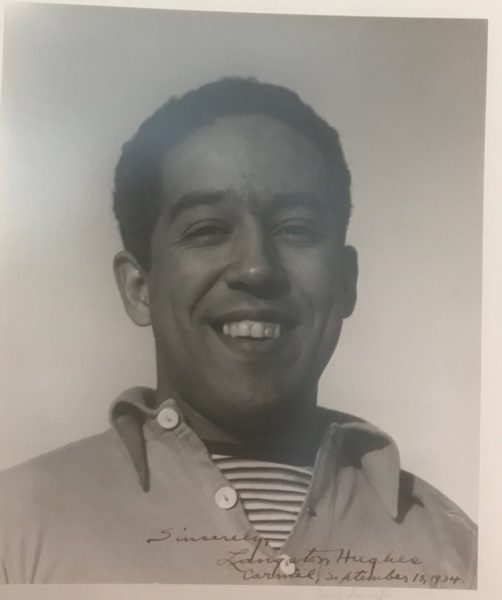

Langston Hughes in Reno

an annotated timeline based on Hughes’ 1934 daybook

I had always wanted to see Reno so, being near the Cali-Nev border, I decided to go there.

–Langston Hughes, I Wonder as I Wander

Langston Hughes’ explanation of how he came to Reno is simplistic, and none of his biographers seems to have bought it. He clearly wanted–and needed–an extended retreat from the distractions of his active social life and political activism in Carmel in a place where he could live cheaply, but more immediately, he needed to feel safe from the vigilantes who’d threatened him in Carmel. He hoped to find both in Reno, which he enjoyed so much on his first scouting trip that he began making plans once he returned to California for an extended Reno stay. The untimely death of his father, in Mexico, ended his Reno days prematurely and he never returned.

Two of his best short stories, “Slice ’em Down” and “On the Road,” were directly influenced by his time in Reno. Both use Reno settings and characters, “Slice ’em Down” more so in its entirety. Hughes enjoyed gambling and nightclubs wherever he could find the opportunities, and he loved mixing with regular folks, as opposed to literati and the fine folks of high society. He walked about the city, exploring its hobo camps and, no doubt, the Stockade. It’s easy to read between the lines of his Reno daybook that he had a good time in the city.

“Slice ’em Down” even employs Hughes’ own “late October evening” into the club scene that would likely have been based on the “colored club” he’s introduced to during his first week in Reno; he notes going there again on the first night he’s back in town, after his scouting visit.

Rampersad suggests Hughes went to Reno anonymously on a whim. It was not unusual for him to register in rooming houses and hotels as James Hughes, his father’s name. But it was also Langston’s first name. It also seems clear that Hughes knew sort of what to expect in Reno, and he also seems to have had enough contacts and references from those contacts that anonymity would have been impossible, even had he wanted it.

