Even its title is awkward.

Even its title is awkward.

One of the soundtrack musicians said it sounded like a White man trying to talk jive.

Awkward, too, is its gender stereotyping. But its depiction of Black men performing in blackface and having been made–in 1947, no less–by a White man who was, many said, exploiting the local Black community move it beyond awkward.

That some of the Blacks in blackface come from a traveling show called Winstead’s Mighty Minstrel only compounds its issues and offenses. One leading film and culture critic said she wouldn’t speak about it. More than one scholar has denied that it depicts the real Irvin C. Miller’s Brown Skin Models. But its documentary nature supersedes its political incorrectness and its clumsy production values. There’s not another historical artifact like it; the many ways its local, regional, and national cultural narratives are negotiated between Blacks and Whites will likely never be known. My ongoing documenting of the facets of these narratives began nearly 40 years ago; it’s primarily constructed from interviews with participants and the surveying of three important Black audience newspapers, the Indianapolis Freeman, the Chicago Defender, and the Pittsburgh Courier. In its several parts, it profoundly lacks scholarly documenting mainly because the narratives I heard from the dozens of participants in this amazing entertainment world, just prior to television and at the raw beginning of Hollywood’s integration, were outside the historical contexts I could find in contemporary scholarship, especially about how long traditions such as Blacks performing in blackface persisted, and how those last shows held on to a history captured in this clumsy little film, in the form of their acts, of popular entertainment prior to the making of the first recordings–even as the ones still performing were being ignored, soon to be forgotten, and then “disappeared” by academics–their very existence denied.

