Langston Hughes in New Orleans

Langston Hughes’ most noted visit to New Orleans was in February 1932, when he met a young Margaret Walker after a poetry reading at New Orleans University.

Margaret Walker by Carl van Vechten 1941, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

“After the program,” he writes in I Wonder as I Wander, volume two of his memoirs, “a teenage girl [she was 16] came up to me and handed me a sheaf of poems, which I glanced at quickly between shaking hands and autographing books. . . I took the poems to be the usual poor output so often thrust into my hands at public gatherings. then, almost immediately, I aw that these poems showed talent, so I spent an hour after the program going over them with the girl and pointing out to her where I thought they might be improved.”

Walker would later write, “I had never met a live poet before.” She credited Hughes for encouraging her to leave the South for her education, which she did, later attending Northwestern University, like her father.

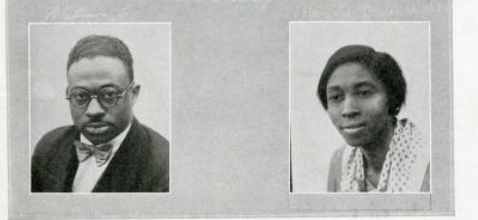

Walker’s family had moved from Birmingham to New Orleans, where her parents were teaching at New Orleans University: her father, Rev. Sigismund C. Walker, a sociology professor, and her mother, Marion Dozer Walker, a piano instructor and director of the school orchestra.

In New Orleans, Walker had graduated from Gilbert Academy, the high school associated with New Orleans University, which had been established when the city had no high schools open for Black students. Her biographer, Maryemma Graham, writes: “Instruction and encouragement at Gilbert were reinforced by what had now become common practice at home,” and she quotes Walker: “hearing my mother’s music, my sister and brother playing the piano, reading my father’s books and the trees that I watched through the bedroom windows, hearing his sermons, and trying every day to write a poem.”

Peck Hall, New Orleans University, 1928

Walker was in her sophomore year at New Orleans University when she heard the grand news that her parents would be hosting Hughes as part of a book tour he had organized to raise funds for and awareness of the Scottsboro boys. (Tulane had declined the opportunity to host Hughes; the University of North Carolina wound up being the only White university that hosted him on this long tour, but he left Chapel Hill in a hurry after his poem “Christ in Alabama” appeared on the front page of a local literary magazine and caused a stir.) The event, organized by her mother, took place on February 11 at Peck Hall on the university campus.

Walker describes the evening in an unpublished manuscript:

“I had carefully concealed my date-book with all my poems in it and three times I went through the receiving line trying to get enough courage to speak to him. The first time I could not lift my eyes. . . . Next my English teacher went to introduce me but I still lost my tongue. . . . Finally, I plunged forward again. . . . Mama who remembered why she had gone through all this work, told him I had my notebook and wouldn’t he take a look and see if they were any good. He did read my poems one after another and said they were very good. And he punctuated these remarks by echoing Miss Fluke’s words to my parents, “You really must get her out of the South.”

Rev. Sigismund C. Walker, Sr. and Marion Dozer Walker, The Tiger [New Orleans Univ. annual] 1928. archive.org

Graham summarizes the event: “The words shot through Walker like a bullet. It was a moment she had been waiting for. Hughes had not only become her model, but also the voice of authority.” Walker subsequently transferred to Northwestern University.

Hughes recalls in his memoir that his reading was at Straight College, not an uncommon mixup. New Orleans’ two Black colleges were thriving in the late 1920s but during the Depression, in 1934, New Orleans University merged with Straight College to form Dillard University.

The Louisiana Weekly reported that Hughes’ reading “taxed to capacity” the university’s auditorium, and that his “ability as a lecturer was discovered early in his reading when he opened his talk with a famous little two-verse poem, ‘All Dressed Up and Nobdoy to Call Me Sweet.'” Interviewed at the Astoria Hotel the next morning morning, his manager / chauffeur, Radcliff Lucas, said more books had been sold at New Orleans “than in any other city” on their tour, and Hughes recalled that on his last visit to New Orleans, “I could not sleep in a hotel when I was in this city four years ago.” But he seems to mis-remember the circumstances that had brought him to New Orleans: “I was working on a fruit boat for a very small salary. It was at that time I was preparing my poems and picked out New Orleans for one of my early recitals.” So far, there is no evidence that he gave a reading on this visit, which clearly occurred in June 1927.

