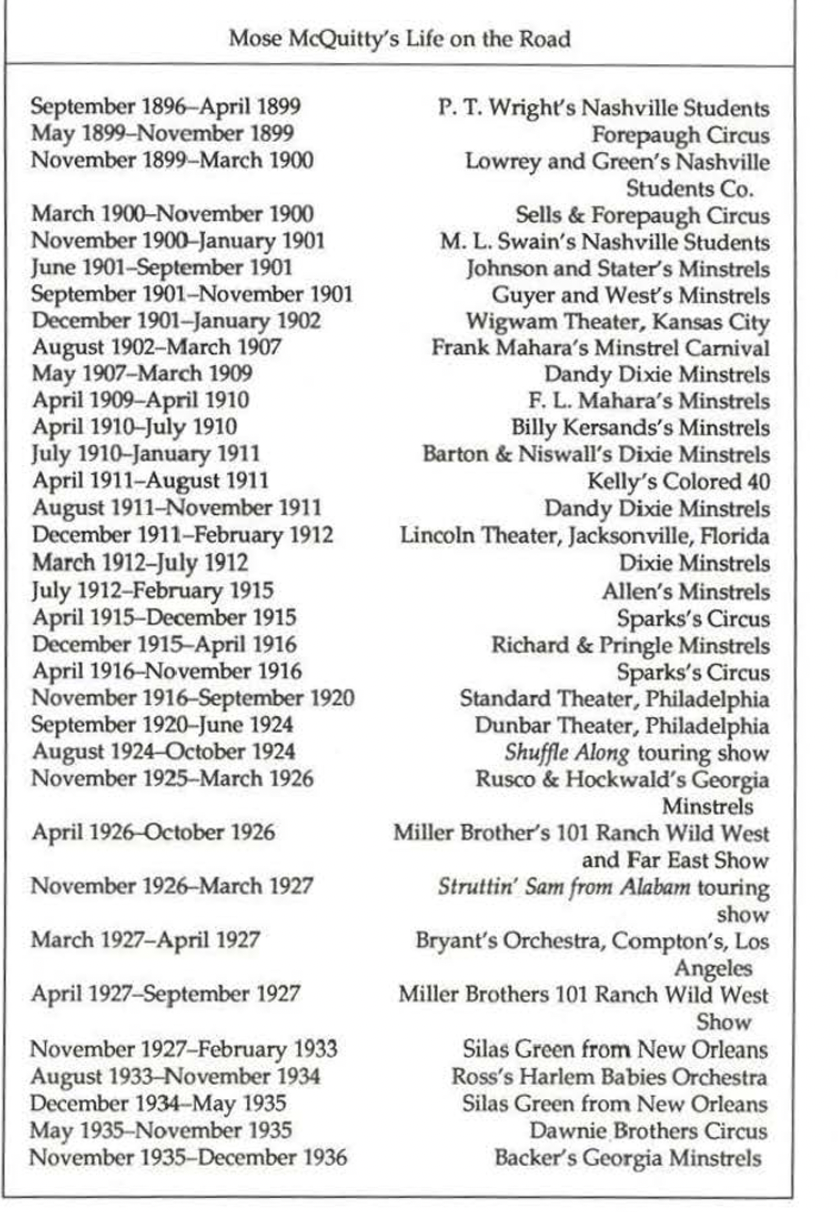

Forty years after first seeing it, I’m still convinced that Mose McQuitty’s routebook reveals one of the great American untold stories. With its recent digitization at East Carolina University, that should change, and as his career is further explored, our understanding of his long ago world will become clearer. That career left no tangible documentation in terms of recording, visual or sound, and little by way of still photographs, mostly just this incredible routebook, 40 years rolling by in his handwriting, page by page. Imagining what he saw, from the 1890s into the Great Depression, in his travels–in all 50 states and east-to-west coast in Canada, mostly by rail–is difficult enough without thinking, too, that he had with him a big baritone horn and this 12-pound routebook, as well as the burden, sometimes, of being Black and on the road in America.

