–this page is under construction–

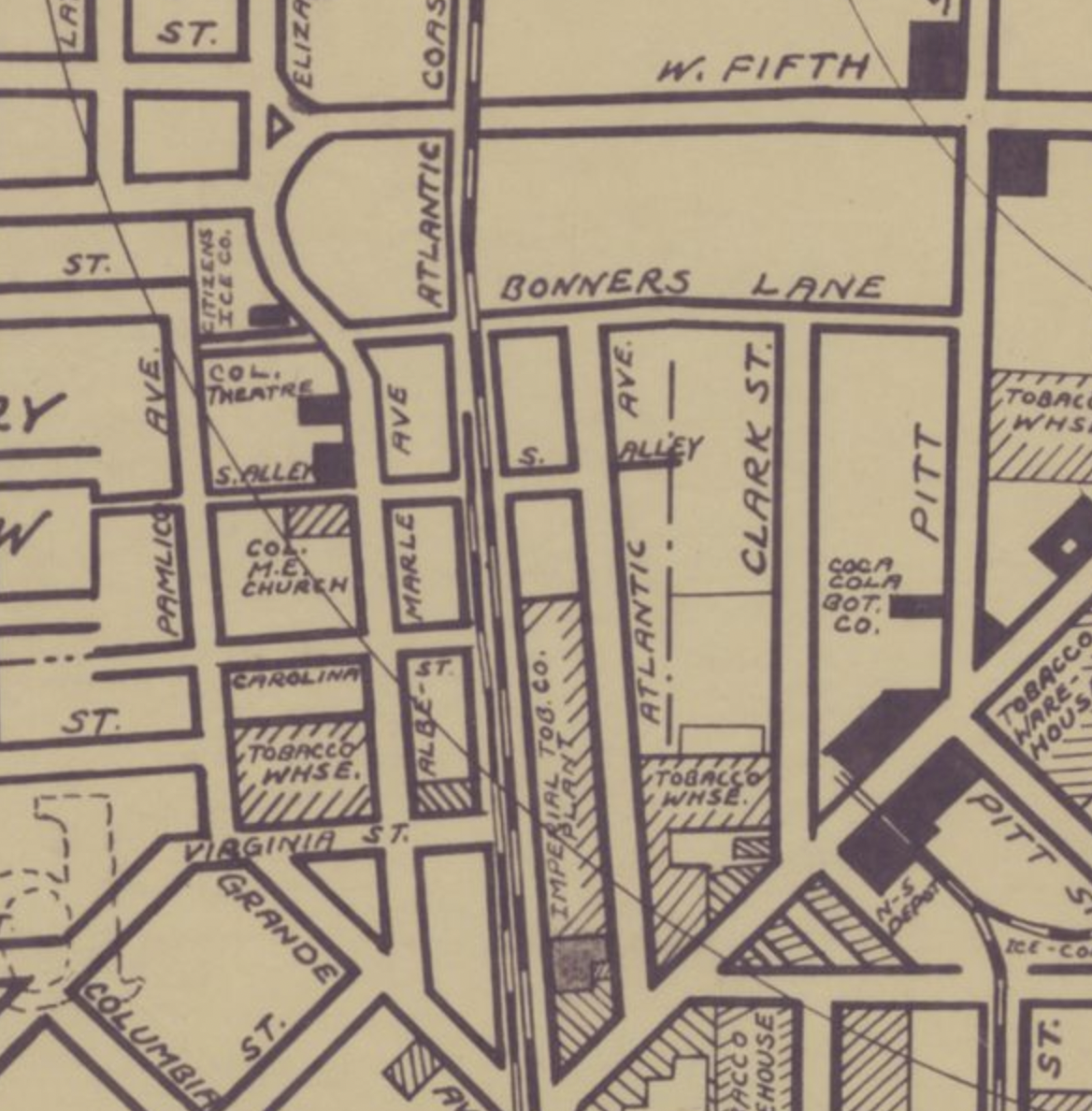

“The Block,” Filmore Bells says, “was about two blocks long” on Albemarle Avenue, from Virginia Street to Bonners Lane. His daddy, Grant Bell, ran a restaurant that, with its next door neighbor the Plaza Theater, anchored Greenville’s West side business district from the 1930s into the 1960s. Filmore Bell speaks like the neighborhood historian that he is, factually emphatic in his memories, expressive with his hands. He tells great stories and enjoys an audience. “I’m a talkative fellow,” he’ll slip into one of his later quick narratives, full of asides. He punctuates many of his sentences with “what not,” as almost an apology that he’s not going on and on about the topic at hand–several times in transcripts of his interviews for the UNC-TV documentary Boogie in Black White, you’ll see “blah blah blah” or “lots here that we can’t use” and once, “I tried to keep going with this because it was interesting but it just can’t be used.” [Those raw tapes are in ECU’s special collections]. When he’s listing, he’ll look up and slightly away like he’s reading names or places off a scroll. “There were businesses on both sides of the street at that time,” he continues, “and the businesses were Bell’s Restaurant, the Plaza Theatre, the Pythian Hall, Paradise Cafe [which he pronounces ‘calf’], Shiver’s Shoe Shop, and City Pool Room, Quality Eastern Oil Company, and the Red Rose Club–it was about the liveliest.”

detail from map of Greenville, 1933. ECU Digital Collections.

Bell was a young man during the Block’s formation, and by the time he entered the U.S. Army during World War II, its reputation as a great place for music, musicians, shows, and fun had grown. Mattie Sloan, a manager with Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels, recalled it as “a young New York town.” Willie “Ash Can” Jones, a dancer with Irvin C. Miller’s Brownskin Models, loved playing Greenville, visiting, hanging out before and after shows or between them if he were close enough to get to Greenville; he secured several musicians and dancers for acts he was managing while traveling through the region. Without prompting in his Philadelphia home in 1987 , he vividly described Ma Bell’s hospitality and food.

