Front row, 3rd from L: Samuel C. Allen. Photo courtesy of Steefenie Wicks.

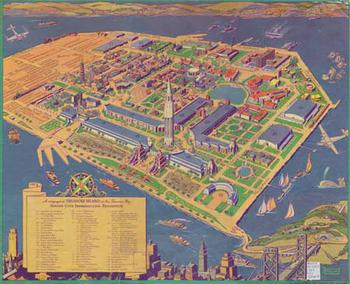

The Treasure Island Naval Station band was popular throughout the San Francisco area. The 403-acre station was built on the shoals of Yerba Buena island in the San Francisco Bay in 1936-37 for the 1939 Golden Gate International Exhibition and in 1941 its space and all its structures were leased to the Navy, which “repurposed exposition buildings, turning palaces into bunking quarters.” Some buildings were demolished, others remodeled to accommodate new needs: “The fair’s food and beverage exhibit was converted to a mess hall that would eventually serve food to over 7,000 men an hour and seat up to 3,000 at once.” The Billy Rose Aquacade was converted to one of three swimming pools and two buildings became theaters–before war’s end, a third was built.

Map of the Golden Gate Exhibition where Treasure Island was created.

The base was used primarily as a training and distribution site throughout the war. The Treasure Island band played for morning colors and at bond rallies and ship launchings. As with other Navy bands, a swing band was developed from its ranks for dance and party performances. At Treasure Island, the swing band became known as the Shipmates of Rhythm after Clyde Kerr’s arrival, and they provided music for the Naval Station’s weekly radio broadcast, “Skyway to Victory.” Kerr said that he worked with “just about all the best musicians in the country.” The Shipmates of Rhythm also played regularly at the Stage Door, a USO club that, after the war, became the Stage Door Theater.

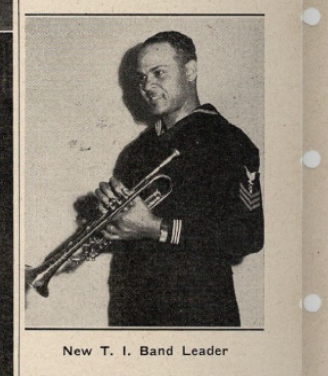

Clyde Kerr photo in The Masthead. July 7, 1945: 4. Treasure Island Museum.

Clyde Kerr, who led the first New Orleans Lakefront Navy band, was transferred to Treasure Island in 1945 and served there until after the war ended. He recalls working double duty while stationed at Treasure Island, composing and arranging for stage and traveling shows that featured musicians such as Harry James, and his band also performed behind Humphrey Bogart, Betty Grable, and other Hollywood stars–Bette Davis was in charge of booking musical acts at the Stage Door. [Kerr recalls that he was transferred to Treasure Island in 1944 but the base newsletter, the Masthead, reports that he became the new Treasure Island band leader in June 1945.]

Samuel Allen led the station’s dance band at Treasure Island band prior to Kerr’s arrival.

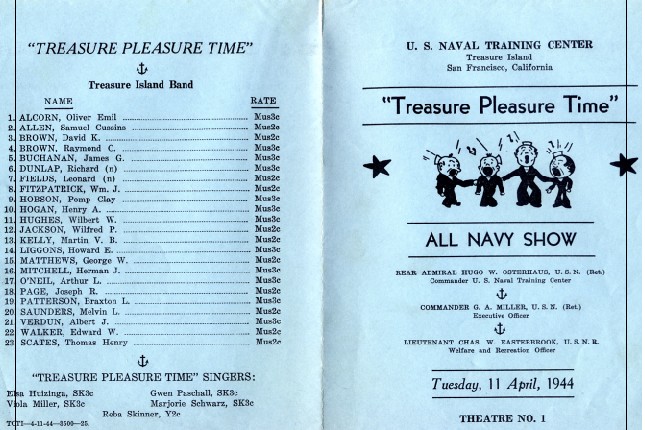

The first Treasure Island band was promised that its enlistment would have them stationed there “for the duration” of the war; they made $66 a month and rehearsed in the Savoy every afternoon before deployment. Players in that band included Alphonso Fook, Henry Williams, Wilfred P. Jackson, Ike Perkins, William J. Fitzpatrick, Joseph R. Page, Edward W. Walker, Ray Saunders, James G. Buchanan, Bill Sylvester, Thomas Scates, Arthur L. O’Neil, Melvin L. Saunders, Earl Philips, and Lawrence Fulgham. George Dixon of Earl Hines’ band was supposed to join “soon,” in August 1942.

But as with all other Black Navy bands I’ve been able to document, Treasure Island’s was broken up, its members dispersed. Jackson, Fitzpatrick, Page, Walker, Melvin Saunders, Buchanan, and O’Neil are the only original members still listed with the band in April 1944, when Allen is also named as its leader, but when he had arrived at Treasure Island is also not clear.