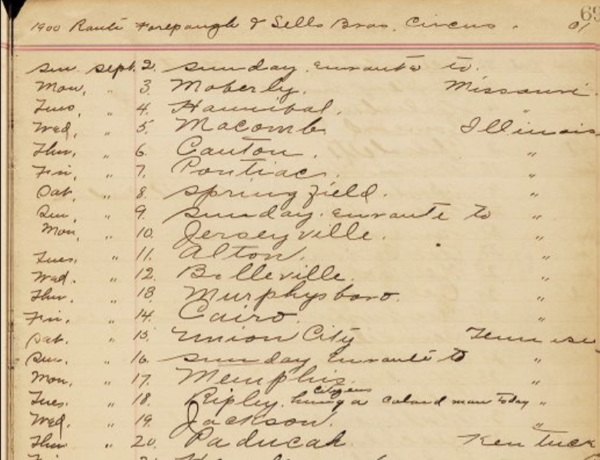

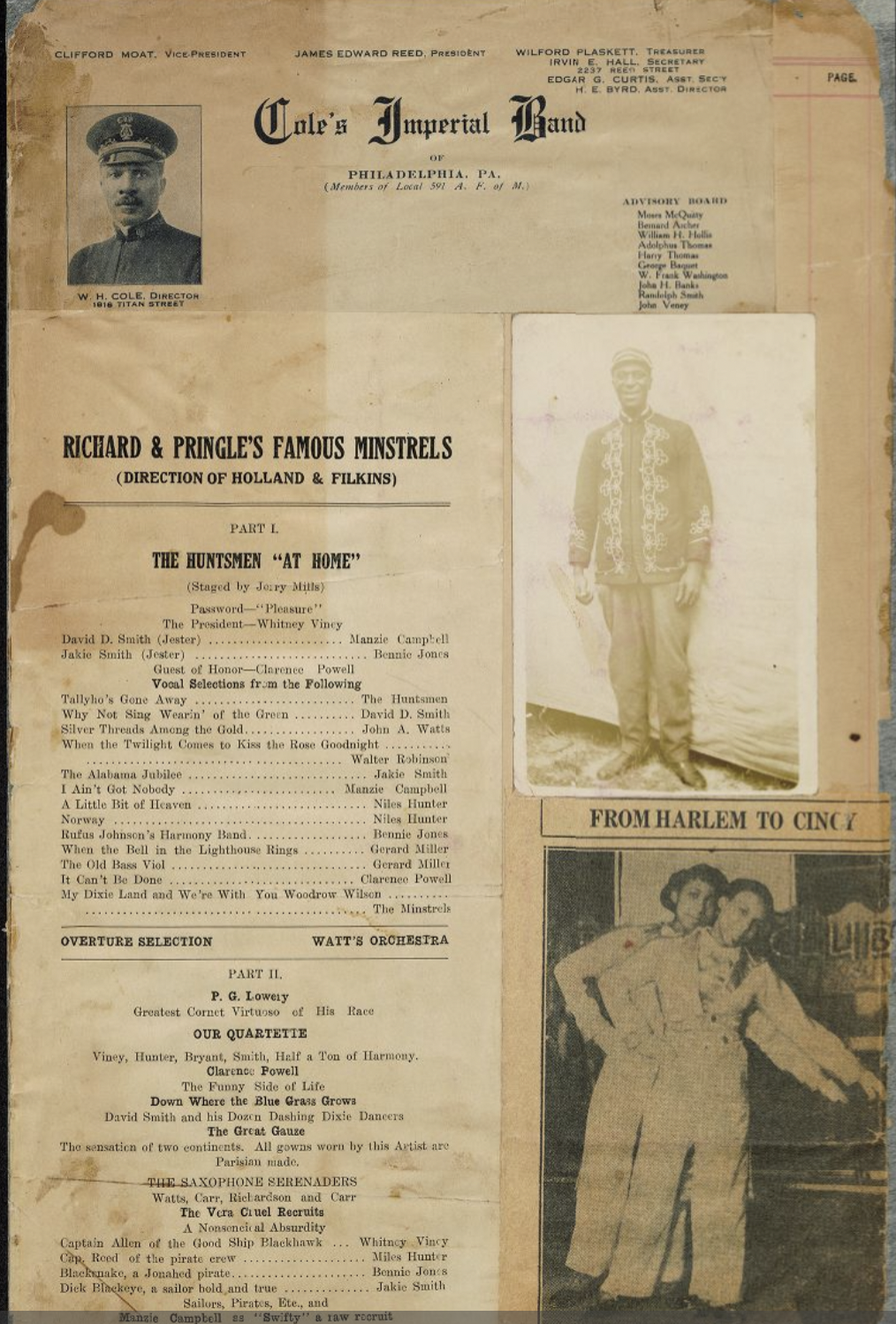

Although much of his story is only outlined in day & date notations, those specifics make it possible to develop a more complex story by tracking the histories of the shows with which he played. And occasional journal-style notations that accompany the day & dates add significantly to those histories. Some of the story that’s unfolded, so far, is not pleasant. There’s a reason he quit playing the South for many years: On September 18, 1900, he notes of his visit to Ripley, Tennessee with the sideshow band with the Sells & Forepaugh Circus, “citizens hung a colored man today,” an incident that seems for the most part undocumented. America’s Black Holocaust Museum notes three lynchings in Ripley but they are not close to this date, and another in Tennessee, on September 26, 1901, but miles away, in South Pittsburgh; those are the closest to the incident McQuitty reports. It’s also likely, given the small world in which Black traveling musicians lived, that McQuitty had worked with Louis Wright, the Richards & Pringles Minstrels musician whose lynching in New Madrid, Missouri, in 1902 was reported on extensively, especially in the Black press.

• • •

Inside cover of McQuitty’s routebook. Greenville, NC. East Carolina U, Joyner Library Special Collections.

Mose McQuitty’s life on the road had a long journey getting here, digitized. It got transcribed thanks in large part to student assistants hired through East Carolina University’s English Department and Joyner Library. Don Lennon, former director of special collections, where the routebook now rests safely, allowed it to be stored in archives stacks for many years while a long parade of students checked in, copied day and date and details, and clocked out. For a few years, I kept up with those students, and if any in the world happen upon this page, I hope they can understand in some way how important their work was.

After the transcription was completed, in the late 1990s, my wife, Elizabeth, and I created a data base that also allowed a printout of routes arranged by states. Today, you can read a chronological unfolding of McQuitty’s life as it was recorded, 1896-1937, in his routebook, or on site at ECU you can read copies of the pages broken down into the states in which the towns where McQuitty played are listed alphabetically with corresponding date(s) on which he played there. These pages also have my notes on them, and I hold out hope that I will also find that database.