When her first collection, For My People, received the Yale University Younger Poets Award, Walker sent him an advance copy inscribed “To Langston–in gratitude for his encouragement even when the poems were not good.”

When her first collection, For My People, received the Yale University Younger Poets Award, Walker sent him an advance copy inscribed “To Langston–in gratitude for his encouragement even when the poems were not good.”

She said of Hughes, “I believe most of the Renaissance poets considered Langston their leader and their catalytic agent.”

• • •

1927

Hughes came to New Orleans in 1927 as part of his first trip into the South. Already with two collections of poetry published in two years during the height of the Harlem Renaissance, he had just completed his freshman year of college at Lincoln College, in Philadelphia, and scheduled June readings at Fisk University in Nashville and at a YWCA conference in Texas. But as a result of the devastating 1927 Mississippi River floods, he wound up visiting both Baton Rouge, which distressed him, and New Orleans, which delighted him.

He left by train for Fisk after final exams, but as he traveled south, word came of the floods and the cancellation of his Texas event. Instead of returning home after the Fisk engagement, he wrote, “I decided to see the South.”

Having never experienced Jim Crow, he was an easy foil for a prank played by Fisk students he’d befriended en route from Nashville to Memphis. Because their Jim Crow car was situated closest to the engine, Hughes wore dark glasses to protect his eyes from cinders. When the group got off the train at a small town stop to “stretch our limbs and buy some ice cream cones from a platform vendor,” Hughes recalls, one of them whispered in his ear, ‘Mr. Hughes, don’t you know the White folks down South don’t allow Negroes to wear smoked glasses.’ Quickly I snatched my glasses off and looked around to see if any White folks had noticed me wearing them! The students laughed loudly, then I new it was only a joke.”

From Memphis, Hughes went farther south, intrigued by the awful disparities in conditions for Black and White refugees from the floods: “The papers said a vast camp for flood refugees had been established in Baton Rouge, and that thousands of Negroes and Whites who had never been out of the plantation country before were being housed there. The Negro papers said the flood was a blessing in disguise, rescuing hundreds of Black field hands and their families from peonage. I felt like going to talk with these field hands, so I struck out for Baton Rouge. “

What he finds is appalling: Black refugees who’d been forced at gun point to work on levees even as they were giving way, their White bosses fleeing in all the available boats, leaving their Black workers to find the way to safety “as best they could” spending long nights on roofs or knolls or portions of intact-levee “fighting back snakes and little wild animals that sought refuge there, too.” Of the Blacks he talks to, their high level of illiteracy depresses him, as does their resignation that as soon as possible they’ll return to plantation labor at the guarded camp they called home: “they had no money; they knew nowhere to go.”

Hughes admits: “Baton Rouge depressed me terribly; so, having the money to go away, I went. I bought a ticket for New Orleans.”

Langston Hughes by Carl van Vechten 1939. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

He writes at length about his visit in The Big Sea: “In New Orleans, I wanted to live on Rampart Street, the leading Negro street.”

He first took a room near the L & N train station, at the foot of Canal Street near the river, where his landlady, he writes, “played marvelous blues records on an old victrola: Blind Lemon Jefferson, Lonnie Johnson and Ma Rainey, and sometimes a wild guitar player would come in off the street and plunk a while, providing somebody bought him a drink or two. In Baton Rouge and New Orleans I heard many of the blues verses I used later in my short stories and my novel.”

Wandering about, Hughes enjoyed the “amazing voodoo shops and drug stores.” He catalogs some of the contents of a window on Poydras Street that displayed “more than fifty conjure and voodoo preparations: High John the Conqueror Root, Go-and-Stay Powders, Love Lucky Load Stone, black cats’ bones, various kinds of incense, and tall, black luck candies. Signs announced: Good Business Water 25c; Follow Me Seeds, 10c; Genuine Calabar Spirit Beans Cheap.”

