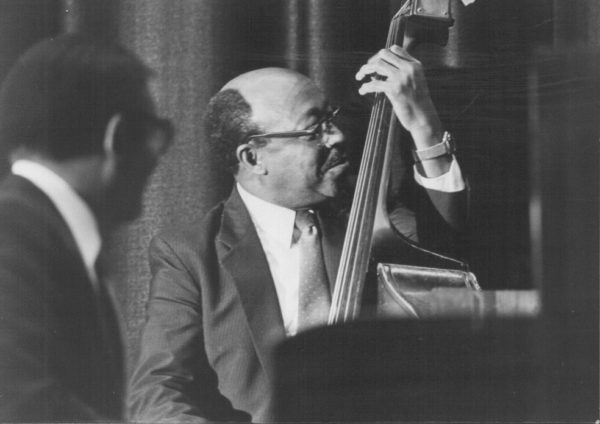

Charles Woods, UNC-TV, 1988.

Charles Woods, bass (1923 – 2000)

Charles Woods was the youngest of four born to Haywood and Etta Gilchrist Woods in Greensboro, “almost on the campus of A&T,” he said, on Memphis Street [now Bluford] just two blocks from campus. It was a neighborhood rich in cultural arts enhanced by A&T and Bennett colleges and the nationally prominent Black artists and intellectuals whose appearances they frequently sponsored.

“My sister was taking piano,” he said, “and I used to sit as a little boy and listen to her instructor and I just got interested in music.” He began playing violin in the same 6th grade class at J.C. Price Elementary School with Clarence Yourse and Nathaniel Morehead. Soon he was playing tuba and then, at A&T, string bass and sousaphone. He wound up with “a working knowledge of all the instruments.”

A 1939 Dudley High School graduate, he was a completing his junior year at A&T when he enlisted in B-1, which was promised by the Navy to remain in Chapel Hill for the duration of the war. Several B-1 bandsmen recall the day they found out they were being transferred to Pearl Harbor was the scariest of their lives, and Woods was among several who married soon before leaving, in April 1944, for the Pacific war front. Nonie Cheek was a high school senior in Chapel Hill attending a local carnival with her friends when she met Charles Woods; the birth of their first child, Charles Woods, Jr., would become the event that nailed the exact date of the Rhythm Vets’ recording session for “Pitch a Boogie Woogie.” His three brothers, all born in Rocky Mount: Kennon A., Michael B., and Frederic R.

Woods was acutely aware of the significance of B-1’s role in advancing the integration of the U.S. Navy. “I knew segregation was wrong,” he said, “even as a little boy. I just hoped to see it end in my lifetime. I mean, anybody should be able to see that if I pay $1.50 to ride a bus and you pay $1.50 to ride the bus, we ought to be able to sit where we wanted. But we always rode in the back of the bus coming home from Chapel Hill [to Greensboro], and we never said anything. That was the way it was. But that doesn’t mean we thought it was right.”

Woods played in the number one dance band cut out from B-1 both in Chapel Hill, the Cloudbusters, and in Hawaii’a, the Manana Meteors. He jammed with White cadets while in Chapel Hill and “no one said a word,” he recalled. The best part of his service, he said, “was surely the fellowship we had–we became brothers in a sense.”

The Tunesters in Hawai’i [L to R]: Charles Woods, Thomas Gavin, Walter Carlson, and Melvin Thomas.

After the war, he returned to Greensboro, his studies and the A&T band, which was led by Walt Carlson, his friend, Navy-mate and fellow Rhythm Vet. Like most area musicians, he played with the Max Westerband orchestra, which was still billing itself as the “king of swing” after the war. But he was one of the first from B-1 to pick up bop, and when the Artists Guild opened, he became their regular bassist. “It was quite an elegant place,” he said. “John Ray was manager, a goodd friend. It could’ve competed with some of the finest clubs today. It had several private rooms, the Blue Room, the African Room, the Chinese Room. I played there at least twice a month, almost always with Jehovah.”

Woods graduated from A&T in May 1947, majoring in business education with a minor in music. His business skills made him the band’s de facto manager, and he was often the contact for booking gigs. “At that time,” he said, “musicians were getting what we called ‘ten cent’–that was ten dollars [each] for an engagement. And if there were 8 of us in the Rhythm Vets, and we got a gig that paid us $80, we thought we were really in the money.” For “Pitch,” they made $150.

