Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels chorus line, from “Pitch a Boogie Woogie”

Billy Cornell Girls, chorus dancers

Billy Cornell was in charge of Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels’ dancers, who perform during two songs and again in the Grand “Finale of Pitch a Boogie Woogie.” Their routines are performed to music played by Don Dunning’s orchestra and, at least in the film’s finale, by the Rhythm Vets.

How the two dance troupes credited in the film, identified as “the Irvin C. Miller girls” and “the Billy Cornell girls,” came to share credits is not entirely clear, but it appears that Cornell was stage manager for Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels. Both Cornell and Miller were well known producers with national name recognition to Black audiences, whereas Winstead was not. Winstead’s show and Irvin C. Miller’s Brown Skin Models were both playing Greenville, NC during the summer of 1947, Miller’s troupe at the local Black audience theater run by “Pitch”‘s producer, John Warner, and Winstead’s under tent for an extended stay. Both shows were already popular with Greenville’s Black audiences and familiar to Warner.

Miller, a much under-appreciated force in Black entertainment during the first half of the 20th century, is nonetheless heavily documented in the Black press during those years. Like Miller, Cornell was versatile, cleveer and creative.His own impressive career as a comedian, dancer, actor, promoter, producer, and show owner spanned over 30 years; he worked throughout the United States, Canada, and in Cuba, with many of the best known entertainers of Harlem, Chicago, Baltimore, Washington, DC, and Los Angeles. But so far, I’ve found no documentation of his career or life prior to 1920.

In February 1920, headlining as the Candy Kid, he played a return engagement at the Washington Theatre in Indianapolis, in a vaudeville bill that included Charles Arrant, Dude & Georgia Kelly, and Baby Mack. A reviewer wrote that Cornell played “with much success” with his “comedy singing and dancing act.” The “large audiences every night” responded with “heavy applause and many encores with which his blackfaced features are are being received.” His show especially appealed to those who favored “good healthy and absolutely non-suggestive jokes.” His musical numbers: “The White Folks Caused the War to Start, Black Boys Caused it to End”; “It Can’t Be Done”‘ and “Breeze.” Overall, “Billy’s Candy Kid is very good and clever. It’s going bigger and bigger.”

So many dates over the next three decades find him in Ohio that it seems possible he was from there, but most of what’s reported on him in the Black press is publicity related; only once have I found an official record of sorts, a marriage announcement in 1926, when he seems to have made Baltimore a locus of his performance adventures, perhaps because his bride and fellow comedian Hazel Wallace was from there, or had been living there.

Throughout the 1920s, Cornell worked primarily in vaudeville in theaters as a solo or with a partner, and often on a bill with others. By 1923 he had the Billy Cornell Company, which morphed quickly into Mme. Bruce’s “In Bad” Company, headlined by Billy Cornell and featuring a chorus of “ten Creole beauties.”

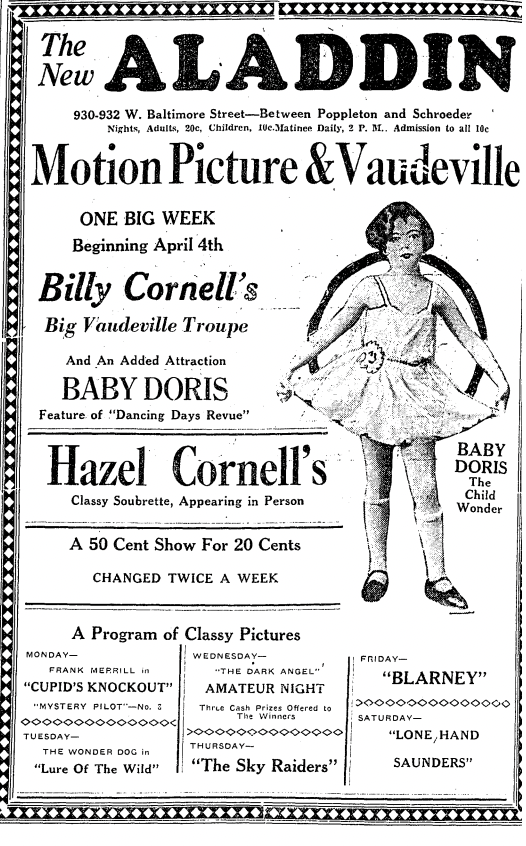

Baltimore Afro-American, April 2, 1927

Baltimore Street, 900 block west, looking east, 1920, A sign for the New Aladdin Theater is visible in the center of the photograph. Hughes Photograph Collection, Baltimore City Life Museum Collection, Maryland Center for History and Culture

His own company, Billy Cornell’s Dancing Dandies, got closed down at the Palace Theater in Lake Charles, Louisiana, in 1925, canceled after its opening performance of a week’s stand. The “large audience” was “very loud in denouncing the offering. Much of the material was suggestive,” the closing bit “offensive in its entirety.” Cornell and cast left town the next morning.