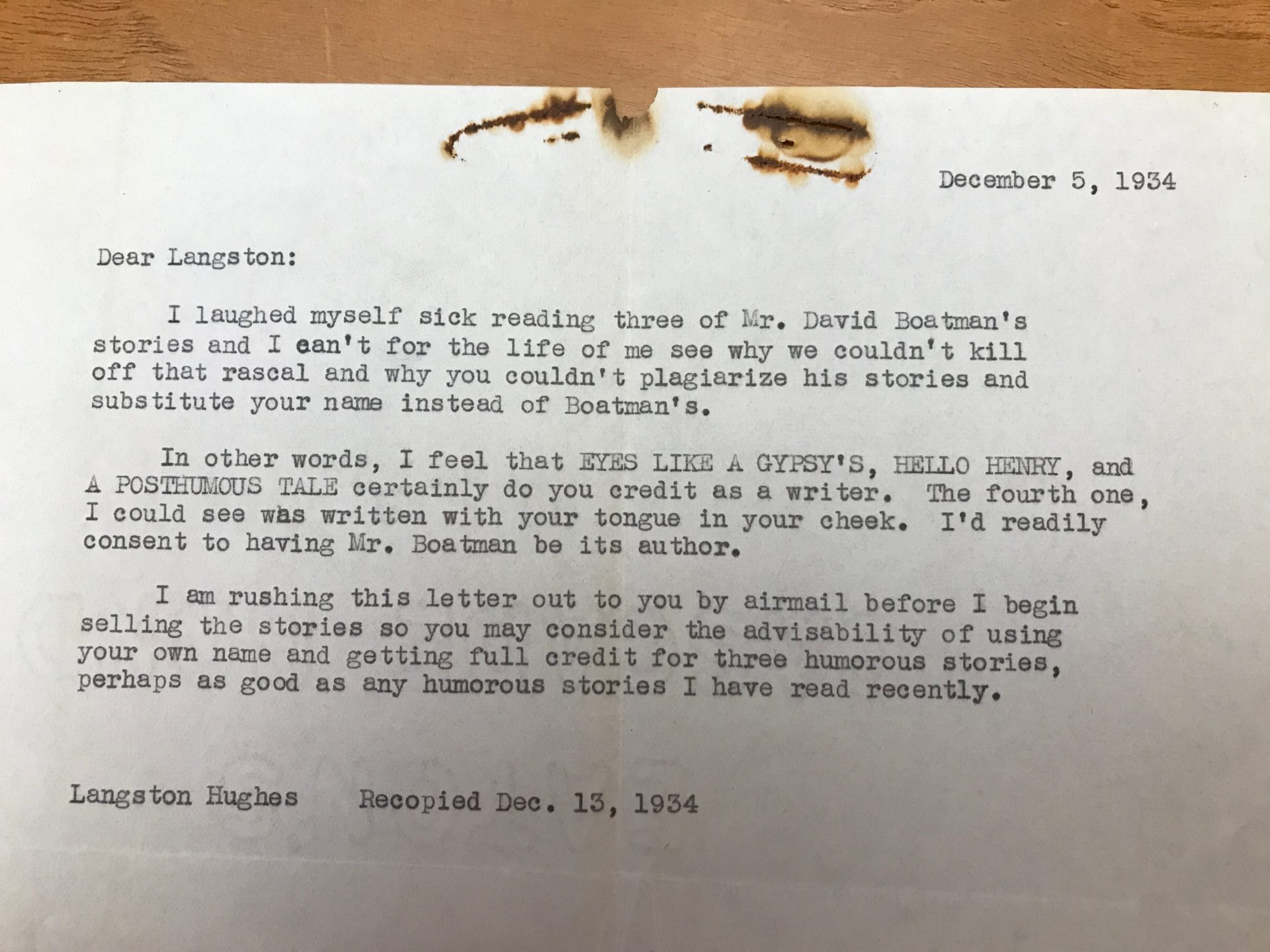

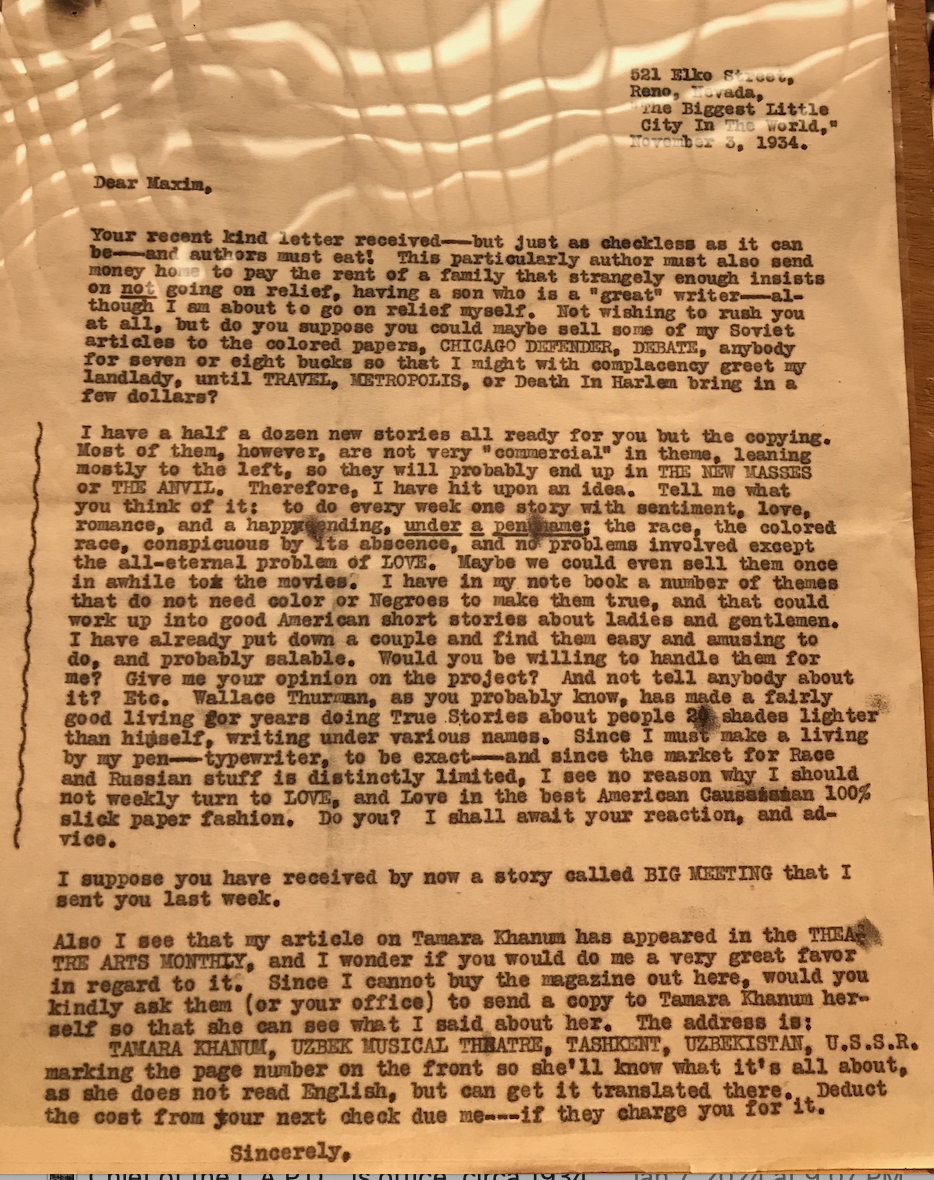

Hughes also completed perhaps as many as a dozen stories while in Reno; those he wrote as “Negro stories” were based on ideas and situations that preceded his Reno days. The idea for his “White stories,” using the pen name David Boatman seems to have originated and died while he was in Reno. Laurie Leach says there are five White stories but I can find evidence of only four. None have been published.

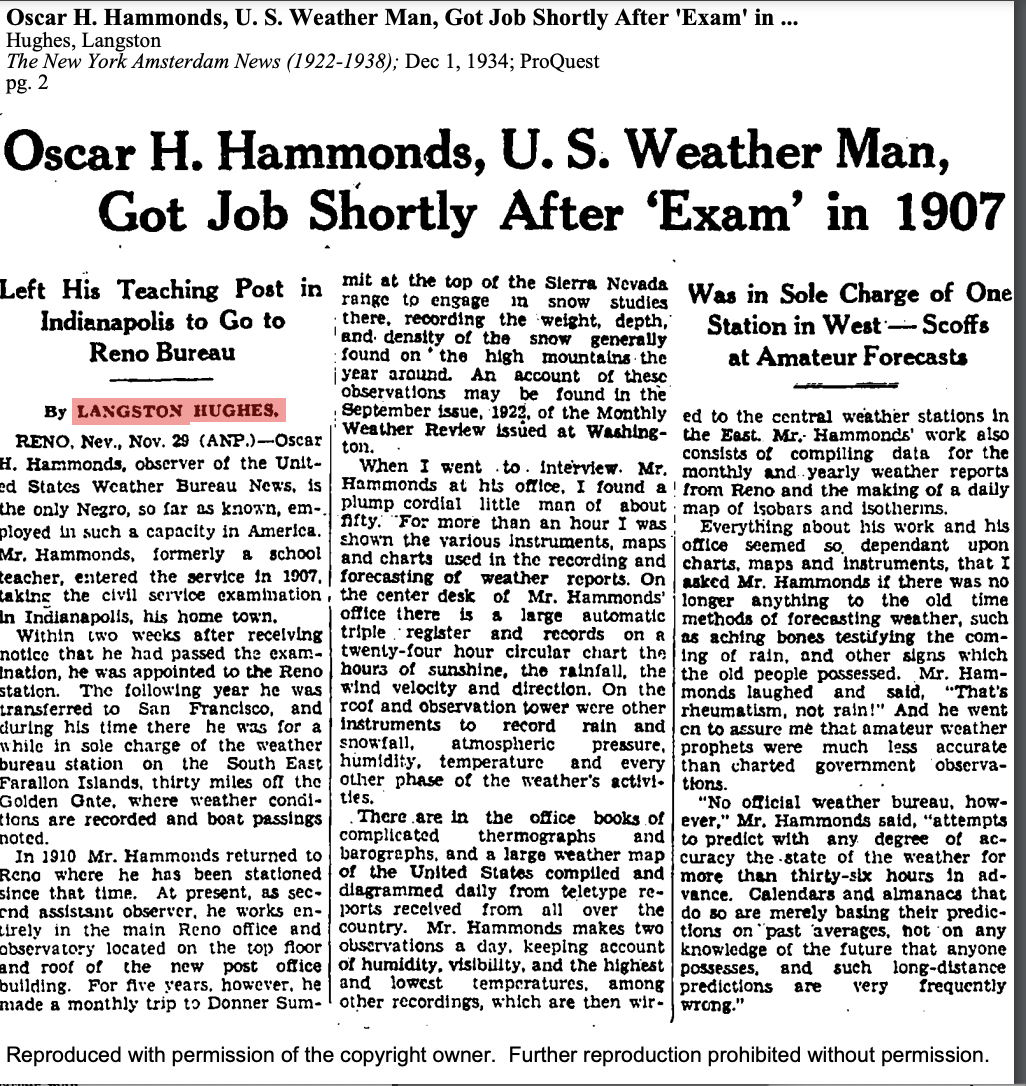

Two principal Reno characters easy to identify are his landlady, Helen Hubbard, and Oscar Hammonds, the weatherman he profiled for the Chicago Defender near the end of his Reno days. Hubbard and Hammonds share several connections, principally that of Bethel AME Church but also in their appearances together, usually with their spouses, (until she divorces hers) in other society news. They would have inhabited a different world from the nightlife Hughes enjoyed at gambling joints and clubs like the one which inspired “Slice Him Down.”

September 1934

Sept 1 [Saturday]

We leave for Echo Lake. Stop at Cathedral Oaks ? to hear Barabas read for Tarah’s birthday. Dinner at the Cats / Cato ?

Sept 2

To Ernestine Ball’s on Echo Lake. Slept under the stars. Can feel the altitude 7620.

Truckee train station 1940. Truckee-Donner Historical Society.

Sept 3

Rowed and swam in lake. Went to see [BLANK SPACE ] ] getting divorce in Nevada. On to Truckee.

Sept 4

Noel goes to SF. I leave on 5:55 for Reno. Stop at Mrs. Hubard [sic], 521 Elko Street.

• Helen Hubbard, Hughes’ landlady while he called Reno home, had been active in Reno’s Black social and religious activities since marrying Camilus Hubbard in April 1923; the Chicago Defender identified her as Helen Taylor of Kansas City, and he of Los Angeles. They took up residence on University Avenue and counted in their social circle Oscar H. Hammonds and his wife. The Hubbards hosted a bridge party “till a late hour” in January 1924, followed by a “dainty luncheon.” She was on the community sick list for most of March 1924 but by April was convalescing and with the Hammonds and others enjoyed a surprise birthday party for W.H. Nelson given by his wife: music, dancing, games, and whist prizes. During that Spring, Helen Hubbard also hosted an after-church party to honor a couple visiting from Sacramento and gave a farewell party for Mr. & Mrs. George Jones, who were moving to California. The Hubbards and Hammonds enjoyed another “dainty luncheon” after “dancing till wee small hours” in May. In June, the two couples were part of large crowd who gathered at the AME reception hall, decorated with South American roses, to honor of Mrs. S.A. Wright, past matron and grand prelate of the Order of Eastern Stars, California. Mrs. W.H. Nelson, soloist, was accompanied by Mrs. James Daniels on piano for a recital that was followed by dancing and games until late, and then “an elaborate luncheon.” She had a birthday party for herself on October 20, with dancing, progressive whist, and at midnight “an elaborate 3-course luncheon.” The Hammonds, of course, were among the two dozen guests.

Camilus M. Hubbard, a porter at the Overland Hotel, was shot in the neck “by a Southern white man” in August 1922; the local NAACP, organized in 1919, became part of the prosecution, and J.S. Parks was eventually convicted of shooting with intent to kill in the incident, which had involved an allegedly drunken Parks losing the key to his hotel room.

Helen Hubbard sued Camilus for divorce in 1926 [“Suits Filed” Reno Gazette May 1, 1926: 8]; he appears to have remained at their 309 University Avenue residence; she moved to 521 Elko Street where she began operating a boarding house and is identified as a maid in the Reno City Directory 1932. It was news that she hosted the “prominent beautician of Los Angeles, Miss Carroll” that year..

She was elected secretary of the Colored Women’s Unity Club in 1927 (“Election of Officers,” Nevada State-Journal 13 Feb. 1927)

The Chicago Defender has no regular Reno correspondent from November 1924 – February 1930, but at that point, Helen Hubbard resumes her role as an often mentioned participant in Reno’s Black cultural life. Usually identified as “Mrs. Helen Hubbard,” she and the Hammonds attend lots of parties and take the occasional excursion to Sacramento.