For him, traveling to Greenville for the recording of “Pitch a Boogie Woogie” was “just another engagement,” he said, except in Greenville that July night in 1947, his mind was clearly more on his wife and their soon-to-be born son: “Mr. Warner would take me to his home about every hour or two so I could call my mother in Greensboro to see how my wife was doing. Finally, about the third call I made I found out that I was the father of an eight-pound bouncing boy my mother told me. And Mr. Warner was very nice about carrying me to his home to make those telephone calls. I can only remember how nice he was to me. I found out my son had been born from his house, then I had to go back and do more music.”

Like other Vets, the “Grand Finale” in “Pitch” pleased him the most: “I can remember Mr. Warner telling us, ‘You’re on your own,’ and the fellows in the band were allowed to improvise. As we played our last number, each person in the group took what you call a solo. And it was just, it was more or less letting our hair down after having played with the charts” for so long.

Another vivid memory of that gig–shared by several others–came on their night ride to Greenville: “We were very young and had no regard for speed, and Buck Gavin and I used to race. Buck thought he was a mechanic, but his car wasn’t any better than mine. His looked fancier, but I had a good one. He had, I believe, a Dodge and I was driving a ’37 Pontiac, and we just had fun. There is a very narrow bridge on Hwy 98 between Durham and Wake Forest, and I do remember Gavin and I going through that bridge together, across that bridge together on three wheels, yes, we went across that bridge together.”

I wondered “Why teaching?” and if he’d ever thought about touring as a professional musician.

“Well,” he said, “with the family it was not the wise thing to do, what we could call at that time, ‘go on the road.’ And I preferred teaching to a career as far as being a professional musician is concerned. And of course, we had to choose either being a physician, a lawyer, or a teacher. Industries were not open, at that time, in 1947, for Blacks. And so really, teaching was the only thing left for us to do. In the ’40s, that’s all you could do if you were a black college graduate. There was no industry we could go into. Unless you were a doctor or lawyer, teaching was about it. I loved teaching, and I felt I was better qualified to teach than to perform.”

Woods taught in Smithfield before moving to Rocky Mount–“I intended to stay two or three years”–where he was band director at Booker T. Washington High School until integration, in 1969 when he was named co-band director at Rocky Mount Senior High School. After retiring in 1981, he was part-time band director at Our Lady of Perpetual Help Catholic School and played in the city’s community band. For over twenty years, he also led his own jazz trio, the Melody Masters, with Thomas Cofield on piano, Walter Plymouth and Leroy Knight on sax, Joe Hines on drums, and James Faison on trumpet. For 27 years, he worked summers as manager at Tom Stith Park and Swimming Pool.

At the Rhythm Vets reunion jam, after the re-premmiere of “Pitch a Boogie Woogie” at East Carolina University in 1987, he played the same bass–a gift from his mother after he came home from the war–he had played in “Pitch a Boogie Woogie.” “It was just like we had played last week together,” he said. “It was very good. I was pleasantly surprised.”

Sources

“Charles Lewis Woods, Sr.” Eulogistic Services [program] Rocky Mount, NC 14 April 2000.

Woods, Charles. Telephone interview. 11 January 1986.

—. Telephone interview. 16 Feb. 1985.

—. Personal interview. Rocky Mount, NC. 6 Nov. 1986.

—. Personal interview. Rocky Mount, NC. 11 July 1987.

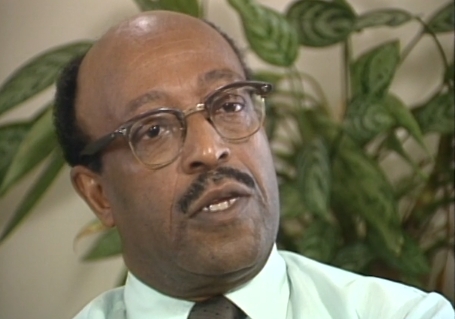

Carl Foster and Charles Woods, Greenville, NC, 1987. Photo by Tony Rumple, ECU News Bureau