Part of the package I transferred to ECU in 2023 is a set of files for each of the shows on which McQuitty played, as well as for the major theaters where he worked for extended periods of time.

When Mattie Sloan gave me the routebook, at the end of our first meeting in 1986, it was clear that it had been rifled, some of its first pages removed. It starts abruptly now with a November 1895 date with P.T. Wright’s Nashville Students in Strausburg, Nebraska. Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff have helped immensely to fill in details of McQuitty’s earlier musical work. They document McQuitty’s performance with the MCabe & Young’s Minstrels, directed by W.A. Mahara, beginning with the opening of the 1892 season on October 1 in Elgin, Illinois. Mahara’s Colored Minstrels, Abbott and Seroff write in Out of Sight, “remained a powerful force in African-American minstrelsy until W.A. Mahara’s death in 1909,” and that they are “probably best remembered for having served as a launching pad for W.C. Handy,” who documents some of that work in his autobiography, Father of the Blues. Handy joined Mahara’s in 1896. Its cast included several performers who would work with McQuitty over the next 40 years, including P.G. Lowery, George Moxley, Billy Young, Al Watts and Harry Fiddler. Until 2019 and reading Out of Sight, I could only guess at what had happened in McQuitty’s life prior to November 1895 and wonder what documents of those years from his routebook had been taken. He was so good, though, that’s easy to imagine there were some sweet handbills, photos and notices among those first pages. Although I still don’t know anything of his pre-show business life, it’s easy to see that he was smart, well-educated, and an excellent writer–he was among a small group of leading African-American show folks who reported regularly on their lives on the road to the Indianapolis Freeman and Chicago Defender, especially during the early years and into the 1920s. A good book could be compiled containing the best of that creative nonfiction, by the likes of Tim Moore, Coy Herndon, Sherman Dudley, McQuitty, and their peers.