One of his purchases, Wishing Powder, brought him the unexpected good fortune of a quick side-trip to Cuba as a mess boy. After returning to New Orleans, he settled into the French Quarter for most of August “in the home of a colored woman married to a Mexican” a block away from the St. Louis Cathedral. It was a “picturesque house,” over a hundred years old, but “airless and the heat lay like a blanket and everybody left their doors wide open at night, and some of the roomers snored like frogs. Mosquitoes zoomed and hummed. And at dawn, the lady of the house got up and began to wash and clean and sing and cook in the patio, so there was no sleeping after the sun rose.”

He also observed “cockroaches as large as mice” that “came out of the cracks of the walls after dark and scraped their rasping feet over the stone floors.” His landlady, “a stout, dark woman,” made “very good coffee and a lot of it, for everybody in the house, so with the coffee and the sun and the singing and the bustle every morning, I found myself up early and out in the street rambling through the Vieux Caree.”

He describes an afternoon of wine-drinking with two caretakers in the St. Louis Cemetery, “with its tombs one on top of another above ground.” They were short “very black fellows, who spoke Creole to each other. They were the first real Creoles I had met”–and he attempts to define what makes one a Creole: “In Louisiana, it seems, a Creole is anyone, white, black, brown, or mulatto, who speaks the Creole patois or who comes from certain parishes where that patois is the local language.”

After visiting Marie Laveau’s grave, they have supper “in a nearby tavern for colored Creoles,” which he returned to often in his remaining days in New Orleans, as he “came to know several Creoles pretty well. Even once or twice I was invited to their homes, and on one occasion to a party.”

Another observation on the city’s class distinctions: “The non-Creoles said that the Creoles were a very dangerous people, given to the use of knives, and the Creoles said the same about the others. But I had a good time with all of them.”

Some accounts indicate that he met up with Zora Neale Hurston while in New Orleans and that, in her car, they traveled in the South collectiing material for their ill-fated play, but it seems more likely that this accidental meet-up occurred after Hughes had left New Orleans and was en route back to New York.

• • •

1944

Hughes’ biographers don’t mention a New Orleans visit in 1944. On the back of this photo, Xavier University archives identifies Hughes as “author and lecturer at Xavier University 1944-1945.”

Rampersad, by far the most detailed of Hughes’ biographers, writes that after stops on a book reading / signing tour during the week of February 14, with events in Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia, Hughes “continued on through Louisiana” but names no stops.

Langston Hughes with Fathers Murphy & Connay, 1944. Xavier U digital archives. New Orleans.

1951

Rampersad writes that in February while on a book tour, Hughes “loitered a while” in New Orleans. Throughout much of his life, Hughes enjoyed staying for a week or more at a time in cities with large Black populations and active night-lifes, away from academic and society types.

1953

On June 16, he stopped in New Orleans as part of a cross-country automobile trip to New York from Los Angeles, where he had testified at the HUAC hearings.

• • •

Sources

Alexander, Margaret Walker. “My Idol Was Langston Hughes: The Poet, the Renaissance, and their Enduring Influence.” Southern Cultures 16.2 (2010). southerncultures.org. 1 July 2023.

“Capacity Crowd Hears Langston Hughes at U.N.O.” Louisiana Weekly. 20 Feb. 1932: 4.

Graham, Mareymma. The House Where My Soul Lives: The Life of Margaret Walker. New York: Oxford UP, 2022. academic.oup.com. 2 July 2023.

Hughes, Langston. The Big Sea. 1940. New York: Thunder’s Mouth, 1986.

—.I Wonder as I Wander. 1956. New York: Hill and Wang, 1993.

Rampersad, Arnold. The Life of Langston Hughes. 2 vols. New York: Oxford UP: 1986, 1988.

The Tiger. New Orleans: University of New Orleans, 1928. archive.org. 2 July 2023.

Dillard University, Straight University, New Orleans University. lostcolleges.com. 2 July 2023.

“Walker, Marion Dozier (Mrs. Sigismund C.)” Obituary.3 Apr. 1983. Louisiana Conference: United Methodist Church. la-umc.org. 2 July 2023.

Marion Walker, director, is at lower right. The Tiger, New Orleans University annual, 1928.

—Alex Albright

October 15, 2023