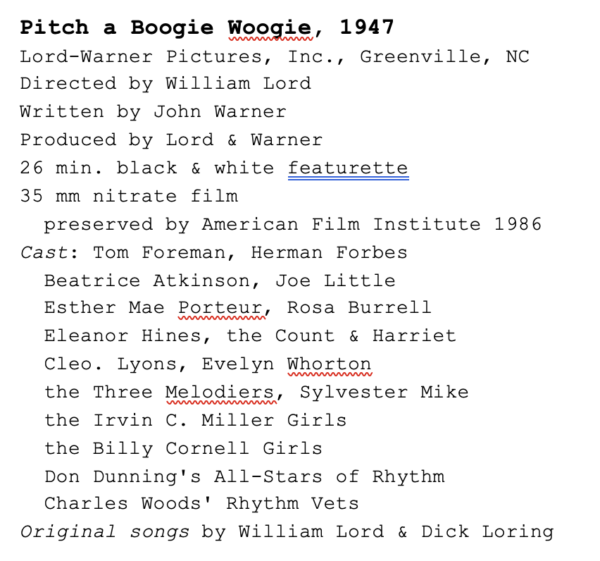

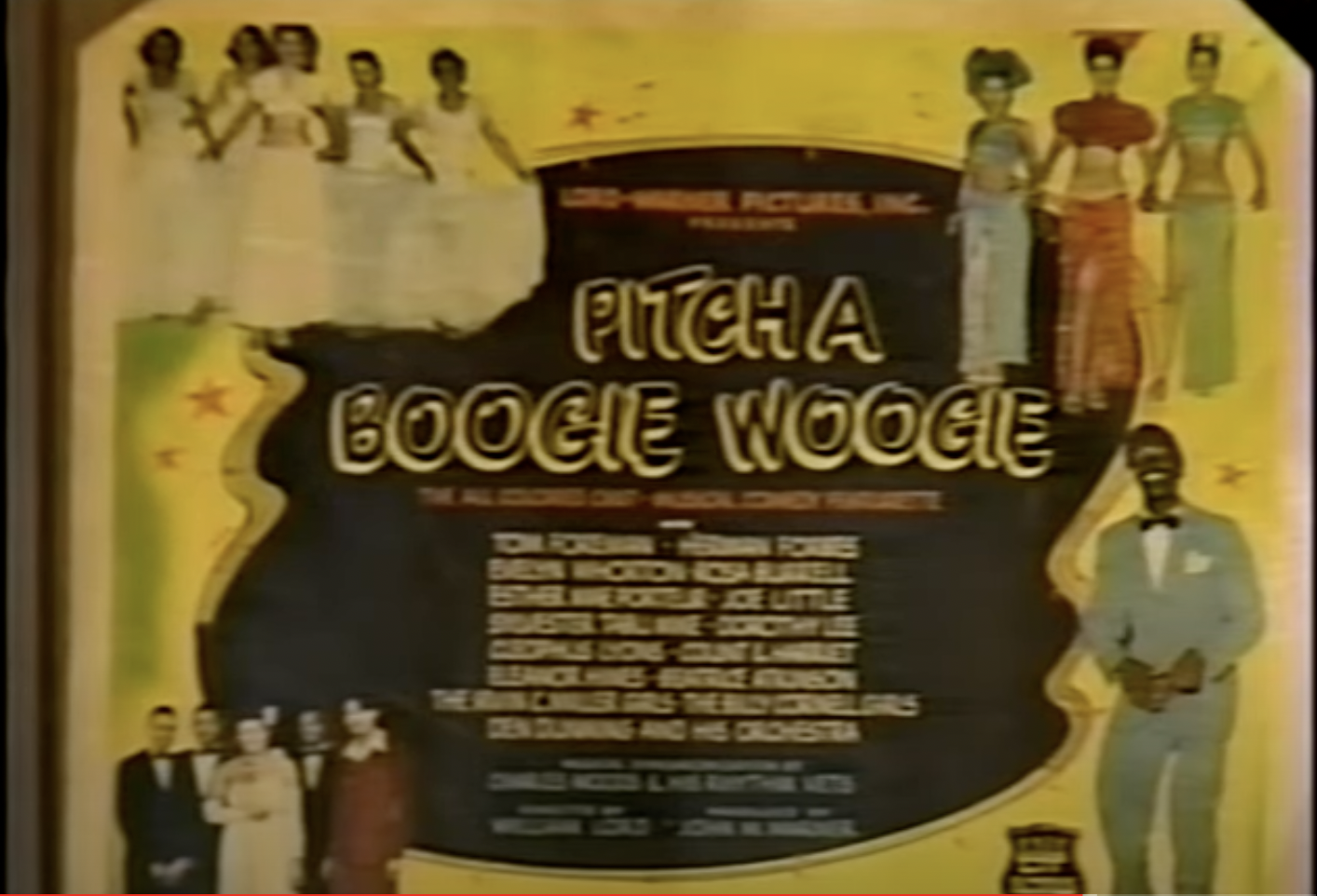

Lobby card from UNC documentary “Boogie in Black and White.” ECU Special Collections has a much better reproduction.

The rest of the world had already passed by most of what “Pitch” was documenting: a rare combination of traveling stars, Miller’s Models and Fat Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels, all performing on film what they would have been performing on stage in a Midnight Ramble or in a tent for live audiences in small towns throughout the South, where these kinds of shows had gone to die but wouldn’t.

Irvin C. Miller’s Brown Skin Models was one of the premier Harlem attractions from its inception in the mid-1920s, showcasing as it did the beauty of dark-skinned women. Miller himself is one of the least documented of the important early Black vaudeville stars and promoters; his career parallels and then goes beyond that of his better known brother, Flournoy, co-creator of the musicals that defined the early part of the Harlem Renaissance, Shuffle Along and Runnin’ Wild. The Models didn’t so much dance as pose, and that’s what you get in “Pitch”: they mix slow-moving dances with exaggerated poses during three songs, including a kind of strip-tease in one and a key-hole dance in another.

Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels harkened back to an even earlier time–the early 1900s–when “minstrel show” was completing its transition from all-White performers in blackface to shows that starred Black comics in blackface. By the 1940s, the ones still playing this kind of act had replaced full blackface with what Willie “Ash Can” Jones called “putting on a lip.” The flapping shoes, floppy hat and raggedy clothes persisted and it mitigates little to say no burnt cork was involved.