McQuitty died in Fayetteville, in a house owned by Fat Winstead. Mattie Sloan recalled the day he died: “I got one of Mose’s whiskey bottles when he died–people were getting his stuff. He was sitting on the porch while I went around the corner to get some chitlins and I came back and he was dead. He never missed drinking–eery day of every week. Hog Head wanted that book–but he’s in prison now.” McQuitty, fearing his routebook would be lost to fire or theft, had already entrusted it to Mattie, who’d held onto to it for fifty years before I came calling. She was able to fill in a few details about his life, but not his hometown.

One story, how she met Edna, McQuitty’s sweetheart, in the Fayetteville neighborhood where Winstead owned several rental properties, is classic Mattie Sloan story-telling technique:

There was some fellow next door to the tent, Pops, I named him, had this gray mule. He sold liquor, and he was a very good cook, and he had one thumb, one of his thumbs was cut off. He had made this corn bread and I had cabbage and everything, and he said I’m gonna give you a break–I’m going to cook today and you won’t have to cook today, you just go ahead and do what you got to do, go on downtown and do some shopping. So I went on and let him do that cooking, and that night we all be ready to eat and that’s when I met Mose McQuitty’s old lady.

Over the course of several subsequent visits to Mattie Sloan’s home in Laurinburg, she cleaned out drawers and boxes of other “paper,” she always called it: “I found some more paper for you,” she’d say. Programs, playbills, ticket stubs, show licenses, newspaper clippings, show cards and calling cards, photos, correspondence, payroll books for Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels in the 194s & ’50s. That’s all part of the Mattie Sloan collection at ECU. Some of it is from McQuitty’s routebook, but much is from her own collecting, what survived the years at any rate. She had her own routebook:

I got my diary in Norfolk, Virginia–you ought to have seen it. Started it in 1931, the day I joined the show. That’s what you do. Lot of people on the shows wanted to keep a book. Mason, the trumpet player from over seas, he kept one. I kept mileage in mine. I wanted to collect everything I got my hands on. I got gobs of eye glasses, coins, books, records, dishes. I West Virgniia in. that little half moon town, it had a jail house and all the stores down in the valley, a court house, the p;ost office, all in one building. You had to climb tht hill for the show. And this lady I stopped with? She gave me cins you wouldn’t believe.

• • •

I remain hopeful that Mose McQuitty’s routebook will get the kind of state-by-state / town-by-town interactive web page it deserve. Maybe that’ll still happen. But meanwhile, I’m glad to facilitate anyone’s research interests in McQuitty’s world. You can get a feel for it from the next few images from these early pages of his routebook, all now online and courtesy of ECU’s excellent Special Collections work. And, like me, you can wonder what kinds of annotations he might have made on his routes between October 1, 1892 and November 2, 1895–and did he work with other shows prior to those dates?