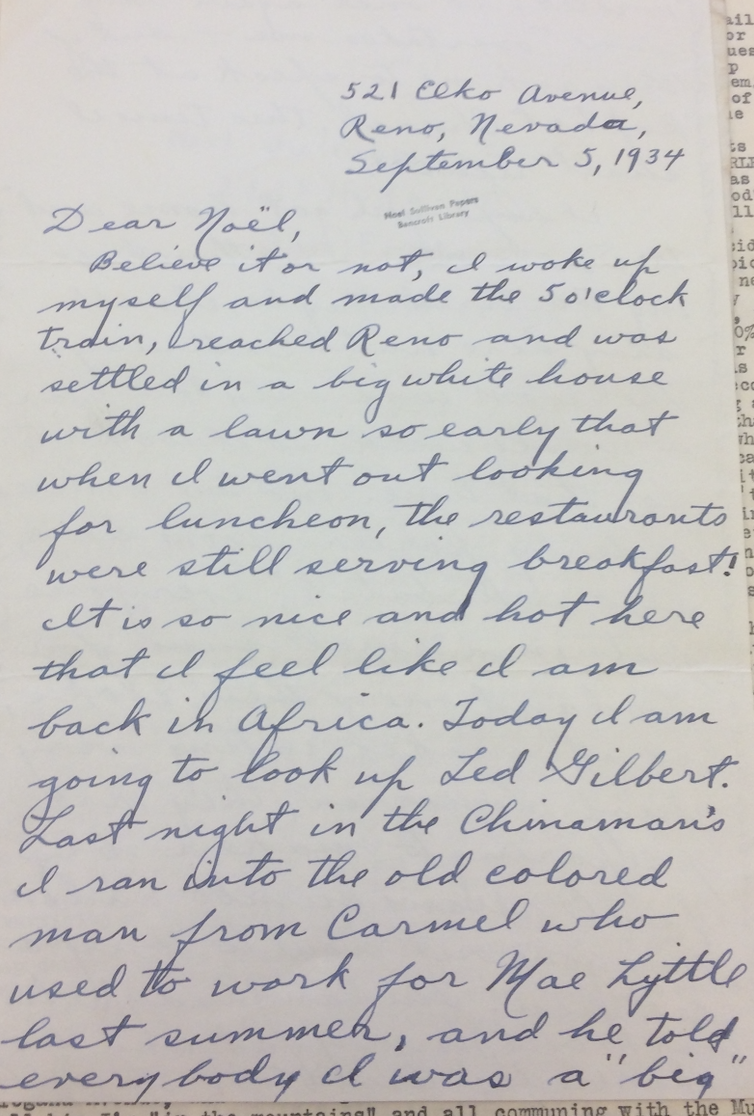

Sept 5

Several fellows, porters, etc, batch here. I go in with them on board.