The blending of Winstead’s with Miller’s shows is also part of an unwritten history of Black entertainment that interviews with Jones and Mattie Barber Sloan, especially, have filled in. Sloan recalled that Miller’s show had traveled with them on more than one occasion, and Jones said that after World War II, the traveling entertainment scene had changed more than Miller understood. It seemed natural, Jones said, that Miller join up with someone like Winstead, who knew the routes and the performers, the best of whom, Jones said, were in a class by themselves. One of those giants, “right up there with Bert Williams,” he said, was William Earl, the comedian and dancer whose performance in the Grand Finale may offer the only known images of him. After seeing “Pitch” for the first time, in 1987, Jones was amazed that such a talent didn’t even get to speak, or make a joke for the whole film, and then comes out in the Finale just like he’d have done at the conclusion of a Models show, except live, when he came out for that last dance with the Models, he’d have brought down the house with his dance that reminded them of how outrageously funny he had been; but in “Pitch,” we’re deprived of that essential first part, making his dance even more ghostly and haunting.

So despite its clumsiness, “Pitch” is important well beyond its local significance for how it so solidly documents Miller’s Brown Skin Models, preserving three of their routines and for about 4o seconds the physical presence of William Earl. It includes the only surviving recording of Evelyn Whorton, Rosa Burrell, Joe Little, and Esther Mae Porteur, and adds a song to the short list of known recordings by Sylvester Mike. It also highlights the barely documented career of Billy Cornell, who, like Miller, enjoyed the height of his popularity during the Harlem Renaissance. It offers up the only known recordings, so far as I can tell, of Miller’s band, the Don Dunning Orchestra. And it helps establish Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels as a professional peer of Silas Green from New Orleans, their histories extending by more than a decade the generally accepted legacy of Black tented vaudeville.

What happens musically, beyond the hokey lyrics, also documents an evolution of musical styles, as the Rhythm Vets play for most of the film a big band score that, in the Finale, turns to bop and lets several of the Vets loose for uncharted solos. The Finale also includes Lou Donaldson’s professional recording debut, pre-dating by about 4 years his first New York records.

• • •

The dream begins, then it ends, and the world moves on. In “Pitch,” the ending dreams include big bands, independent movie making and, independently, movies made for Black audiences, as well as traveling Black vaudeville shows. “Pitch” is a last vestige in many ways of segregation, which takes the longest to finally die. Audiences for shows like Miller’s and Winstead’s might be separated in a couple of ways: Blacks in a balcony, if allowed in the theatre at all; or the races separated by a rope drawn down the middle of the seating. In Deep South towns like Greenville, theaters that catered exclusively to Blacks had once thrived; by 1947, Warner’s was one of the last that still made money, so much when it played movies like Cabin in the Sky that he was certain he and his brother would succeed as moviemakers. “Pitch” is also derivative of the Lena Horne short, “Boogie Woogie Dream”–both of those, however, were made nearly five years prior to “Pitch” and, more importantly, well before the post-war acceleration of social changes, which “Pitch” confronts on screen as well as on the streets of Greenville during the time it was made.

Criss-crossing the Jim Crow South in the late 1940s to make a living as a Black performer seems hard to imagine. And for these troupers, there was little hope that they’d make the jump from race productions to integrated ones in Hollywood and Broadway, even as such things began to happen–though not in the South, where after the war things would get progressively worse for a long time before they’d get any better. And none of these performers or their managers had any idea that TV was impending, that their way of life and style of entertainment was so totally doomed by so many factors.

In 1986, about the only way to find out about Winstead’s was to be lucky enough to get to know their cook and personnel manager, Mattie Sloan. Without the internet, then, I could order microfilm reels of the Chicago Defender, finding a few notes on Winstead’s and its kind and confirmation in print of some of what Mattie Sloan would tell me. Only recently did a search reveal the newspaper note that nailed her assertion–also denied by scholars–that Bessie Smith had been playing with a Winstead-owned show the night before her 1937 fatal auto accident.