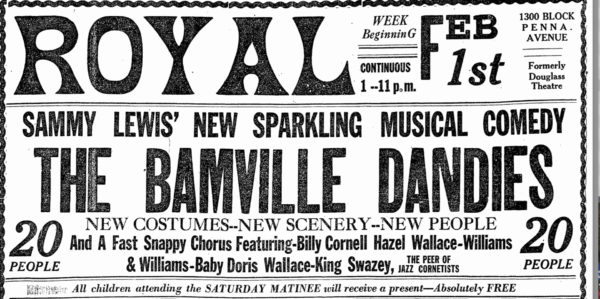

In 1926, he was working with Sammy Lewis’ “Bamville Dandies,” which was a big hit at the Royal Theater in Baltimore for a week’s run in February. Edwin “King” Swazey led a 9-piece jazz band, Kid Lips [Hackett] “brought em a Charleston on his hands, and the house ‘came down.’ Cornell and John Williams were “two comics who mix intelligence with their art.” They were “as popular as the paymaster on Saturday throughout the evening. Comics who don’t overplay are so rare these days that the work of these fellows is remarkable.” The show moved on to the Lafayette Theatre in New York where a reviewer called Billy Cornell’s comedy “a riot.” Hazel Wallace was one of the show’s chorus dancers. They married on April 14, 1926, after the midnight show, with her daughter, Little Baby Doris Wallace, who had been starring in the show, as the flower girl. They subsequently became the Dixie Three and led and managed and then owned the minstrel show on Harry Coppin’s show.

Baltimore Afro-American 30 Jan. 1926: 4

By about 1927, Billy and Hazel Cornell appear to have split up: He began billing himself as “A Dark Cloud with a Silver Lining” and for a while had his own “big vaudeville group” before joining the Dixiana Company. Meanwhile, “Hazel Cornell’s Dancing Days of 1927” carried 15 performers and was held over for a second week at the Aladdin Theater in Baltimore before moving to the Savoy in Atlantic City. For a while, Cornell worked as part of “Hazel Cornell’s Revue” performing for White theaters but soon he was working on his own and then with others again on the Black circuits.

As a solo with the Dixiana show in 1927, his 5-piece band and their comedians were arrested at McKeesport, Pennsylvania in a 10 a.m. raid. But by the time Cornell could get back to the station with bail money, the group had put on an impromptu show of their own, performing “Jail House Blues” and “I’m in the Jailhouse Now,” earning their freedom at no cost.

Billy Cornell’s “Broadway Follies” of 1928 was his biggest success. “The last word in high-class entertainment,” it combined the “cream of the best delineators of Ethiopian comedy the stage ever harbored.” The cast of 25 artists included a “whirling dashing dainty chorus of youth and beauty, a garden of brown-skin beauties.” Their array of costumes was “the smartest ever seen with a show of this style and order.”

By 1929, Cornell was back with Sammy Lewis (“the record & radio star”), on his “Plantation Days” show. Cornell denied a report that the show had been stranded. Someone reported to Chicago Defender columnist Bob Hayes that Cornell had been stranded with the Sammie Lewis Company in Texas, where they had been “saved” by the entertainer Chintz Moore. Cornell then wrote to Hayes, on Plantation Days letterhead, that he remained the star of the Sammie Lewis Plantation Days Company and “they are all okay.” Hayes warns, “Now lay off that rough stuff.”

In 1930, Cornell was back with Hazel Wallace and her daughter, Doris, touring a revived “Broadway Follies” company, with Sam Thread, “the record artist known as Loving Sam from Alabam”; Hazel and Doris, “a miniature wonder”; “little William Walker”; and a chorus of 8 dancing girls. By mid-year, he had joined the Greater Sheesley Shows as stage manager, working in Canada, and then, teaming with Myrtle Strand, the Sam Roberts RKO show as “the Two Dixie Steppers.”

He opened the 1931 season with Silas Green from New Orleans, in Brunswick, Georgia, and was still with them in September, in Nashville, Tennessee.