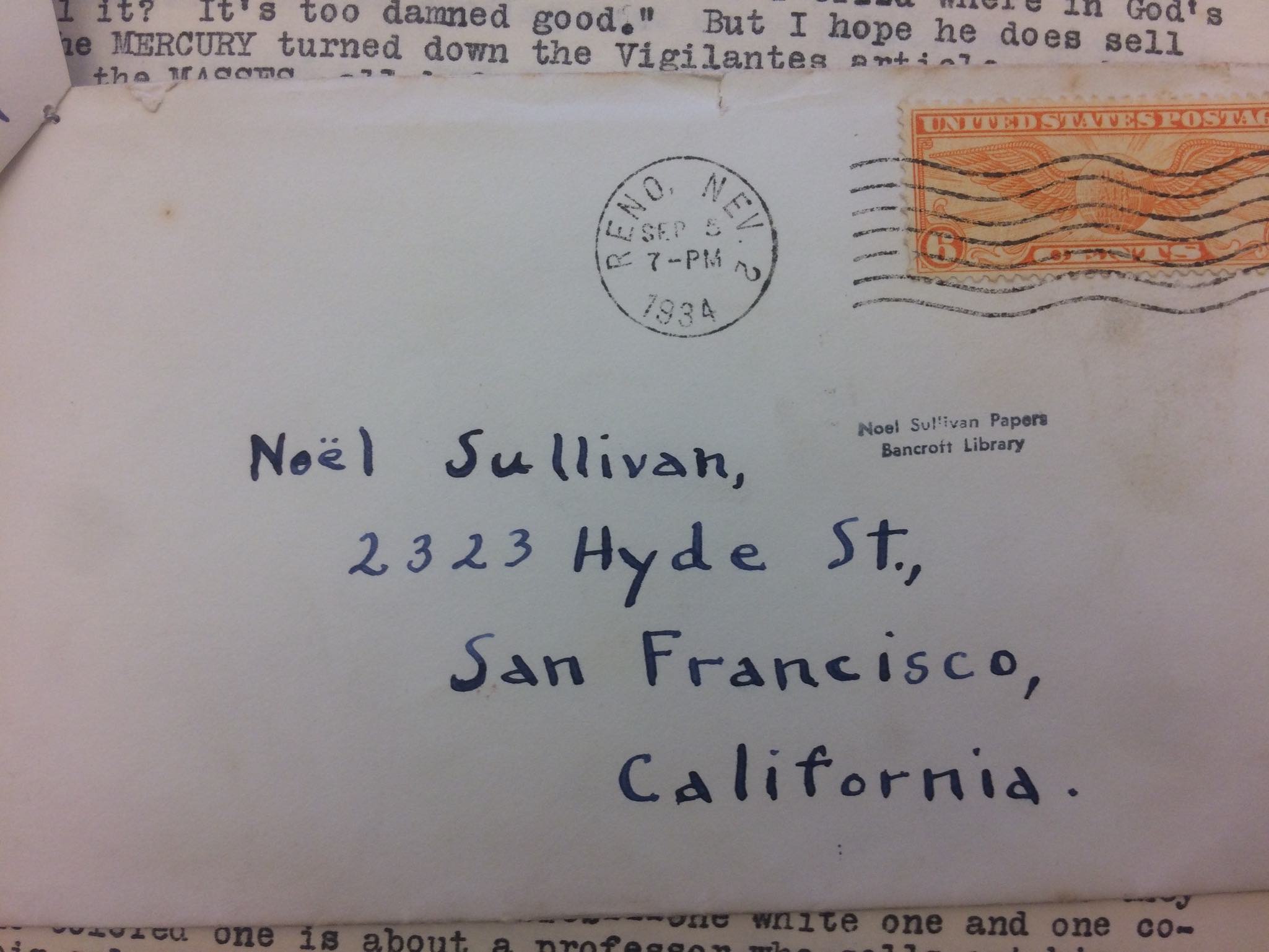

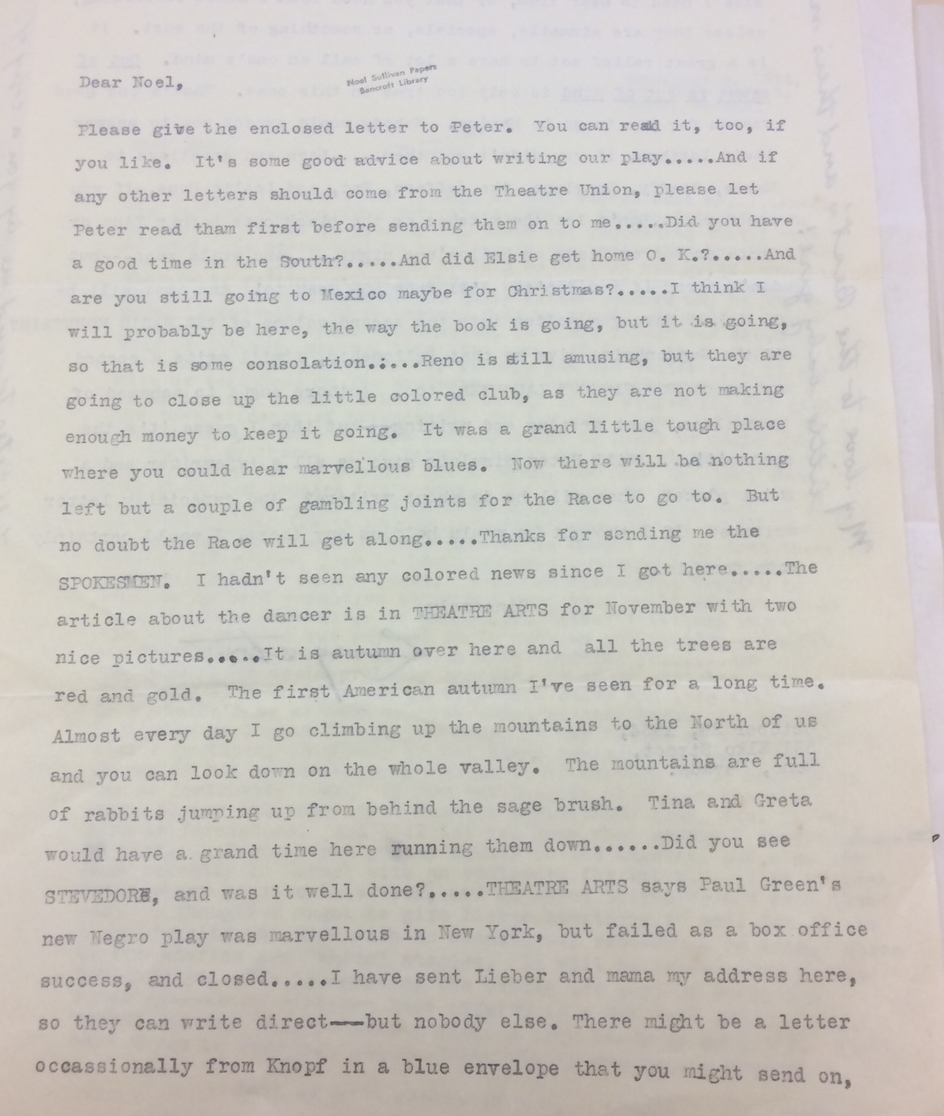

• Hughes’ letter to Noel Sullivan, written soon after his Reno arrival, describes the boarding house he’ll use as a home address for nine days and again for six weeks in October and November.

Sept 6

Got in touch with Ted Gilbert at the old Nixon House. Won 2.00 at Chinaman’s

• The Nixon Opera House, built in 1907, burned in 1992. It’s not clear what role Gilbert had at the Nixon, or when or how often Hughes visited there.

Sept 7

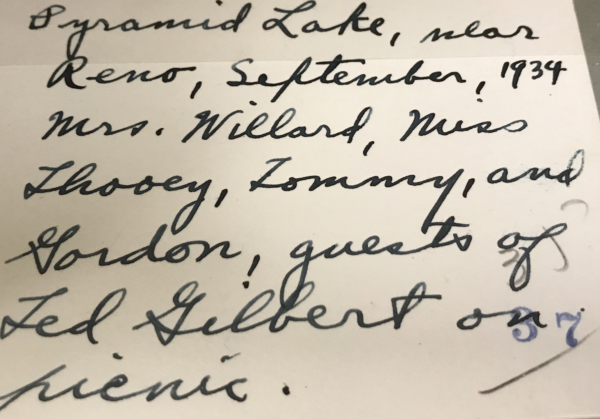

Had tea with Mr. Gilbert, Mrs. Willard (Union Trust Co.) and Miss Toohey of Washington. Also C—?

• 1933 & 1935 Reno City Directories, using “CD” to indicate “colored,” has Martin & Kath. Toohey at 545 University Avenue, as manager(s) of Butler Apartments. 1935 City Directory lists John M. Willard at 142 Virginia Avenue and Thomas H. WIllard, a cook, at 29 E. Plaza, neither with a wife.

Sept 8

Went to Pyramid Lake with same party from picnic, Back to lose 3.00 at Chinaman’s.

Photo by Langston Hughes. Bancroft

Sept 9

Lost 3 bucks at the Chinaman’s. To colored club with Garner.

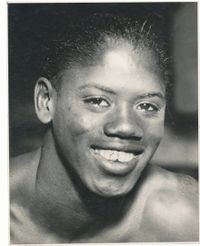

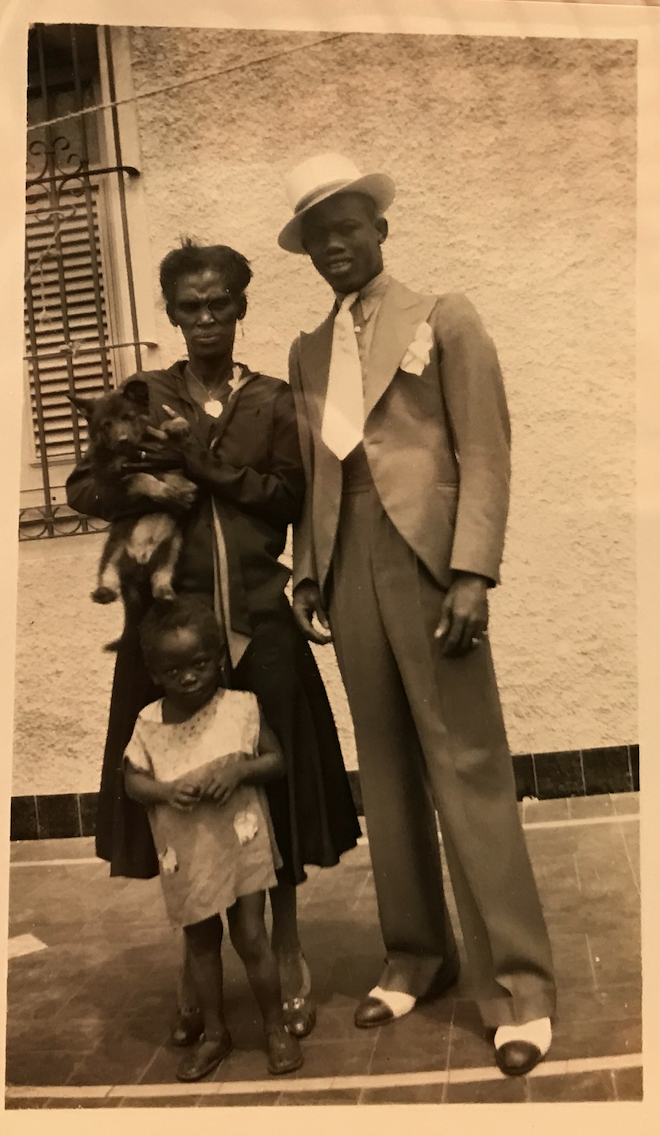

Kid Chocolate

Sept 10

To the gym with Chocolate and Wilber. Kept time for the fighters.

• Kid Chocolate, who was one of the most popular Black boxers of his day, had neared the end of his impressive career by the time Hughes kept time for him at the Chestnut Street Gym, 246 Chestnut Street [now Arlington & the corner of Arlington & Commercial Row.]

In August and September 1934, the gym hosted boxing and occasional wrestling matches on Friday nights. Kid Chocolate fought to draws twice in August; prior to his August 25 fight, the Nevada State-Journal notes that he’s “formerly of Reno.”