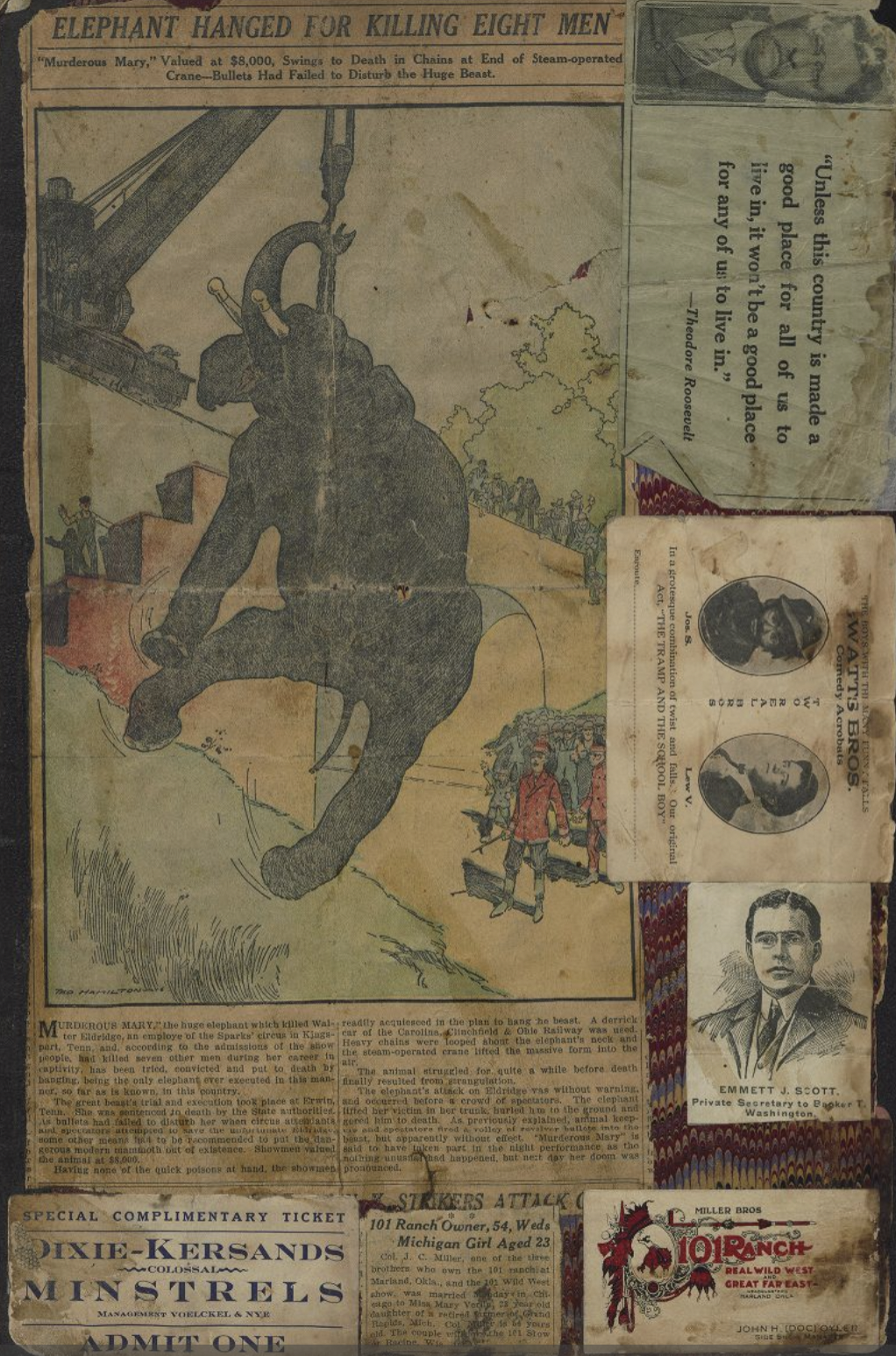

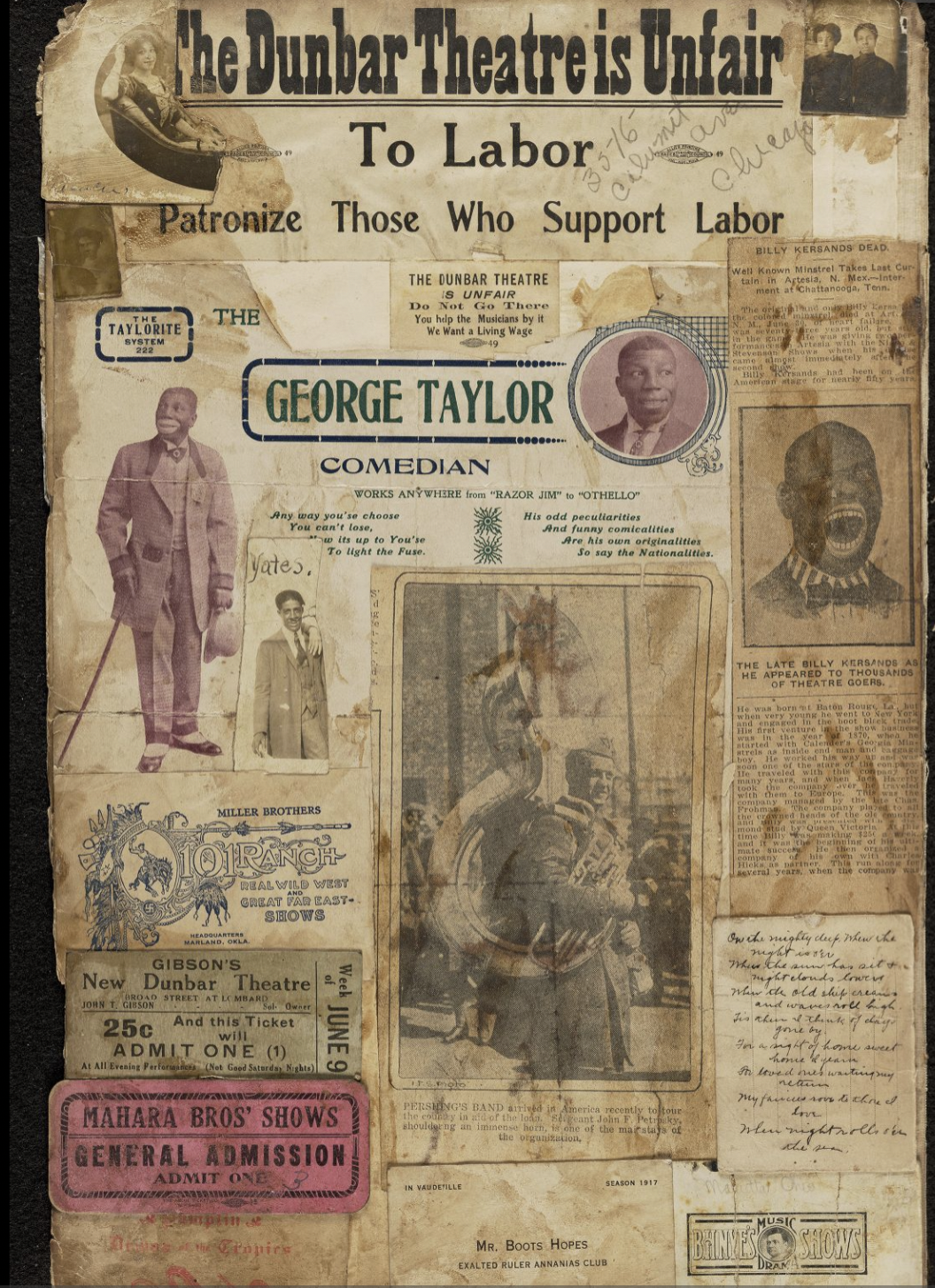

McQuitty worked with the legendary Billy Kerands, was with the Sparks Circus when it hanged the elephant Mary, and he performed with the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch in its sideshow with the Georgia Minstrels. Mose McQuitty Routebook & ephemera. Special Collections. ECU.

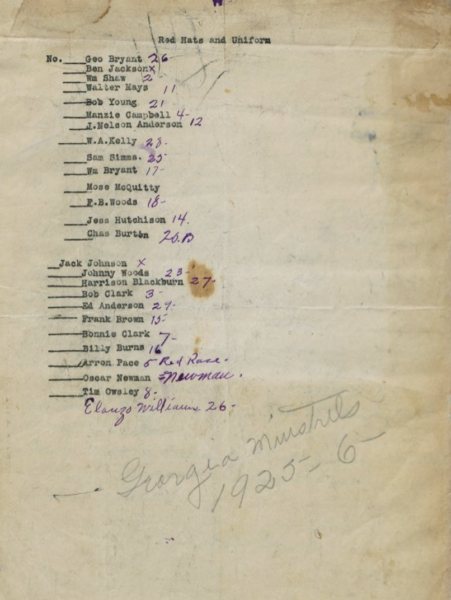

McQuitty’s 1925-26 tour with the Georgia Minstrels was well documented by Tim Owsley, who was a regular correspondent for the Chicago Defender and reported almost weekly on the band’s adventures. Mose McQuitty Routebook & ephemera. Special Collections. ECU.