In 1932 he was leading a show working in Ohio when he “signed a contract with Paramount,” intending to leave for the West coast in May; in June and July he worked dates in Ohio and Michigan.

In August 1933, with Coleman Titus’ High Brown Flashes, he crossed paths with Irvin C. Miller’s Brown Skin Models in Cleveland, when they were booked at competing theaters for the same evening. Cornell was teamed with Leo Boatman as “Two Dark Clouds of Joy.” In October, as “the crooning comedian,” he was with the Crazy Quilt Company #2 in Baltimore.

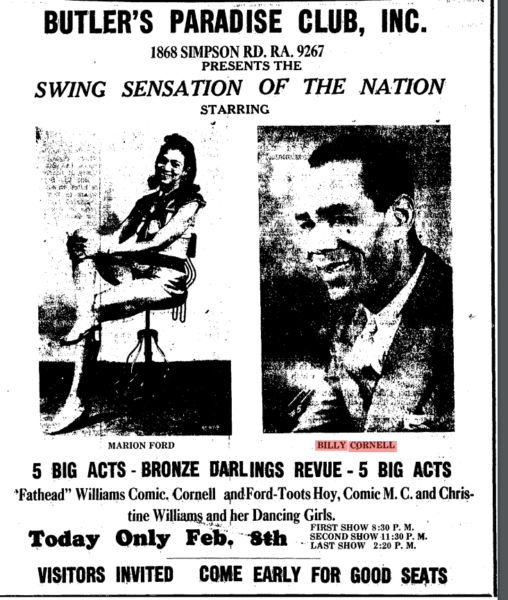

By early 1934, he and Marion [often spelled ‘Marian’] Ford were working vaudeville as “the Two Dixie Brownies,” Lindy hopping comedians, and they would remain an act into 1950.