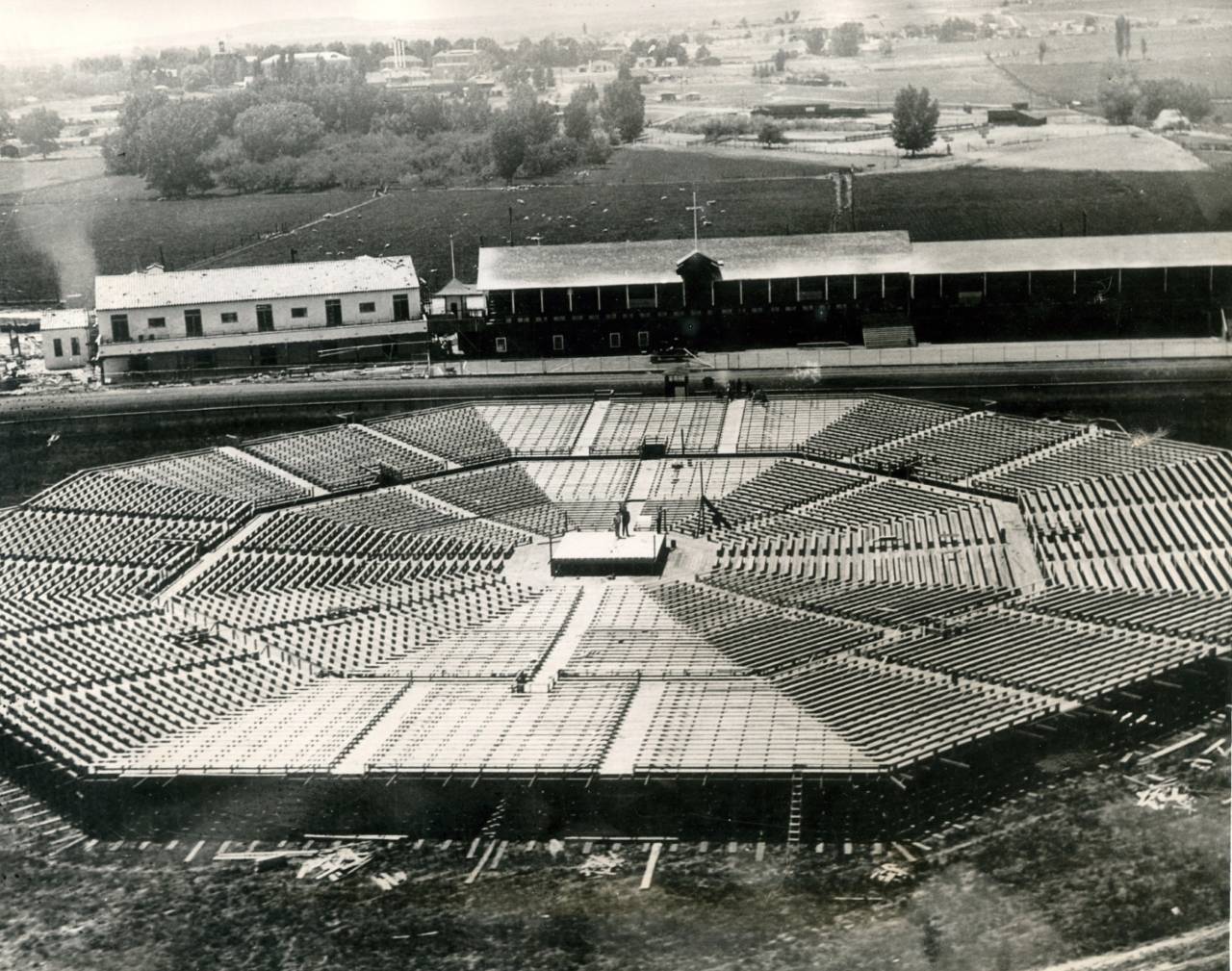

Race Track Arena, Reno, hosted boxing bouts on Labor Day 1934. Boxrec.com

In 1934, open-air fights were also staged at the Reno Race Track on the grounds of what has become the Washoe County Fairground, where Jack Dempsey promoted a Max Baer fight in 1931.

Chocolate fought 11 sanctioned bouts in 1934, 8 wins, 2 losses, and a draw. When Hughes kept time for him, he would have been training for a November fight that he would win by knockout in New York.

Chocolate, whose real name was Eligio Sardinias Montalvo, learned to box by studying film of three fights, including Jack Johnson’s win over Jim Jefferies on July 4, 1910, the biggest sporting event ever staged in Reno.

Also known as the Cuban Bon Bon, Chocolate was noted in the press for his extravagant nightlife as well as for his boxing skills. He won his first 51 bouts; some boxing historians believe his final record would have been much better, as good as 98-1, had he not been deprived of victories by prejudiced judges.

During the 1930s, boxing was the only major sport open to Black athletes, though Blacks often fought on under-cards against other Black fighters; championship bouts against White opponents were especially difficult to arrange. Chocolate was both a welterweight and light-weight champion.

Hughes met up with Chocolate and his mother and took their photos while visiting Cuba in 1927, near the beginning of his professional career, and he had plans for writing a screenplay based on Chocolate’s life and career.

Any screenplay based on Hughes in Reno would certainly include a scene or two of Kid Chocolate showing Hughes the city’s nightlife.

Sept 11

To Virginia City with Gordon, tour the old gold mines Crystal bar and opera house.

Sept 12

Everyone came to see me off at the airport. Swell flight over the mountains and into the sunset.

• This was Hughes’ first time flying. Hubbard Airport was established in 1927; Charles Lindberg’s landing there helped publicize that it was open for business. (Skorupa, SUsan. 29 Jne 2003. Reno Gazzette-Journal 1-2B.) Amelia Earhart’s 1931 stop en route to Sacramento in 1931 preceded a 3-crash return trip back East (Cafferata, Patty. Reno Gazette-Journal, 10 Jine 2014: 3D)

[BACK in SF / CARMEL]

Sept 13

Telephoned Talla Mae, Dorothy, Gladys, Matt. Down to Carmel with Noel.

Sept 14

Spent the afternoon on beach with Marie, Rhys, Noel, Ella, Dan and others.

Sept 15

To Peter Pan Lodge at invitation of Mrs. Mathias to listen to Krishnamurti, amusing and abstract.

Sept 16

To Big Sur and above the fog with Douglas and Marie Smart, Constance Comago.

Sept 17

Worked all day sorting and packing. Wrote letters. Sybil and Vasher Anrkeeff down again to Peter Pan to hear Krishnamurti. This time better.

Sept 19

Paul Fleegal draaws my portrait. Dorothy Erskine comes in for dinner.

Sept 20

Up at 6 and to city. Haircut. Early to bed and to sleep.

Sept 21

Roy typed for me all day on play and new poems. Dinner at Dorothy’s.

Sept 22

Spoke on my book at Paul Elder’s Gallery. Overflow crowd. Had to speak twice. Met Lillie Kerner and William Saroyan, supper with them. Out with Talla Mae in eve.

Sept 23

Constance Kamaga took my photo. To Carmel by train to see Elsie & Ernestine.

Sept 24

Burleigh, the pianist, in for dinner with Noel, Elsie Arden and Ernestine Ball.

Sept 25

Up the Carmel Valley to dinner with Paul Flegel at rancho San Carlos. Songs in the moonlight.

Sept 26

Worked on an article “Vigilantes Knock at My Door.” Sent off poems to Lieber.

Sept 27

Found my account at bank overdraawn by 5.80. Went to see Ella and Steffy.

Sept 28

Pat off, so cooked my own dinner. Had two steaks. Noel comes from city.

Sept 29

Started a story “On the Road.” Worked on play. Got $13 check from the New Republic.

Sept 30

Up to Dr. Kocher’s for picnic with Noel and the Shorts. Read Saroyan outdoors.

October 1934

Oct 4

Very early up to city. Went to dentist and home to bed. Slept 11 hours.

Oct 5

Roy came over to type. Worked all day on letters, early to bed.

Oct 6

Letters all day. In evening to see John Pittman just back from New York and Atlanta.

Oct 7

Fan Jacksons come up from L.A. with plans to start a Negro theatre there.

Oct 8

Went to see Billy Justenias exhibit at Courvoiser. Met Albert Bender.

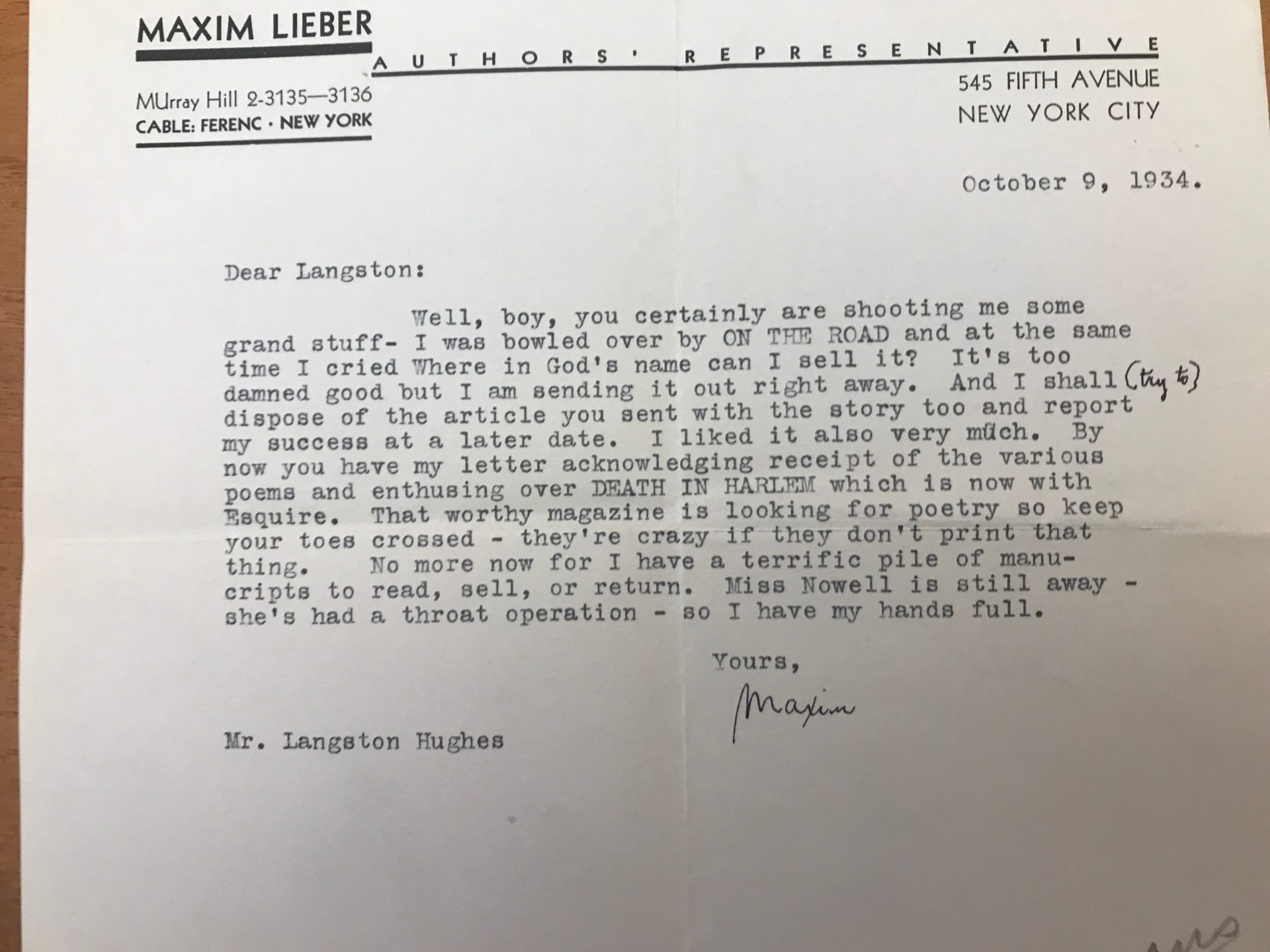

Oct 9

Worked on mail all day.