With the internet, it’s certainly easier to find old news stories about “minstrels” or “Winstead’s”, even “Frank Sloan” and “Billy Cornell,” but still it seems episodic–rarely can you find start and end dates for shows, or complete and reliable biographies of their stars and producers from those Defender and Pittsburg Courier internet searches; the Indianapolis Freeman, the most important early resource on this still misunderstood and least accurately documented of American popular entertainments, is now on-line although still not searchable.

Two things happen nearly every time I run a search, and today you can combine the Defender and the Courier with dozens of other similar newspapers in your searches: first, I can’t help but wonder how thorough its scan has read my selected key words; second, how many hours did I spend reading those reels and reels and reels, photocopying and taking notes, and how much did I miss in those pre-internet searches? Still I remain grateful for that time during a summer fellowship at the Center for Black Music Research in Chicago, 1991, when I plowed through the first 25 years of the Freeman, always making copies that took in as much of a full page as possible, so that still, today, I find in them in idle hours or searching ones details of importance and amusement on the periphery of what I had originally thought worth copying .

• • •

UNC-TV’s 1988 documentary Boogie in Black and White includes the complete “Pitch” as well as interviews with cast members and locals who recalled the Greenville scene centered around what was called the Block, on Albemarle Avenue. The experience of researching this movie changed my life as it gave my career a trajectory and helped me better understand how my life had fit with the larger patterns of growing up White in the Jim Crow South.

• • •

Much of the history of “Pitch a Boogie Woogie” is rooted in oral interviews. Sorting fact from fallible memory is often difficult, and sometimes the sorting cannot happen. But often in the course of my interviews, I found documentation that verified the speakers’ claims. Sometimes the blending of memories seemed almost too much to believe. When both Mattie Sloan from Winstead’s and Willie Jones from Miller’s claimed the great and unheralded comedian William Earl as being from the cast of their shows, I thought something amiss, but then, it turns out, the shows had blended even as the world was being further divided, leaving William Earl as a formerly known constant, despite how vividly the two of them remembered his brilliance as they described him and his acts 40 years later.

THE BEGINNING

“Pitch a Boogie Woogie” premiered in Greenville, NC on January 26, 1948 in what was surely a rare event: simultaneous premiers in the same town, one for a White audience, the other for a Black. Created with a cast of local African Africans, two traveling shows (Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels and Irvin C. Miller’s Brown Skin Models), and a dance band from Greensboro (the Rhythm Vets), “Pitch” was, in fact, one of the last movies in the U.S. made exclusively for Black audiences, and its screening at the State Theater in Greenville that night was the only time it was seen publicly by Whites until it re-premiered on the East Carolina University campus in 1988. Across town, on the Block back in ’48, it simultaneously premiered at John Warner’s Plaza Theater.

“Pitch” was filmed during the summer of 1947, inside and on the steps of the Plaza Theatre, on Albemarle Avenue in West Greenville and in a tobacco warehouse nearby. Built about 1923, the Plaza was the only place Blacks could see movies in Greenville. Co-star Beatrice Atkinson recalled the Plaza premiere: “That theater was a wild and crazy place. They were having fits, clapping and screaming. Everybody loved it. For a long time, I’d hear people say, ‘Hey, there goes that girl that hit them men on the head with the rolling pin.” “Them men” were her fellow co-stars, Herman Forbes, who plays Bill as well as the intro song, “Swell Boogie,” on piano, and Tom Foreman, who plays Tom. Forbes became a career educator in Greensboro and High Point, a principal at several schools, and was North Carolin’s Teacher of the Year in 1975. Foreman was a community leader in Greenville until his death in 1978. The Greenville park that was named in his honor is across the street from where he and his wife lived for decades. Atkinson was the first original cast member I “found,” in East Carolina University’s Joyner Library, where she worked; she in turn told me about Herman Forbes, Mrs. Tom Foreman, and Huey Lawrence, the locally legendary bandleader in Ayden, who told me about the rest of the Rhythm Vets, who’d all been his class and bandmates and Navy buddies.

