Evelyn Whorton, m.c. with Dorothy Lee, Gracie Mae Shavers, and Willie Jones. Pitch a Boogie Woogie, 1948.

Willie “Ash Can” Jones uncredited extra

Willie Jones may have had a dancing role in “Pitch” had not his partner, Pearl Edwards, gone back to New York along with two other dancers, leaving Jones and the Count & Harriet behind. They had been traveling with Irvin C. Miller’s Brownskin Models as the Six Swingsters.

They were all talented dancers and veterans of the famed Harvest Moon Ball swing dance competitions that were held annually at Madison Square Garden–all six were finalists in 1945. But, Jones said, they were not used to the conditions they had encountered on their Southern tour: a sleeper bus with a 500-gallon tank of water for use with a bucket to wash up with. “They were used to rooms and bathrooms,” he said.

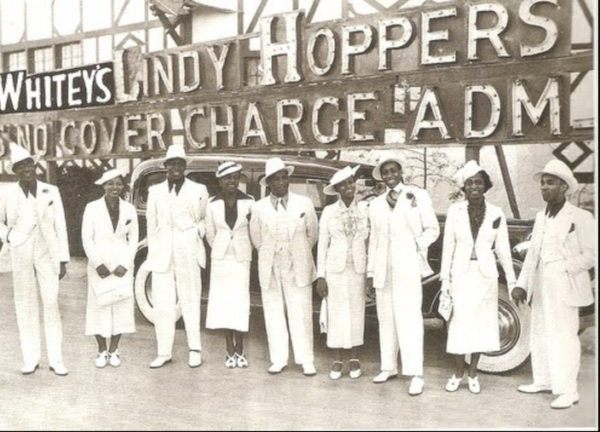

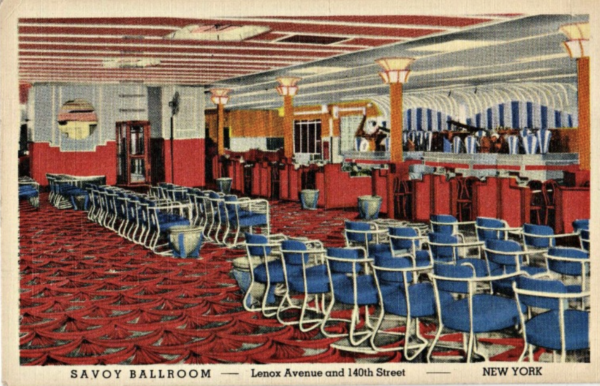

Jones was born in 1910 in St. Kitts, Virgin Islands. He came to the U.S. first in Florida, after his father jumped ship there (he’d been working on a banana boat) and then brought his family along. They moved to Georgia, then Atlantic City, where Jones began dancing. In 1929, Jones moved to New York City, where he stayed with family, which included Bubba Gaines, a dancer with the Three Dukes. Determined to dance, Jones shined shoes and pushed hand carts about the garment district by day; at night, he went to the Savoy to dance, where he met some of the best of the first generation of swing dancers, including Shorty Snowden (1904-1982), said to have been the first to call the jitterbug “the Lindy Hop”; Leon James; Ralph Henry; Leroy Jones; Sugar Cook, Little Jerome, the Sheik; and Shoebrush Austin. They taught him dance moves that he showed off in the legendary Cats’ Corner, and his most important contact at the Savoy was a bouncer, Herbert White, who controlled that corner. White was, among other things, an ex-prize fighter, Army sergeant, and founder and leader of the Jolly Fellows, which Jones joined. Marshall and Jean Stearns report that White demanded “unquestioning obedience” from his Fellows, who in return were “given protection and a place in the sun”–a safe place to roam in the blocks around 133rd – 135th street between 7th and 8th avenues.