Oct 10

Went to see my proofs at Constance Kamaga’s. She gives me lovely photo of Lester, Marie Short’s maid.

Oct 11

To Berkeley with Noel to hear Ella Young’s lecture on the Gaels ? and the Tunics.

Oct 12

Wrote 18 letters. Packed. Elsie Arden leaves for New York, me for Reno.

BACK in RENO

Oct 1

Arrive Reno in early morning. Win 1.50 at Chinaman’s. To colored club at night. Swell blues and jazz.

Hughes Oct 14

To Carson City with the Dixie Quartette. Fouche; Arnette Williams, 2 more of L.A.

Oct 15 – 21 [no entries]

Oct 22

Worked on book. Went for walk. Began on story about dead wife.

Oct 23

Finished a story called “Mailbox for the Dead.” 1st draft. [also titled “Postal Box Love”]

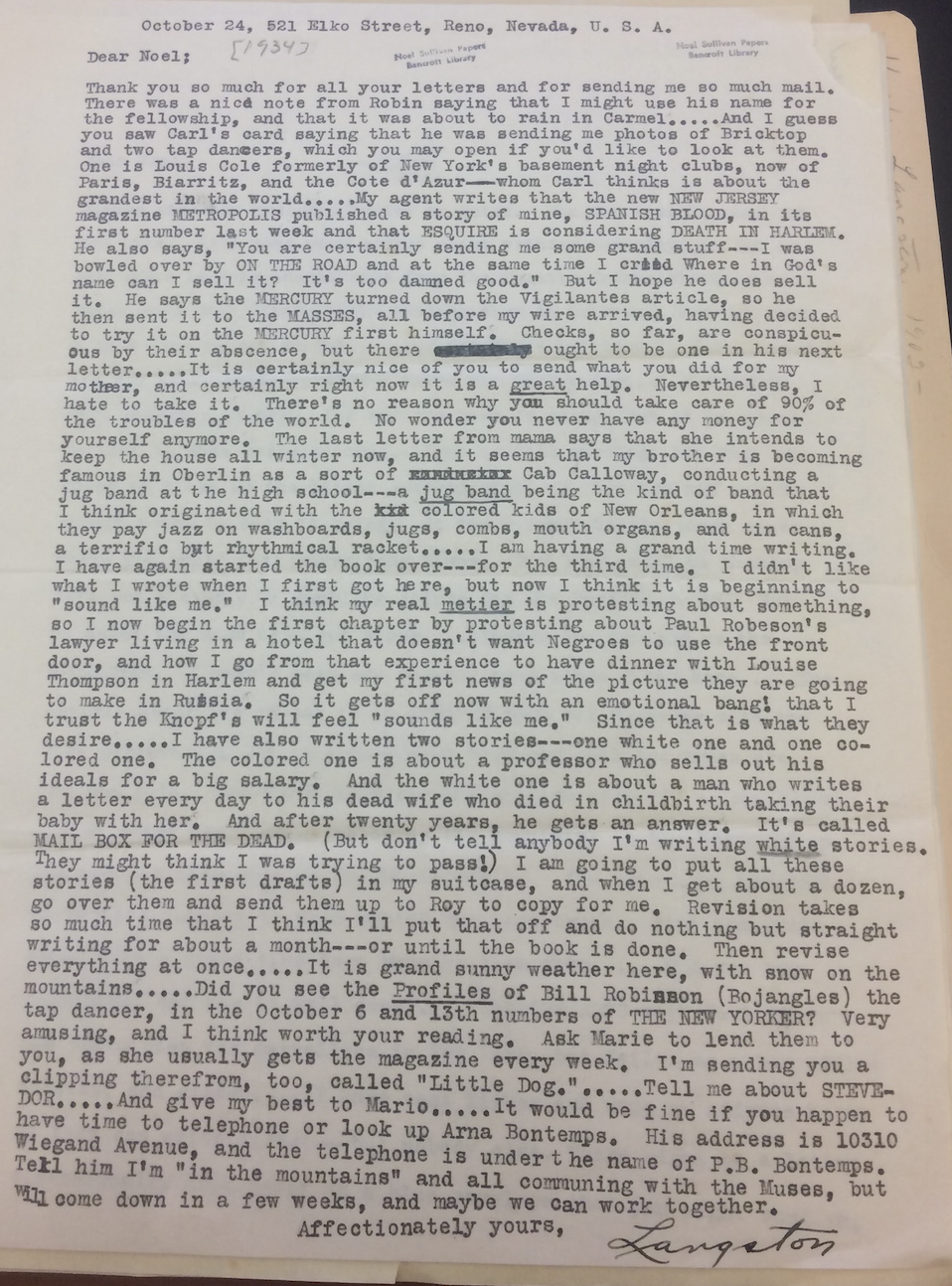

Oct 24

Went for a long walk in the mountains to the north.

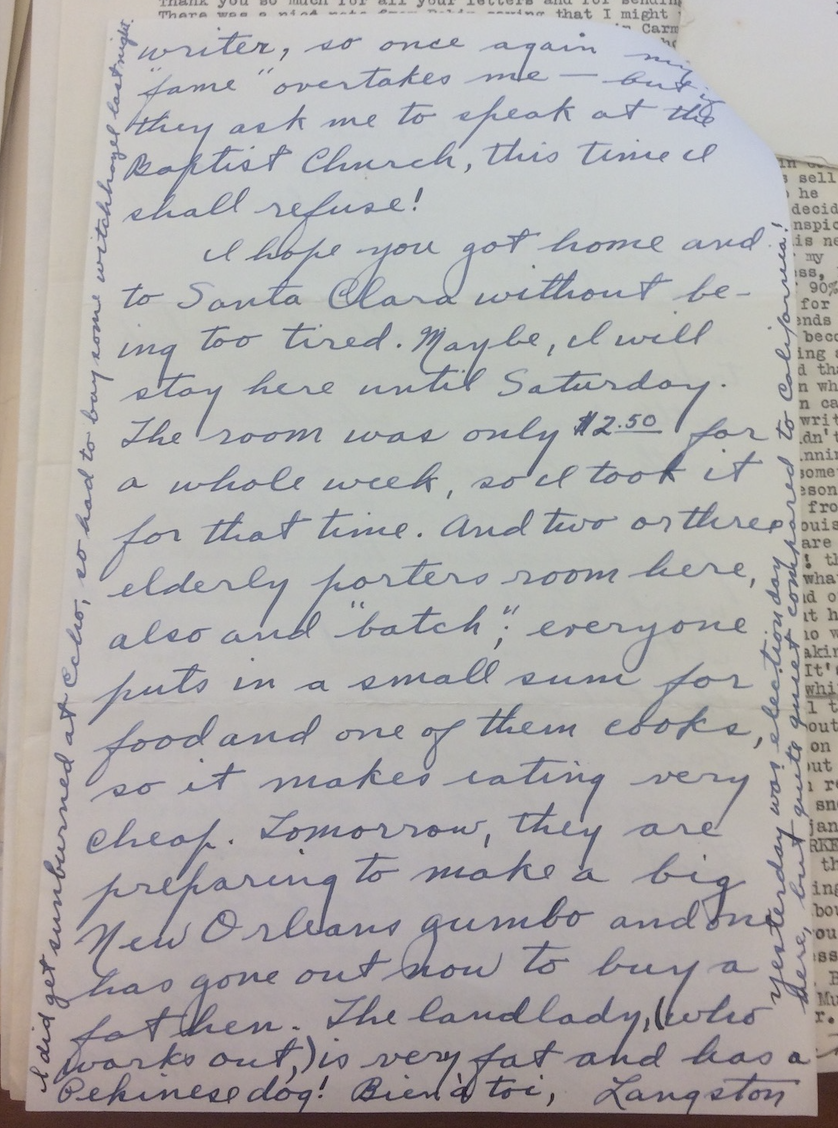

[also wrote to Noel Sullivan this letter]

Noel Sullivan Papers. Bancroft

• Maxim Lieber responded to Hughes’ submission to him of four stories by David Boatman:

Beinecke

Oct 25

Posted application to the Guggenheim’s today.