THE PLOT

Tom dreams he and his pal have opened a nightclub, and in his dream, he enjoys the show.

It’s a typical backstage musical, patterned after those popularized by Busby Berkeley in the 1930s: we’re treated to Tom’s dream club performances, which are sandwiched between two brief real-world scenes. Tom gets his dream-club idea from his pal, Bill, who’s just gotten back from the big city where he learned a “swell new tune.” Tom says, “Why don’t you beat it out for me?” They’re on the street, conveniently in front of a theater (John Warner’s Plaza), and as they walk up its steps, they pass a youngster playing harmonica and, in the background a policeman stopping a car in front of the locally famous Ma Bells’ soul food restaurant.

Inside, as Bill plays, Tom agrees that it’s a swell idea to open a club but worries that their wives might find out.–foreshadowing! Bill continues his boogie woogie piano piece, Tom falls asleep, and they’re replaced on screen by the dazzling Evelyn Whorton, the club’s emcee, who says she’s just gotten back from making a short with Lena Horne. “Next week, ” she jokes, “I’m going back to make the shirt.” Horne, incidentally, plays a seamstress in her 1944 short “Boogie Woogie Dream.”

Whorton, of Irvin C. Miller’s Brown Skin Models, then sings the title track and introduces the ensuing performances: songs by locals Joe Little and Esther Mae Porteur; Rosa Burrell, from Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels, who also does a fire dance; and lots more dancing: by the Lindyhopping Count and Harriet and eccentric tap dancing by Cleophus Lyons, both acts from Miller’s troupe; and several unknown and eccentric dancers from Winstead’s in a frenzied Grand Finale, with soundtrack music by the Rhythm Vets, a 9-piece dance band from Greensboro.

In the end, as the big band jazz turns to bop–Lou Donaldson taking his first recorded solo while William Earl, hardly elsewhere documented in his 50-year career then winding to a close, shows Michael Jackson how to really pull his pants–Tom’s wife enters with her rolling pin and whacks him into consciousness with it. Philosophically, Bill tells him once they’re back on the street, on the Plaza Theater steps, that he’s not had a dream: “You’ve had a nightmare!”

THE CAST

“Pitch a Boogie Woogie” starred two locals, Tom Foreman, who plays Tom, and Herman Forbes, who plays Bill. They were supported by a mix of other locals and performers from two traveling vaudeville companies, Irvin C. Miller’s Brown Skin Models and Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels (in credits, “the Irvin C. Miller Girls” and “Billy Cornell Girls“). Charles Woods Rhythm Vets were hired from Greensboro to provide the soundtrack instrumentation for songs and dances, much of which had already been filmed.

Locals included soloists Esther Mae Porteur and Joe Little, his background group the Three Melodiers, which included Eleanor Hines, and Beatrice Atkinson, who steals the show as Tom’s wife with her rolling pin-awakening from the fellows’ dream nightclub. A dozen or so locals appear as uncredited extras.

Evelyn Whorton, Cleo Lyons and the Count & Harriet were part of Miller’s Brown Skin Models vaudeville show, renowned for decades for its beautiful chorus dancers, who are featured in three routines, including a mock-striptease in which Dorothy Lee is revealed in a scanty 2-piece. At least three of Miller’s performers, including Willie “Ash Can” Jones, have uncredited background parts in a club scene. After World War II, Miller’s was one of the last and certainly best known of the Black cast vaudeville shows, still playing one-nighters in the South and East. They had played Greenville and John Warner’s Plaza Theater at least twice a year since the war. The primary on-screen band, Don Dunning and his Orchestra, was also with Miller’s show, but whether any of their music is included is not clear. Several Rhythm Vets said that parts of the soundtrack did not sound like them. On screen, Winstead’s band appears to be backing up the Grand Finale performers; the Rhythm Vets all agree that’s them playing for the dancers.