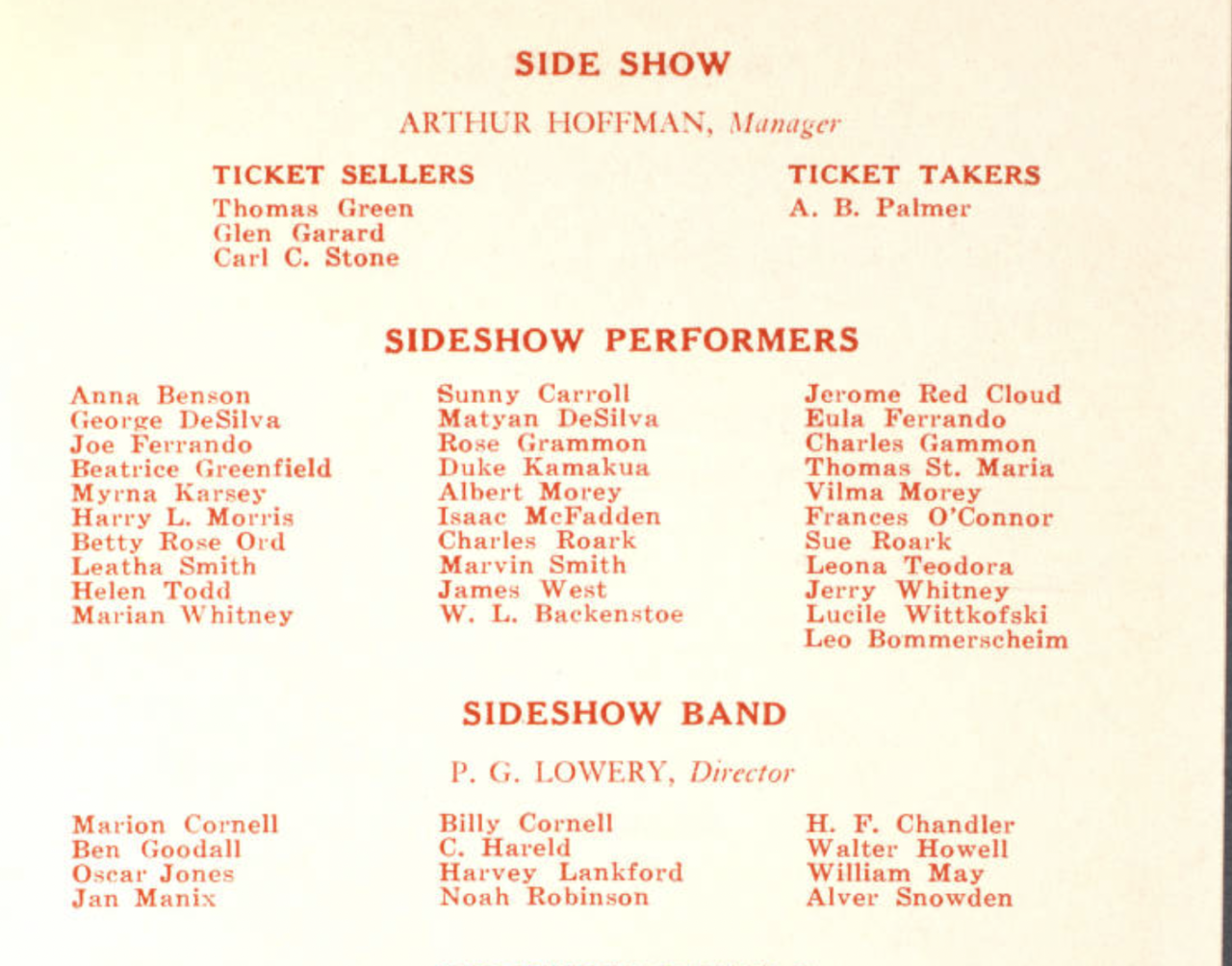

Cole Bros. Circus Routebook 1942. Circus Historical Society, Baraboo, Wisconsin.

During his many years with Ford, he also worked as stage manager for Harry Hunt’s Sugar Foot Green Show and then F.S. Wolcott’s High Brown Follies; with Silas Green from New Orleans and then the Miss Dinah Lee Company; with P.G. Lowery’s side show on the Robbins Bros. Circus; and as sideshow manager with Cole Bros. Circus with Lowery, and with whom Cornell also worked Ohio theaters during off-season. For at least part of the 1939 season, they had their show, “The Harlem Strutters”; in 1943, their “all-girl revue” ran for a month at Pope’s Hotel in Erie, Pennsylvania, after which it played Buffalo and Cleveland. In 1944, as a duo back in Baltimore, they were part of a USO show that entertained over 1,000 troops at Holabird Depot.

Atlanta Daily World, Feb. 8, 1948Ford & Cornell worked together on Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels in 1939, when he was stage manager, and then on their own shows called variously the “Harlem Strutters,” “Billy Cornell’s Revue,” and “Down Georgia Way.” In May 1942, they were with P.G. Lowery’s band and sideshow working the Midwest with Cole Brothers’ Circus.

But Black vaudeville is not well documented during World War II and the post-war period. Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels stayed on the road during most of that time, and as one of the last of the successfully traveling Black cast road shows, it’s quite possible that Cornell worked with them again prior to their 1947 appearance that was filmed in Greenville, NC for “Pitch a Boogie Woogie,” and that he and / or Marion Ford are among the uncredited performers.

Cornell and Ford were with P.G. Lowery’s band and sideshow attached to the Cole Brothers circus in 1942, and with Alberta Snowden in early 1950 when they survived a “near fatal” automobile accident, and so far that’s the last notice of him I’ve found.

-June 22, 2025

Sources

Arnold, W.R. “Broadway Follies Scores Triumph. Pittsburgh Courier 14 July 1928: 7.

Billy Cornell’s Revue at Pope’s Hotel in Erie, Pa.” Baltimore Afro-American 20 Feb. 1941: 8.

“Broadway Follies.” Chicago Defender 14 July 1928: 7.

“Doings of the Profession. Chicago Defender 27 Dec. 1930: 5.

Hayes, Bob. “Here and There with Bob Hayes.” Chicago Defender 23 March 1929: 7.

“Lowery Band Heads a Fast Circus Show.” Chicago Defender 9 May 1942: 23.

“Silas Green Ready for Spring Tour.” Chicago Defender 28 March 1931.

Stanley, G. “The Washington Theatre, Indianapolis, Billy Cornell (Candy Kid).” Indianapolis Freeman 7 Feb. 1920: 3.

Taylor, J.A. B. “Canceled for Smut.” Chicago Defender 21 Feb. 1925: 6.

Tyler, George D. “Cleveland Theaters.” Baltimore Afro-American 10 May 1930: 9.

—. “Tyler Visits Two Harlem Theaters.” Baltimore Afro-American 20 Feb. 1926: 5.

Varnell, Wesley. “Varnell’s Review.” Billboard. 19 May 1923: 53.

Also entertainment notes and routes from the Chicago Defender and Baltimore Afro-American.

Billy Cornell, 3rd from right; Marion Ford, 5th from right. Baltimore Afro-American. 16 Dec. 1944: 6.