The Block was liveliest on weekends but it also hosted big concerts some of the biggest touring national recording Black artists–usually at the Star Warehouse on 9th Street but also in tents on the Block or, occasionally, in the Plaza–whenever they might be scheduled according to a traveling act’s tour. I ask Bell who he remembers from those shows. He says, “There were so many: Earl Fatha Hines, Tiny Bradshaw, Andy Kirk and the Clouds of Joy with Mary Lou Williams, and out of Charlotte you had Jimmy Gunns, you had the Carolina Stompers out of Wilson, you had the Blackhawks out of Kinston, the Puff Stompers out of Elizabeth City and the Sunset Royal Entertainers out of St. Petersburg, Florida.”

He describes what he calls “the warehouse days”: “At that time it was segregation; they would have a rope running midway of the warehouse and one side would be for white and one side for coloreds. But sometimes some would go under the line and here would come the police and run ’em back where they’re supposed to be at. That’s how the warehouse days were. And they would have the stage midway between both lines, and that’s the way it was.”

Millard Filmore Bell’s parents, Grant and Rosa Bell, began selling stew beef, rice and peas –one local said he was known as “the stew beef king”–on Atlantic Avenue beside the Imperial Tobacco Factory and Warehouse, shortly after World War I. They bought a lot on Albemarle Avenue in 1920 and built their first restaurant there in 1925. The Plaza Theater was built next door soon after. Through the Depression, the Block remained principally the Plaza, Bells’, the AME Zion Church, and the Pythian Hall. Bell said the building most everyone recalled as Bells’ was their second, the first having burned down in 1935, when he was 16.

Charles Shiver developed one of the first of the “new” businesses, opening his shoe repair shop in 1939; he said that most of the buildings that became the Block, like his, were moved there from elsewhere.

Charles and Louise Shivers also had precise memories of the Block and its environs. They are both well-spoken and polite, and funny in ways that come out subtly as we talk in their living room–he’s mostly dead-pan in a low basx, she a bit mischievous, her voice on occasion lilting. He especially is sometimes more brave than bitter, as he might have been when he matter-of-factly tells the story of how he got his first shoe shop, so perfectly understated that its power is not easy to catch at first. It could not have been delivered better had it been rehearsed; perhaps it had been.