It still seems possible that Miller’s and Winstead’s shows were working together when “Pitch” was made, which makes designating some of the acts as belonging to the cast of one show or the other somewhat problematic.

William Earl leaps, in the “Grand Finale”

The Billy Cornell Girls, who were the chorus dancers from Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels, included Rosa Burrell, vocalist and fire dancer, who was prone to drink, said Mattie Sloan, and one night fell over backwards as she arose with her flaming torch and nearly burned down their tent. William Earl, the senior dancer featured (but not credited) in the “Grand Finale,” was also likely with Winstead’s at the time of the filming. “He was old,” said Sloan, “I mean he was really old when he joined the show.” Unfortunately, she could not identify the other eccentric dancers, though she singled out a couple of Cornell’s chorus dancers whose names she recalled.

Bassist Charles Woods got his name in the credits with the Rhythm Vets because he had booked the gig with John Warner to make the soundtrack music. None of bandsmen saw “Pitch” after it came out; for most, it was just another gig, forgotten from their long ago past until I first started contacting them in 1986. In addition to Woods, also in the soundtrack band were Jehovah Guy, drums; Carl Foster, piano; Tom Gavin, trumpet; Richard Jones, trombone; Walter Carlson and Otto Harris, trumpet; and Raymond Pettiford and Lou Donaldson, saxophones. Sylvester Mike, another soloist (and A&T student), was with the Vets.

AND THEN

Despite its great local success, “Pitch” showed in only a few Black audience theaters in the Carolinas, and Lord-Warner folded in 1949, having made only one other film, “Greenville on Parade.” John Warner went to work for local TV station WNCT, and his brother, William Lord, returned to New York, where he’d once been arrested for having a Black songwriter visit his hotel room. (One rumor about his New York life: he performed in Green Pastures in blackface on Broadway.) The Warners were originally from Washington, NC, where they grew up living above a downtown hotel that was managed by their father. Walter Warner subsequently changed his name to William Lord in a Rosicrucian ceremony after moving to New York in the early 1920s.

In 1975, Greenville musician Bill Shepherd, who fronted the locally popular rock ‘ n reggae band the Amateurs, found the forgotten reels of “Pitch.” They had migrated across the street from the Plaza with John Warner, to the Roxy Theatre, which for a brief period in the late 1940s competed with the Plaza and then supplanted it as the only theater on the Block. Warner’s Plaza Theatre had lost its local business after an incident that caused a boycott; he was a silent partner in the new Roxy, essentially continuing to profit off the neighborhood even as its residents believed their boycott was pushing the Plaza to go out of business.

Shep and a crew of locals had found the reels in the since-abandoned Roxy after they arranged to rent it from a local businessman; one of the stipulations of their rental was that they had to clean the place. A local artist got the cabon arc projector; he recalled reels of film unfurling as they were thrown Frisbee-like in the theater. Shep rescued several reels–in addition to multiple copies of “Pitch,” there was a rough cut of early 1950s locally shot ads of Black-owned businesses on the Block and Albemarle Avenue–and kept them in a box in his big rambling house on Albemarle Avenue, across the street, actually, from one of the businesses filmed by Warner for those ads. Shep hosted weekly pot luck dinners at his home where usually either his band or another local favorite, the Lemon Sisters and Rutabaga Brothers, would practice, and the reels had wound up in a box in a closet in that house. One Sunday evening during one of those rehearsals / pot luck dinners, he showed me the boxes of film in his closet and agreed to let me take them and see what I could find out about them. I had not heard of nitrate film, film preservation, Black cast film, traveling Black cast minstrel shows, or university archives. But I called ECU’s library and got transferred to Don Lennon, director of special collections, who said he’d be glad to look at the film and that I should bring it on over.