The Jolly Fellows was one of a dozen or so “secret” gangs operating in Harlem; that is, they didn’t wear jackets with their names and shields emblazoned on them. Others included the Meteors, “a friendly group,” the Stearns write; the True Pals; the Buffaloes; the Harlem Habits, and the Forty Thieves. Because of its founder’s interest in dance, and also the successes his dancers enjoyed, the Jolly Fellows became the club for dancers, and the Savoy its showroom. The Fellows were formed in 1923 out of necessity, its early members said. “The kids were beating me up every day,” one recalled, “and it was the only way to survive.” Another said, “We could see that things were falling apart–buildings, streets, people, everything. It really meant something to belong to the Jolly Fellows.” Membership eventually grew to over 600 in the mid-1930s; the Jolly Fellows protected their territory and members with a power greater than the NYPD’s in Harlem. They operated “outside the law,” the Stearns write, “a precursor of the street gangs to come. There was plenty of violence in those days, but the papers never gave it much space–it was expected of Harlem.” The Stearns recount one brazen and gruesome execution carried out without consequence by the Jolly Fellows of a Buffalo in the Renaissance Ballroom, which occupied an entire block on Adam Clayton Powell Blvd. between 137-138th streets but was outside the Jolly Fellows’ territory. The pianist Claude Hopkins described his work at Fulton Gardens in 1928-29 as a battleground for the gangs. He said, “At least [the manager] always took the trouble to tip us off before a battle was supposed to start–You have to remember, though, that this was all during the Prohibition era, and a lot of clubs were like that.”

The Renaissance Ballroom, before its demolishing. abandonednyc.com

Despite its violent aspects–if a Jolly Fellow were beaten by members of a rival gang, retribution included “death for the leader of the gang that beat him up”–the gang had certain rules that were chivalric. All women were to be treated “with unfailing courtesy.” Fights must be “fair”–that is, adversaries should be equal in number and if one side is unarmed, so too must the other side be. The had two rules, the Stearns writes: “Never fall down in a fight, and don’t run unless you have a good exit all picked up.”

Post card mailed 1941. newyorkcityinthewitofaneye.com

Jones recalled that he and his partner and Snowden and his partner were such good dancers that they were admitted free to the Savoy, because they were so entertaining and were also teaching the hostesses how to dance. And in addition to giving them a safe place to dance, White also “insisted on personal cleanliness,” keeping a comb, rubbing alcohol, “and Fels-Naptha soap handy, which he personally applied to any boy, dancer or not, who had the slightest trace of body odor.”

During the early 1930s, Jones also earned money dancing in competitions at the Lafayette Theater and the Cotton Club, where he worked with bandleader Claude Hopkins (1903-1984) in 1934, not long before Herbert White began formally organizing Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers. Hopkins also held a residency at the Savoy from 1929-1931, so it’s likely Jones was familiar with dancing to his band’s music. But by the mid-1930s, Jones was no longer among the youngest dancers, so a new generation, led by the more famous Norma Miller, began getting Whitey’s best gigs.

Norma Miller (1919-2019) burst on to the Harlem dance scene as a high school student in 1935, when she and a partner defeated four teams of Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers at the first major Lindy competition, held at the Apollo Theater. Then, as part of Whitey’s troupe, she and Frankie Manning (1914-2019) were finalists in the first Harvest Moon Ball. As part of the second generation of Lindy Hoppers, they elevated swing dancing from a couples’ entertainment and competition into big cast stage routines. In 1936, they anchored Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers European tour and back home they remained dominant dance forces for years–they’re featured in Hellzapoppin (1941). Miller wrote in her memoir: “Whitey wanted new dancers who would start where the old ones left off.”

Willie Jones said:

I was with Whitey before Norma and Frankie [Manning] and everyone. I could dance just as fast as they could. But when they came in, they were younger and had new idea for moves and routines. So Whitey put me in the smaller shows, though I sometimes substituted in the big shows when someone got sick because I knew all the routines.

But Whitey used lots of dancers for the work that came his way after the great successes at the Harvest Moon Ball, which drew 20,000 spectators to its Madison Square Garden shows from 1935 into the 1950s. Movie, theater, and traveling show producers came to him, and he in turn worked as many as 70 dancers and a dozen dance troupes.

Courtesy of Willie Jones.

Although Willie Jones was one of the old ones, he continued to dance professionally with jobs provided through his association with Whitey’s, and to work as a comedian, Ash Can Jones.

He played Broadway at the Barrymore in 1938 in the cast of Knickerbocker Holiday. His scene, with seven male dancers from Whitey’s performing as a band of Algonquin Indians, started out at about 5 minutes but had been reduced to 90 seconds by the time it opened on Broadway, “because we were too good,” Jones said. The dancers exhibit their ferocity in a “frenzied Lindy routine” attack on Rip van Winkle (Walter Huston). Jones also dances, uncredited, in the famous jitterbug scene in the Marx Brothers 1937 movie A Day at the Races.

Whitey continued to find work for Jones and his dancers, including jobs for the Six Swingsters, and Jones remained grateful:

Whitey did something for us that nobody else would have done. We were poor and he helped us get money. We didn’t know nothing, and Whitey turned us into ladies and gentlemen. But most of all, he made people respect us, and made us respect ourselves.