When I started on the Block, it was a result I was employed downtown in the shoe shop, and it happened I had fixed some shoes for Mrs. Meadows, she was wife of the President of East Carolina University [Leon Renfroe Meadows, ECU’s second president, served from 1934-1944], I repaired a pair of shoes for her, but at that time we couldn’t face the white customers in the shop, and the other white employee waited on her, and she compli- mented the work so much, the work that I did he got credit for, and this got me so upset I told my grandmother [Pattie Elizabeth Kearney] if I could do work like that to please the wife of the president of the university, then I could make a living at it and if she didn’t make some arrangements for me to go into business, I was going to leave town, so she got to work, and she got Mr. W.C. Cox, she talked to him, he owned the property out there [on the Block] and there were some vacant buildings down where the warehouse is now. He bought that building and had it pulled up there with the turnstile and the mule and so forth and they rolled it up and set it up there and that was the only building in this area at the time. So it had two little windows on the front—that’s when I went into business—that was late 1939. I operated it util I went into service.

Almost like a set up routine, Louise tells her Block story, straight-faced and near-perfect in its details, and at its beginning, a little odd: “I was one of the first persons to work on the Block in a beauty shop. It was called Midgett’s Beauty Shop. I operated the shop, and Charles had the shoe shop next door, and there was a little peep hole through his shop I didn’t know was really there. He could look through this hole and see a few things that were going on in the beauty shop. And we had about five or six booths in there. One of the girls, Mary Louise Butler, she’s dead, the late Mary Louise Butler, said I think you’re getting a secret admirer. I said What you talking about? She said, I think Charles Shiver is looking in that peep hole at you. Am I right? [She looks at Charles and smile, and it looks like he’s a little surprised by this memory, too.] And from then on, we started a little courtship—we had been knowing each other all along.”

Charles says, “There was a party, that’s when we started going together—”

Louise imitates Charles: “I know who I’m taking to the party tonight” and switches back to her voice, “My birthday party—and sure enough, he was at my door knocking, that was 1940. We didn’t court long before we married. It was ’41.”

She adds: “When Earl Hines and Mary Lou Williams came back for the second time, not the first time, I did Mary Lou Williams’ hair, and this girl who worked in the shop with me at the time gave Fatha Hines a manicure. And we were very elated over that, because the people were all on the outside looking to see what was going on in the beauty parlor, because they thought we were really something to be able to do the celebrities’ hair and manicure.”

I ask her about Mary Lou Williams and she says, “She was a very pretty girl, and she had very very long hair. I had not been really accustomed to doing hair that long. It was pretty at the dance, and she was very happy, because she said in the North, she couldn’t get the type work she was getting in North Carolina.”

Traveling shows also performed in tents on the Block, or in the Plaza, which also hosted talent nights, beauty pageants, boxing matches, and vaudeville shows like Irvin C. Milller’s Brownskin Models. Bell said, “Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels, when they came to Greenville, it was put up on the Block, at the site where the Roxy Theater is now. But Silas Green, they had their special trains they would come to Greenville with and they would put up on Tenth Street, and when Silas Green would come to town, they would have big parades on Main Street, Dickinson Avenue and Evans Street. Silas Green’s was the best–they had the prettiest girls and what not.”

Despite being called a “minstrel” show, Winstead’s wasn’t much different from Silas Green from New Orleans, which wasn’t much different from Irvin C. Miller’s Brown Skin Models: they were all traveling vaudeville shows with pretty women in a chorus line, a good band, a couple of comics, and a variety of vaudeville acts. One of Winstead’s best known was Joe Frazier, of whose act Bell says repeatedly, “I don’t see how it was done, but it happened,” almost daring you with each assertion to doubt him.

But like the excellent storyteller that he is, Bell warms up his audience with a lesser Joe Frazier tale that begins with a question about what else he remembers about acts on the Block. “Richard Hardy got hypnotized in a store window,” he says, deadpan, “and he stayed hypnotized for about seven days.”

Who did it? I wondered.

“Joe Frazier. Joe Frazier was somebody who came to town, and he hypnotized Richard Hardy, he hypnotized him for seven days. It was an advertisement for his show and to bring people into the clothiers, too. Yeah, Joe Frazier. Joe Frazier was buried underground for about two weeks, and he didn’t have nothing sticking out of the ground. He was buried in a coffin and didn’t have nothing sticking out of the ground except a pipe. I don’t see how it was done, but it happened.”