So in the special collections reading room, we began unspooling the film to look at the credits. He noted the potential trouble its nitrate stock presented, and began reading the titles and credits aloud as we stretched out more and more film. I was writing down whatever he read from the film, and when we got to Beatrice Atkinson in the credits, Don said, ‘Hmmm, there’s a Bea Atkinson works in the library here, I wonder–‘ So he put the film down and went to his office and called her. At first I heard just his end of it, and he was saying to this Ms. Atkinson, ‘What do you know about this movie, “Pitch a boogie Woogie”? and I started to hear her over the phone and could tell that she was getting indignant that he was implying that she’d lost a film that had been shipped to the library. So he repeated the name again, Pitch a Boogie Woogie, a little more emphatically, and she insisted that if she’d had the film, it had gone through the proper channels and she didn’t know what had happened to it, thatshe’d never lost anything. So after she finished her defense, Don just started reading the names of cast members again, Tom Foreman, Herman Forbes and when he said Beatrice Atkinson, he paused, and then I could hear her loudly over the phone saying ‘Oh, my God, don’t tell me you have found that thing! Oh my God!’ From there, it was a short walk down the hall to meet Bea for the first time, an absolutely delightful lady, warm and charming who also knew other locals in the cast, and how to get in touch with them.

It was fortunate that the American Film Institute was also involved at that time in a program to try to rescue Black audience film, and AFI restored “Pitch” from its original 35 mm nitrate in 1985. Especially difficult was the soundtrack, which had been gummed up over the years. In my memory, “Pitch” was in two reels and I sent several of these–all I had–to AFI; there are a couple of places where I wonder if a splice might have been made in the wrong place. After restoration, the original nitrate film was put into storage in a vault in Colorado. Two reference prints exist, one in Durham in the Tom Whiteside Collection, and the other at ECU’s Special Collections in Joyner Library. They’re on 16 mm safety film, so some of the tap dancers’ feet get chopped off. The version shown in the WUNC-TV documentary Boogie in Black and White is from the 35 mm print, which ECU also has.

Shep and I eventually disagreed on the best path forward for “Pitch” and agreed on a price to transfer ownership of the reels from him to me.

On February 8, 1988, “Pitch a Boogie Woogie” re-premiered before 500 fans in what was also its first showing to an integrated public audience. Highlighting the evening was a reunion jam with the Rhythm Vets.

That event, and the process of producing it, made possible for me a career teaching English at ECU, although if not for a reception on the Sunday afternoon after that re-premiere, my career would have been elsewhere. I was hired at ECU in 1981 on a series of one-year contracts as a lecturer, teaching primarily freshman composition. The position could be renewed after three years for three additional one year contracts, offered at the pleasure of the chair. I spent much of 1984 and 1985 researching “Pitch” and then 1986 putting together the re-premiere program and an accompanying photography show, “Boogie in Black and White: Scenes from a Dream,” at the Greenville Museum of Art. All but final arrangements were in place when our department chair, Bill Bloodworth, called me into his office during the exam period, December 1986, for what I thought would be an update on these arrangements. Instead, that meeting was short and to the point: It was in my best interest that ECU not renew my contract after the current academic year ended in May 1987.

So at that Sunday reception, given by ECU Chancellor James Howell and his wife, Gladys, in their lovely residence across the street from campus, several guests (I know of four) made my career by asking Chancellor Howell how the university was allowing me to get away. Howell smiled at each questioner and told them each that he didn’t know but would find out. The next morning, Bloodworth called me in to his office to say that a contract for the following year’s employment was in the works. As those annual contracts were renewed, College of Arts and Sciences Dean Keats Sparrow eventually asked me to begin for ECU a literary magazine, citing as evidence of his faith in my ability to do such a thing the way I had managed to make such a noteworthy story out of “Pitch.”