In September 1944, the band was presented the American Theatre Wing War Services of New York’s “highest honor” for the band’s “loyal and outstanding service” during its regular and many special peformances at events at the Stage Door Canteen in San Francisco.. The bandsmen had entertained “most of Hollywood’s stage celebrities” and performed with or opened for “many of the nation’s greatest dance bands.”

Jackson, Page, Walker, Saunders, Buchanan and Allen were still with the T.I. band when it was commended. Others, as identified in the base newsletter: P. Hobson, guitar; H. Mitchell, bass; H. Liggons, drums; A. Verdun, O. Alcorn, L. Fields, V. Kelley. W. Jackson, Braxton Patterson, Mus3c, A. O’Neil, reeds; R. Brown, E. Walker, H. Hogan, G. Matthews, Thomas Scates, (who may have left T.I. and come back), W. Hughes, brass; D.K. Brown, Mus2c, chief arranger. W. Fitzpatrick [White], bandmaster.

Piecing together Navy band histories is complicated by the lack of sources as well as the circumstances under which those sources were produced. Local newspapers are spotty in their coverage. Base newsletters, as with the Cloudbuster that documented activities of B-1, the X that documented the Algiers Naval Station’s band, and The Masthead at Treasure Island, and Treasure Island’s, are invaluable but also not comprehensive by any means. Their timeliness as well as their accuracy is not always easy to reconcile with other sources, including interviews with bandsmen and reports from the Black press especially.

Robert Johnson, who would later become editor of Jet magazine, was named the first Black managing editor at the Treasure Island base newsletter, The Masthead, he said, after the newsletter published a racist joke that caused trouble on the base. [The Pittsburg Courier reports that a racist joke printed in The Masthead in 1943 created a furor and official apology; The Masthead does not list Johnson as an editor until October 1944]. These kinds of jokes were not a problem at Chapel Hill, where racist humor was a fairly regular part of the Cloudbuster’s contents.

And because the Navy did not keep records of individual bands, it’s impossible to know for the most part when bands arrived at duty stations, how long they stayed, how their personnel changed, and if, in fact, there were other bands associated with their particular stations at the same time. One White Navy vet–Joe Pizzimenti’s dad–recalled stopping at Mogmog, in the Ulithi Atoll in the Caroline Islands, en route to Okinawa in 1945, where he played bass on a few numbers with Black musicians from “the Treasure Island band.” But such a duty station would mean that the base would be left without a band, unless there were another there. Some members of B-1 recall that their unit was at one point destined for duty at Mogmog, on which the Navy operated a large recreation & relaxation facility. Did other bands come in and out of Mogmog to fill the gap left by its not having a permanently attached band?

In 1945, there were clearly two Treasure Island bands, one White (band 126) and one Black (band 755). Band 755 was Kerr’s. How long Treasure Island had two bands is not clear, but it also seems quite possible that Kerr was associated with Treasure Island well before the base newsletter says he was there. Kerr’s recollections of performing with so many Hollywood stars makes it seem more likely that he arrived before June 1945, when Stage Door Canteen activities were winding down. It also would have been difficult for a single station band to perform all of the formal military duties required of it as well as at as many events in San Francisco as were accompanied by a Treasure Island band. Another issue arises in trying to coordinate timelines: the April 1944 program pictured here also lists Braxton Patterson in the band, but The Masthead welcomes him to Treasure Island as its “newest” bandsman in December 1944.

Courtesy of Stefeenie Weeks.

• • •

A partial muster list of Treasure Island Navy bandsmen:

Photo of Oliver Alcorn courtesy of Steefenie Weeks.

Oliver Alcorn (October 3, 1910 – 1981) played clarinet and tenor saxophone in the Treasure Island Navy band. Where he enlisted is not clear.

The musical career of his older brother, Alvin (born in 1912), who played and recorded with Don Albert, is better documented. Alvin and Oliver played and recorded with Papa Celestin’s Original Tuxedo Jazz Orchestra in New Orleans in the 1920s. Alvin later played with Sidney Desvigne on the steamer Capitol.

In Chicago after the war, Oliver recorded with Little Brother Montgomery in 1947 and St. Louis Jimmy in 1948.

The Alcorn Brothers were born to a musical family who lived in the 2800 block of Magnolia Street in New Orleans. In the 1920s, they played together in the Excelsior Brass Band, which Alvin called “a walking band” that seemed to play a jazz funeral a day. Prior to Excelsior, they played “advertising jobs” together, performing as they traveled about the city on a truck bed.

Sam Allen (January 30, 1909 – April 1963) played piano on many sides prior to the war, with the Teddy Hill and Roy Eldridge orchestras as well as with his own. Frank Driggs’ interview with him at the University of Missouri – Kansas City has not been transcribed or digitized.