Oct 26 -0-

Oct 27 -0-

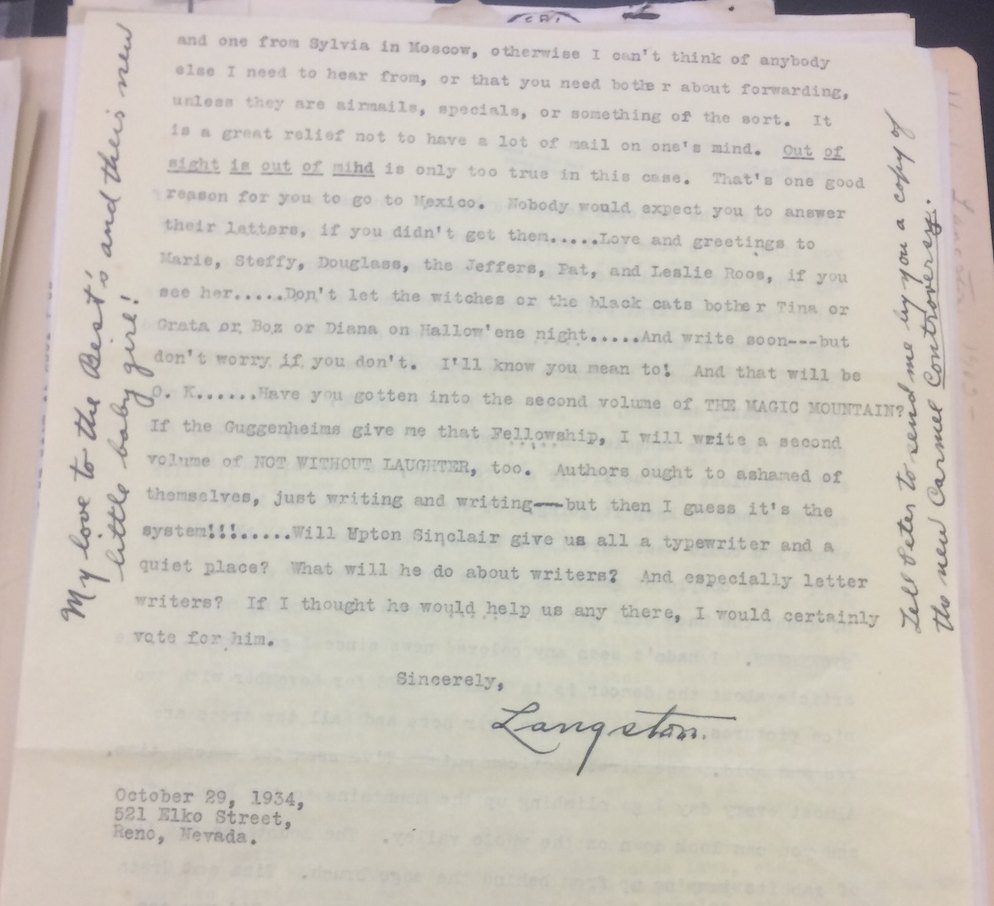

Oct 29 -0- [no entry but this letter to Noel Suillivan]

Noel Sullivan Papers, Bancroft.

November 1934

Nov 3 -0-

[No entries; he wrote this letter to Maxim Lieber]

Nov 4 -0-

Nov 5

A letter forwarded to Reno from Dolores Patino dated Oct. 22 saying my father is very ill.

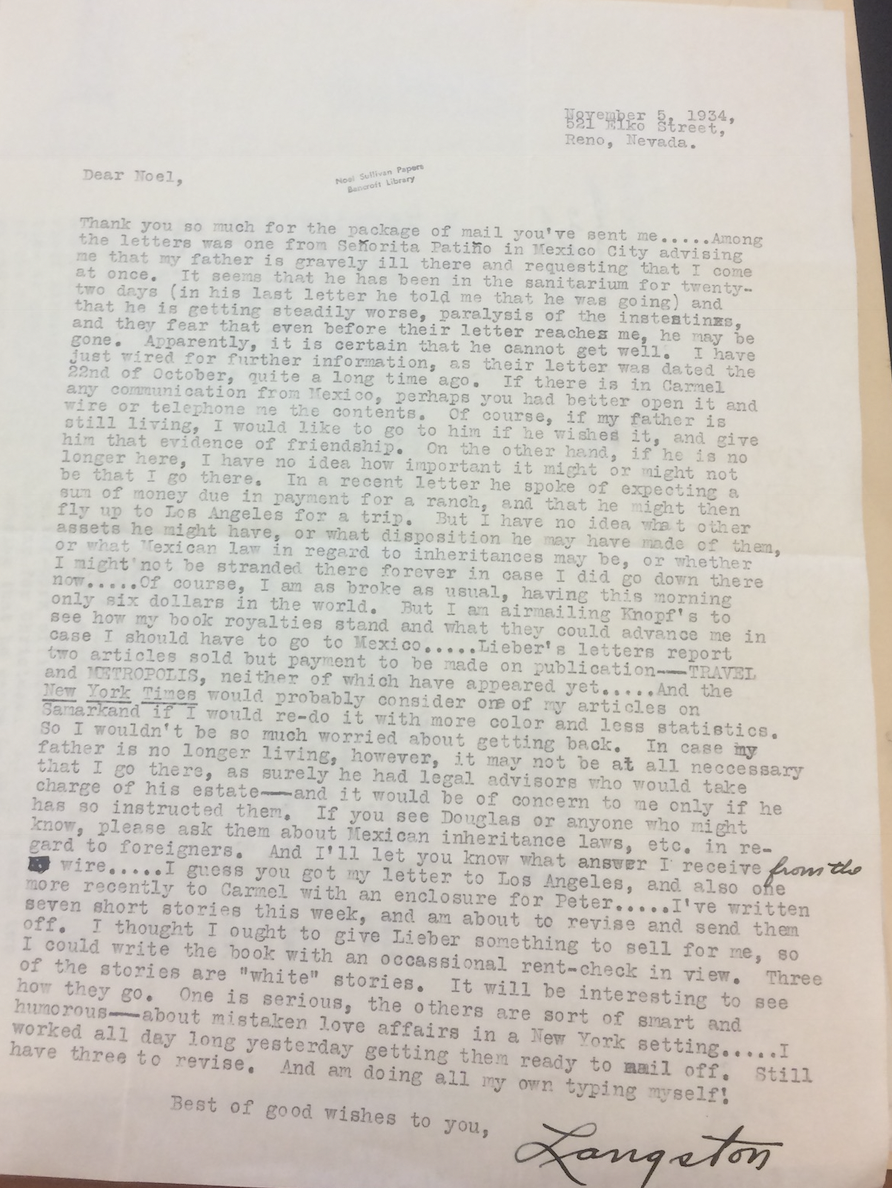

[LH wrote this letter to Noel Sullivan]

Noel Sullivan Papers, Bancroft.

Nov 6

An answer to my wire of inquiring saying that he did on October 22nd.

Nov 7

Mailed off 4 Negro stories, Professor Tailor & Steward etc. Went to see Count of Monte Cristo.

Nov 8

Won $2.50 at the Chinaman’s. Trying to raise money to go to Mexico.

Nov 9 -0-

Nov 10 -0-

Nov 11 -0-

Nov 12

Check for $100 received from Uncle John. Won $1.50 at Chinaman’s.