He and the Six Swingsters were working as a team after World War II, when they joined Irvin C. Miller’s Brown Skin Models.

Willie Jones at home in Philadelphia. UNC-TV, 1988.

Jones vividly recalled meeting up with Irvin C. Miller in 1946 to arrange work for the Six Swingsters:

I was coming down 125 Street and I met Mr. Miller. He says, “Willie, I’m getting ready to take a show down South, I’m getting the Florida Blossoms and the Brown Skin Models combined, we going to be combined under tent. We got two sleepers. So he asked me, he wanted my dancers. The Harvest Moon Ball was over–we done made what we going to make out of that, for our names. So I brought ’em to rehearsal. He wanted me to sign a contract. He asked what I would take for them. I said, “I’ll take $360–that’s six people now. That’s what I’ll take for six people.” He told me Yeah, he’d sign the contract. We jumped out of here and jumped into, well, some rehearsal, and went from here to Norfolk, Virginia, and me and the people with all the tents and everything, and we started rehearsing and got the whole show together and we played there a week.

Greenville Daily Reflector, 22 July 1947: 7.

If Jones’ chronology is correct, this would have been after the 1946 Harvest Moon Ball, at the start of what would be the Models’ 1946-47 season, which would take them at least through July 1947 when they played Greenville and John Warner’s Plaza Theater.

With the Models, Jones worked as stage manager, talent scout, and dancer. He had worked with Miller off and on since the early 1930s, first on a touring revival of Shuffle Along and then, after World War II, more regularly as Miller tried his hand at managing a Southern tent show, the Florida Blossom Minstrels, which for part of the 1946-47 season worked in tandem with the Brown Skin Models on a tour that did not go well.

Audiences after the war became increasingly difficult to find in DC and the north, and for many entertainers, the Southern routes were their only options to make a living as a performer, and Miller saw the territory as wide open. His plan was to rule both the theater and tented vaudeville. But he had difficulty keeping performers on the Southern routes–everyone, it seemed to Jones, was quitting and going back to New York, citing the usual: travel, working conditions and pay. So Miller abandoned the tented portion of the tour and reverted back to theaters and in-door vaudeville, in the process losing most of his tent show equipment in a scam perpetrated by someone he thought had been a partner.

Of the Six Swingsters, Jones called only their first names in our interview–Pearl, his partner; Jessie & Blue; and the Count & Harriet. Jones said they all danced with Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers and as couples competing in the Harvest Moon Ball, and it’s easy to see that roster in the finalists at the 1945 HMB at Madison Square Garden, and to fill in their names: Willie Jones & Pearl Edwards; Jessica Cookley & James “Blue” Outlaw , “one of the top Lindy Hoppers still around,” and Harriet Drayton & Count duBarry, or the Count & Harriet. Bobby White, whose Swungover webpage offers the most comprehensive Harvest Moon Ball history I’ve found–lots of great videos included–suggests that “duBarry” wasn’t his real name.

The Susan Massengale Papers at UNC-Chapel Hill include six tapes of Willie Jones interviews made in the production of Boogie in Black and White.

Willie Jones & Alexander Shavers, courtesy of Willie Jones.

• • •

–August 31, 2024

Sources

“Claude Hopkins: Life of a Jazz Pianist.” John D. O’Bryant African-American Institute. www.northeastern.edu.

Crease, Robert P. “Profiles of Original Lindy Hoppers: Willie Jones.” The New York Swing Dance Society: Footnotes. 5,1, 1990. www.frankiemanningfoundation.org/. 30 Aug. 2024.

“The Jolly Fellows, Herbert White, The Hoofers’ Club & the Jitterbug.” Harlem Dramaturgy Project, Part 5: Once Upon A Time In Harlem: A Jitterbug Romance. 13 June 2012. africanamericanplaywrightsexchange.blogspot.com.

Jones, Willie. Personal interview. Philadelphia, PA. May 1988.

Miller, Norma, and Evette Jensen. Swingin’ at the Savoy: The Memoir of a Jazz Dancer. Philadelphia, Temple UP, 1996.

Stearns, Marshall and Jean. Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance. New York, Da Capo, 1968.

White, Bobby. Swungover. Swungover.wordpress.com.

This is an incredibly detailed webpage that includes lots of vintage video footage and a year-by-year accounting of the Harvest Moon Ball competitions.