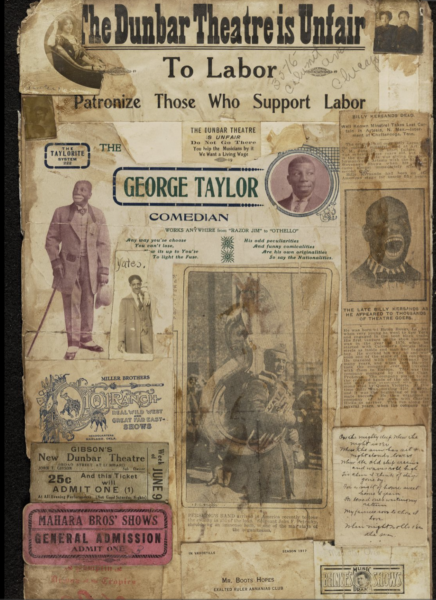

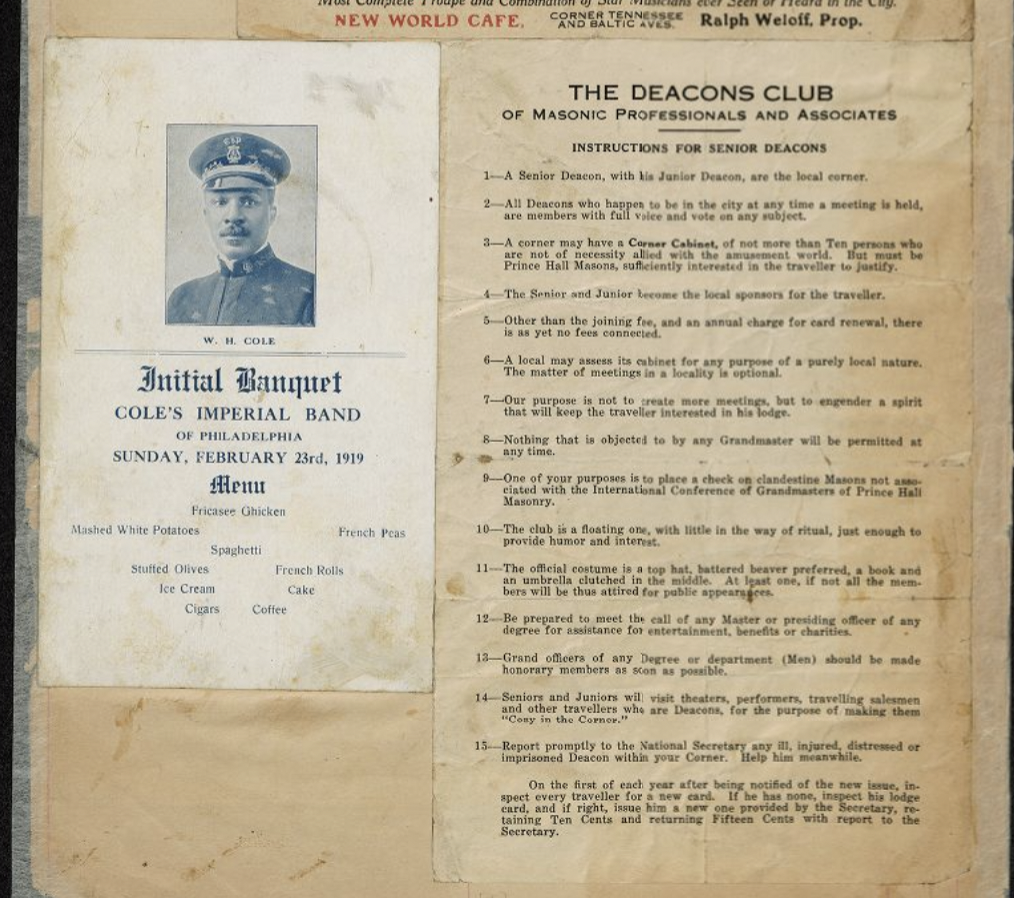

Scrapbook page from the first part of McQuitty’s routebook, which also includes a compete listing of Deacon Club corners. He & Della operated on in Philadelphia. Mose McQuitty Routebook & ephemera. Special Collections. ECU.

Inset at right is a photo of McQuitty in his personal uniform. Mose McQuitty Routebook & ephemera. Special Collections. ECU.

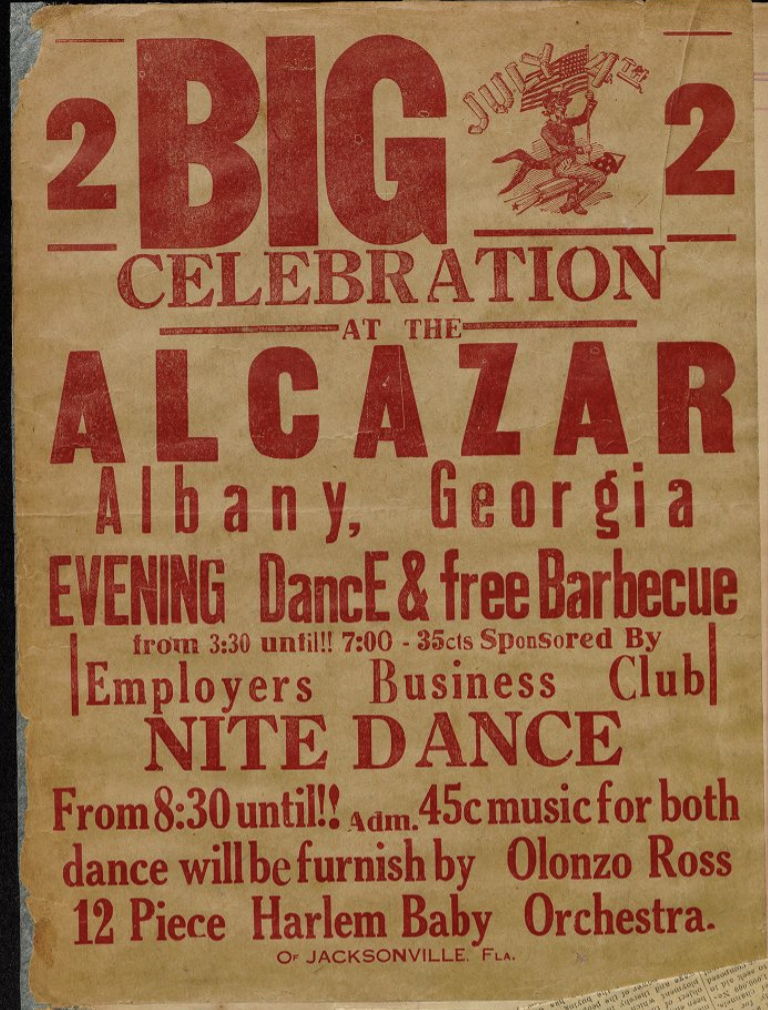

McQuitty played with Alonzo Ross’s Harlem Babies Orchestra 1935-36. Mose McQuitty Routebook & ephemera. Special Collections. ECU.

Inside front cover collage in Mose McQuitty’s routebook. Boots Hopes was the world’s fastest liar. Mose McQuitty Routebook & ephemera. Special Collections. ECU.

1st page below of an article that is on line here.

Sources

Abbott, Lynn and Doug Seroff. Out of Sight: The Rise of African American Popular Music, 1889-1895. Jackson, MS. U of Mississippi P, 2009.

Handy, W.C. Father of the Blues.

Sloan, Mattie. Personal interviews. Laurinburg, NC:

–July 25, 2025