Bill Bloodworth’s office also was scene to one of my most cringe-worthy moments in a 37-year career at ECU when he subsequently called me in to say that at a deans & chairs meeting to plan an upcoming visit to campus by Alex Haley, for whom a reception would be held at the Chancellor’s house, of course, it had been remarked upon that all those in the room were White. Of obvious import was to have some Black guests at this reception, and given that there were so few employed by ECU in non-custodial positions, the topic had turned to inviting noteworthy Blacks from the community. So Bloodworth beamed as he told me of how he had told the deans & chairs abotu his colleague that knew lots of Black people in town. And would I please make up a list of 10 or 12 of the most respectable.

In 1987, virtually every Sunday daily newspaper in the state ran feature stories on “Pitch,” how it was lost and found; the UNC-TV documentary showed throughout the United States–although never picked up as a PBS feature, it was offered to PBS affiliates and eventually showed in at least 25 states, more times on WBT-Boston and SC-ETV than on UNC-TV. My research agenda then led from “Pitch” to U.S. Navy B-1 and then to the African-American Navy bands of World War II ,to Mose McQuitty and the neglected role of African-Americans on circus bands and shows, and other projects–farther and farther away from “Pitch a Boogie Woogie.”

Years ago, I donated to ECU the reel of Warner’s advertisements, a documentary Warner made for WNCT-TV on Hurricane Helene in 1957 given to me by Mac Nicholson, and the Warner-relevant papers that his attorney, Sam Underwood, gave to me. After I retired from ECU, I returned to this history of “Pitch,” the completion of which had been delayed for two primary reasons (and several secondary ones). First, one of the local stars wished very much not to be associated with “Pitch,” so I refrained from talking about it locally; then, when I talked about it (and wrote a couple of pieces about it) nationally, it became clear that its use of Blackface was going to get in the way, as would my own Whiteness. The scope of my research into this complicated and fascinating world, behind a veil that few are comfortable with lifting, moved towards more national subjects that were dense enough to talk about while avoiding for the most part any intersections with Blackface. And in the process, I found a few scholars like Henry Sampson, Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff who likewise saw in this world much worth noting. For me, it became increasingly personal, as I met more and more of the now elderly African Americans who had worked for shows like Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels and Irvin C. Miller’s Brown Skin Models. It was really those folks, who let me into their living rooms and endured my sometimes ignorant questions, that interested me most, how they had enjoyed working the Jim Crow South, despite the conditions and events they’d describe. Generally these performers were about the ages of my own parents, and interviews and visits with so many actors, singers, and musicians helped me to better understand the limits and advantages my own growing up White in a Jim Crow world. It was a side-benefit that, in order to make their lives and stories more academically “worthwhile,” it was necessary to find (and sometimes correct) contexts–which this history attempts to do.

Bill Myers (L) and Sam Lathan. Wilson Daily News.

Little Charlie Morton, feature dancer on Silas Green from New Orleans in the 1930s, and Kate Abraham, feature dancer on that show in the late 1920s, were among the last of the interviews I did, back in the early 2000s, and after Dooky Chase died, I was pretty sure that Lou Donaldson was about the last person who still recalled these old tent show days. So one of my great surprises in recent months is to have encountered two extraordinary musicians, Sam Lathan and Bill Myers, both in their 90s and living in Wilson, both having played in the Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels band, bringing now to nearly 50 the number of African-American performers I’ve interviewed whose entertainment careers extend back to the late 1910s, into the 1950s–and in the case of Lathan and Myers performing with the Monitors, into the 2020s.

I’ve now sold my “Pitch” files to ECU, donating back to the library and its Rhem-Schwartzmann Prize for Student Research fund the university’s payment.

I also donated a box of VHS and Beta raw interviews from which the documentary Boogie in Black and White was built to the Southern Historical Collection at UNC-CH where they have become part of the Susan Massengale papers. You can watch most of them if you’re on campus at Chapel Hill. The remainder of those interviews and other original source materials from that research and production are now at Special Collections at East Carolina University, where they are being processed.

–July 26, 2024

Elizabeth took this picture at the “Pitch” exhibit that was part of the North Carolina Museum of History’s 2015 show Starring North Carolina.