What made him come out? I ask.

“Well, he just was going to stay for two weeks, and that was it, that was long enough, I guess, too long for me.”

• • •

After World War II, action on the Block picked up with the return of veterans and a booming economy. Two clubs were its anchor, the SS Tropicana and the Red Rose. Louise Shiver says, “It seems they would come from the Red Rose Club, they would make a path to Bonners Lane, coming from the Red Rose Club and to Bonners Lane from the Tropicana Club, and they’d have a good time there and they’d make a beeline to the Red Rose Club back on the Block, so it was just going backwards and forward to see who was who and who was there and when. And it has been known they would stay at the Tropicana till 3 in the morning ‘cause the lights then would kind of dim, that’s what we called the after-hour club, ’cause they didn’t open till 8 or 9 o’clock.”

Charles Shiver adds: “Eventually Mr. Cox expanded and built one or two more places there, Wet Wilson’s cafe and a pool room joined together. Most of the buildings were moved there from elsewhere, you know, and they refurbished them, and that’s where several black businesses were congregated there, and it got the name the Block, and that’s where most of the younger people congregated at that time. They had the pool room, a beer joint, a shoe shop, a beauty parlor. Later on, Drum’s Hatchery was located there—they had chickens.”

Louise Shiver says, “Further down the street at the corner, the cafe–“

Charles says, “Eventually Captain B. Willie and his two sons opened a oyster bar, they served oysters on the half shell, and across the street was Rainbow Cleaners and Laundry and further down was the lot where the minstrel shows and so forth came down, and the next building was the National Biscuit Company. That was the extent of the Block.”

Filmore Bell starts remembering who’d be out: “A lot of them are deceased now, Roy Little, Jackson Atkinson, Baby Tucker, Edward Thompson, Charles Bell, Prince Hemby, Charles Shivers, just a number of people, I just can’t keep calling them, just so many.”

Louise Shiver recalls the Tropicana: “The decoration theme was a ship, the S.S. Tropicana was the name of it, it was painted up so you had the feeling you were on the ship the SS Tropicana. It was a family affair. I helped her run the nightclub business. The only thing we had was a juke box, most of the entertainment was music and soft lights and alcoholic beverages. We sold beer, we had a beer license, but we bootlegged a little bit of bourbon, and that’s what it was all about, Saturday and Sunday was the only time we did any business that came to anything. And the youngsters enjoyed it–it was an outlet for them. We had a strict rule for school kids: when they got their diploma, they could come in, but not until, so on graduation night, they’d all flock to the Tropicana with their diplomas in their hands.”

Wet Wilson’s was a small juke joint with a popular cafe, run by Sylvester Wilson, but by far the main attraction on the Block was always Bell’s Restaurant.