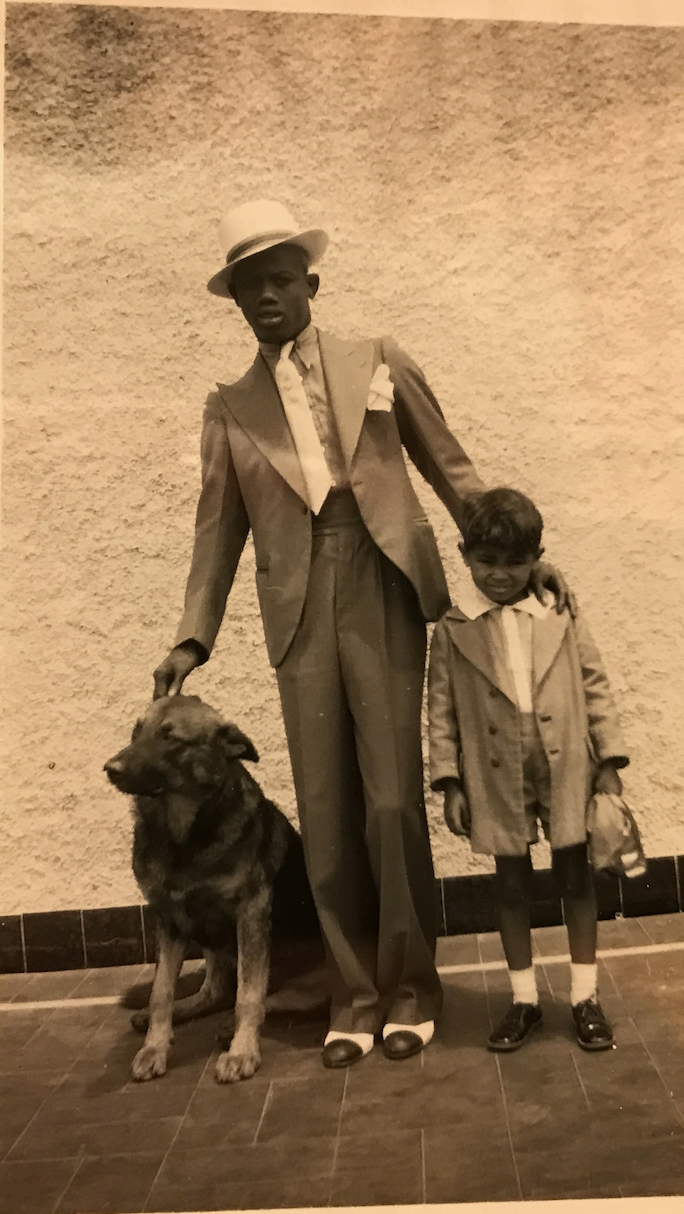

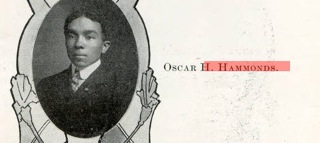

Hammonds high school portrait

Nov 13

Interviewed Oscar Hammonds, the colored weather man here.

Hughes’ profile of Hammonds was published in the Chicago Defender.

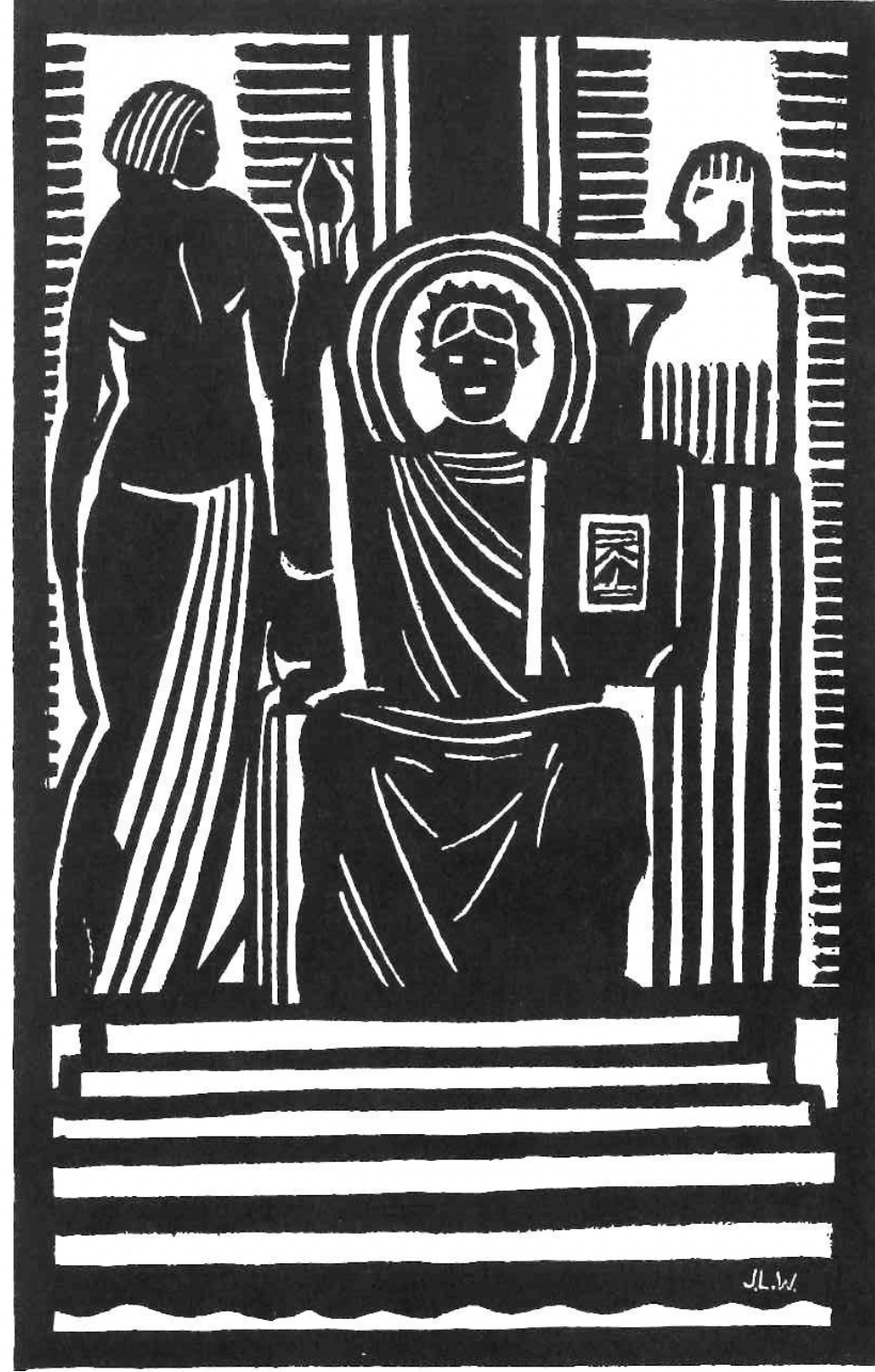

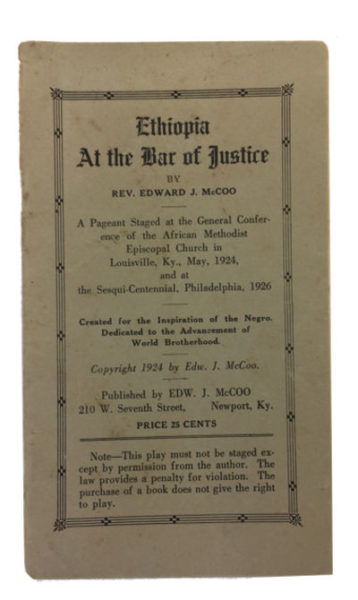

Oscar Hammonds was a prominent member of Reno’s AME Church, serving as its treasurer and an organizer of frequent special events. The church staged Ethiopia at the Bar of Justice several times in the early 1930s. Written by Edward McCoo, it was a popular play in Black communities throughout the United States and was staged by the general conference of the AME church in 1924. James Wells illustrated the concept for W.E.B. duBois’ The Crisis.

James L. Wells illustration for Ethiopia at the Bar of Justice. NYU.edu/lapis

The Reno productions were for integrated audiences and at least two of them had essentially the same cast, including Oscar Hammonds.

Oscar Hammonds is seated at center with the Reno cast of Ethiopia at the Bar of Justice

This article was widely distributed via the Associated Negro Press. The headline writer for one paper, the Norfolk New State Journal–didn’t read the story, however: “Divorce Mart Claims Only Negro Weatherman in US; ‘Discovered by Poet Hughes'”; its copy is exactly as distributed by ANP.

Oscar Hammonds was one of early Reno’s most remarkable Black citizens. He was President of the NAACP when it organized, in 1919, the first in the state of Nevada, and he was Bethel AME’s caretaker in many senses of the word for decades. In reports from Reno published in the Chicago Defender, the social activities of him and his wife, Mabel, are noted as many times as anyone’s. He helped organize the Progressive Club in 1922 (later changed to the Criterion Club) to raise funds for the church; he chaired its entertainment committee and helped organize smokers and dances, some of which featured the Hammonds Harmony Four. She helped organize the Women’s Mite Missionary society, which often met at their home, at 537 E. Scott Street. To raise funds for new church pews, the Criterions hosted Mme. Anita Patti Brown, Black Patti, in a 1923 “musical treat seldom enjoyed by the people of this city.” He was also president of the Booker Washington Forum.

As weather observer, he wrote countless summaries and predictions that were distributed throughout the western region, rarely with a byline, but if collected, his would represent a sizable body of publications.

He led the Hammonds Harmony Four that entertained frequently and starred in at least three productions of Ethiopia at the Bar of Justice. As late as 1941, he was a trustee at Bethel AME, helping to raise funds for renovations.

She and her sister, Mrs. Alberta Jones, hosted a birthday dinner for their mother, Mrs. Louise laBarriere of New Orlens, in July 1933.

Nov 16

Left tonight for Frisco. Bill Allen’s birthday, wine drinking party.