Leonard Fields joined the Treasure Island band in 1943 and was noted as “trumpet soloist.” He wrote the lyrics for the 1919 hit “When the Yanks Come Marching Home” and had played with Jelly Roll Morton’s band, where he was known to be paid “higher than the usual salary because of his all-around musicianship.” A native of Louisville, Kentucky, he grew up next to trumpeter George “Little Mitch” Mitchell, who took lessons from Fields’ father. Leonard Fields studied at Chicago Musical College and was noted for his prowess on both trumpet and saxophone. Ed “Boogie” Morton recalls Fields playing sax in clubs in Louisville. Bobby Booker, who played trumpet in a band in which Fields played alto, said of him: “I never saw anybody play like him, he was really fast and used to do double and triple tongue work on the saxophone.”

Alphonso Fook played trombone and recorded with the Jay McShann band after the war.

Martin V.B. “Van” Kelly, Jr. was born in Pittsburgh on February 23, 1921 and graduated from Allegheny High School. In 1942, he married Lettie B. Hyde, became a member of Ebenezer Baptist Church, and joined the Navy, training at Great Lakes prior to service with the Treasure Island Navy band. After the war, he became one of the first African Americans admitted to the Navy’s School of Music, where he studied conducting and advanced saxophone and clarinet. He returned to Chicago and played with trumpeter Eddie Mallory and then moved to New York where he performed with the Charlie Barnett Band at the Savoy Ballroom and the Apollo Theater. He traveled as part of Eddie Rochester’s troupe and then returned to Chicago, where he played in the Billy Eckstine Band with Miles Davis, Gene Ammons, Art Blakey, and Frank Wess, occasionally gigging with Cab Calloway. In 1952, he earned a B.S. in biology/ chemistry from Roosevelt University and became a medical lab director with the Veterans Administration. After retiring in 1992, he picked up his musical interests full-time, forming the Van Kelly Trio, which was the house band at the Como Inn for five years. He recorded with Floyd McDaniel and the Blues Swingers. After moving to Hilton Head Island in 2001, he performed with several Low Country bands, including the Stardust Orchestra and a Dixieland band that played monthly gigs at the Jazz Corner on Hilton Head, where he died on November 22, 2012.

George Matthews (September 23, 1912 – June 28, 1982) was born in Dominica and moved to New York with family when he was a child. He studied tuba, trumpet, and trombone at the Martin Smith School of Music and began playing professionally in 1934 with Tiny Bradshaw’s orchestra. He also worked with Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald before joining the Navy. After the war, he performed and recorded with Fitzgerald, Cannonball Adderly, Ray Charles, Clark Terry, Count Basie, and Dizzy Gillespie. Frank Driggs’ interview with him at the University of Missouri – Kansas City has not been transcribed or digitized.

The Masthead, Dec. 9, 1944: 3

Braxton Patterson played saxophone with Noble Sissle’s orchestra prior to the war; he was known at Treasure Island for his playing as well as his arranging.

Sources

Alcorn, Alvin. Interview with Richard B. Allen, 30 Nov. 1960. Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane U, New Orleans.

Allen, John. Email to author. 24 Nov. 2017.

Booker, Bobby. Interview with editor and Frank Driggs, in Hot Jazz: From Harlem to Storyville, ed. by David Griffiths. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow, 1998.

Kennedy, Al. Chord Changes on the Chalkboard. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow, 2002.

“Leonard Fields.” Chicago Defender [Nat’l ed]. 6 Mar. 1943: 10.

“Martin V.B. ‘Van’ Kelly, Jr.” Obituary. Legacy.com. 9 Dec. 2012. Web. 6 June 2013.

Morton, Ed “Boogie.” “I’ve Got a Mind to Ramble.” Interview with Keith S. Clements. Louisville Music News, March 2005. Web. 9 June 2021.

“Navy Apologizes for Joke.” Pittsburg Courier 28 Aug. 1943: 8.

“Navy Band Is about Set with Name Aces.” Chicago Defender 15 August 1942: 23.

The Masthead. June 19444 – December 1945. TreasureIslandMusuem.org/Masthead.

“Oliver Alcorn.” ArtistInfo. Music.metason,net. n.d. Web. 14 Mar. 2023.

Pizzimenti, Joe. Email to author, 15 Mar. 2017.

White, Byron P. “Robert Edward Johnson, Jet Associate Publisher.” Chicago Tribune 28 Dec. 1995. Web. 17 July 2014.

Wicks, Steefenie. Telephone interview with author. 13 Mar. 2014.

“WW II. Treasure Island History.” TreasureIslandMuseum.org. 22 Dec. 2024.

• • •

—Alex Albright

24 December 2023