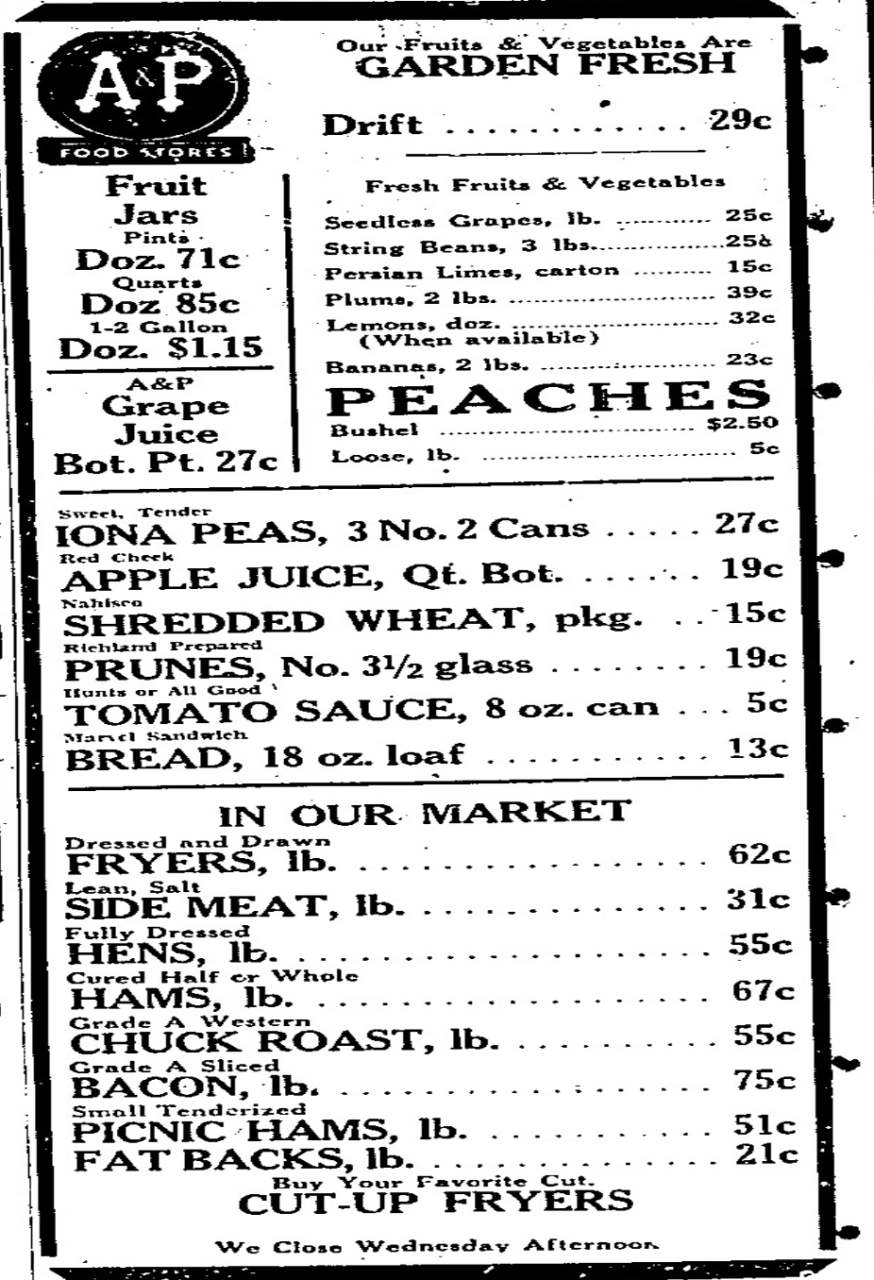

Charles Shiver says: “Grant Bell was a marvelous person, nobody went hungry, I mean if you didn’t have any money, you could go there and get a meal. Of course it didn’t take much money to get a meal anyway. He was known as the Stew Beef King. He served you stew beef and rice for 15 cents and you could get a belly full—you wouldn’t leave there hungry. Grant really fed a lot of people in this area.”

Louise Shiver smiles broadly as she adds: “You could go to Bell’s Cafe and get a sausage sandwich for 5 cents and then he would keep a big pot of gravy he would put over there and he would dip this sausage sandwich in the gravy, and say ‘It’s good, eat it.’ 5 cents, 10 cents, if you got a 10 cent sausage sandwich you had a meal. Plus he made what you used to call heavy bread, bread pudding, and you could get a big slice of bread pudding for a nicely and then. Buy a 5 cent Pepsi Cola it would carry you through the day. You had nothing to worry about ’cause you would be really filled up. All this, the kids really laugh about it now but it was so very very true. All at the cafe, they were very fine people.”

John Warner’s Plaza Theater was the second mainstay of the Block, and you get a glimpse of its steps and the exterior of Bell’s Restaurant near the beginning of “Pitch a Boogie Woogie.” He left two interior shots with his attorney, for insurance purposes. It had become home to mischief before it collapsed in the early 1970s. I’ve not found an exterior image.

About the time “Pitch” was made, John Warner’s centrality to the Block community was diminished greatly in what was often referred to simply as “the incident,” which ultimately also changed the face of the Block. In summary, Warner’s Plaza was boycotted in about 1950 to the point of closure, and the Roxy was built and opened across the street, without anyone locally knowing that Warner was the Roxy’s silent partner.

Everyone I spoke with recalled the event, but no one had a better grasp of its nuances than Purvis Cohens, who first was pr9jectionist and manager for the Plaza, “a Jew from Raleigh who bought John out–but he didn’t really buy him out”–just a 50% interest. From Reidsville, Cohens came to Greenville to manage Haley’s interest there.

He describes “the incident”: “A local fellow went into the theater one night to get his girl out, and there was a scene developed, and John called the cops. Well, there wasn’t anything but whites as policemen back then and they came got the fellow, he’s still in town now–and arrested him, roughed him up a bit, t think he got 6monthsm too And the black community boycotted the theater. It got so hoodlums would stand out front and beat ’em up, the people that went to the movies.”

Charles and Louise Shiver fill in the story:

Charles: That was sort of tragic for Mr.Warner. He was a strict disciplinarian, he tried to maintain order in the theater and it seems that one of my good friends was there one night and got sort of disorderly and they had a policeman to come in and arrest him, and he sort of beat him up and mutilated him a little bit, and from that incident whether or not Mr. Warner was responsible, he lost favor with his patrons, and the business started turning, and it was sort of an unspoken thing, and they boycotted the theater, the word circulated Don’t go to the theater on account of the incident and people just quit going to the theater. That was the demise of the Plaza.

Louise: We would watch from the beauty shop, we would really watch who was going there. They were having some very good pictures at that time and we wanted to go but we wouldn’t go, and there was some people who were still going to the movie.

Charles: Probably somebody didn’t know about the incident.

Louise: Some of the ladies would come over to the beauty parlor and say What’s happening? No body’s going to the movie anymore and we’d have to tell them what happened. One lady said, Oh I didn’t know that—I wouldn’t have gone. Because it’s a small town, it’s true, but the word doesn’t get out on everything.

The Roxy was built then across the street, Warner maintaining an interest in it and in the Block; the Plaza fell down. The Block thrived and then it faded and now it’s mostly vacant lots again.

• • •

I regret that I did not find reason to remain in contact with folks like the Shivers and Filmore Bell. Charles Shiver called me once, after Louise had died. The city wanted his house, he said. It had been his grandmother’s, built about 1900, where Princess White and Witty and Wiles and other once-renowned Black vaudeville stars had stayed for the night because Greenville had no public accommodations for Blacks except for private residences like his–and the recently disappeared place at the corner of Memorial and Third Avenue that for years had a sign in its yard saying it was the city’s first Black motel. He wanted to know how he could be re-assured that it would be preserved, as he’d been told would happen as the city of Greenville arranged for its purchase. He was moving to a home, he said, the way folks say “home” when it’s not really one, but a last stop place of care. Once “the largest and most historically significant house” on Clark Street, its site is now a parking lot.

Bell’s, the first of the Block’s retail businesses, was also among its last. The Shivers, Red Eaton and Filmore Bell all agreed that it did fine into the 1960s, but as in much of the rest of the country, as previously Whites-only businesses opened their doors and society became increasingly integrated, Black business districts began to fade. Among the last was the Roxy, which had already ceased operations as a theater before John Warner died in 1972. Bill Shepherd and the Greenville arts community transformed its space a few years later, but they couldn’t save the Block.

• • •

Sources

Bell, Millard Filmore. “Ulysses Grant Bell, Sr. and Rosa E. Gray Bell.” Chronicles of Pitt County. Greenville, NC. Pitt County Historical Society, 1092: 176-177.

Cotter, Michael, editor. “161. Houses , 600 block Clark Street.” The Architectural Heritage of Greenville, North Carolina. Greenville, NC: Greenville Area Preservation Assoc., 1988.

Eaton, X “Red.” Personal interview. Greenville, NC.

Jones, Willie. Personal interview. Philadelphia, PA. DATE?

Lathan, Sam. Personal interview. Wilson, NC. 13 Apr. 2024; telephone interview 22 Apr. 2024.

Myers, Bill. Personal interviews. Wilson, NC. 13 Apr., 25 Apr., 30 Apr. 2024

Shiver, Charles and Louise. Personal interview. Greenville, NC. DATE?

Sloan, Mattie Barber. Personal interviews. Laurinburg, NC. DATES

–July 26, 2024

Greenville Daily Reflector July 25, 1947