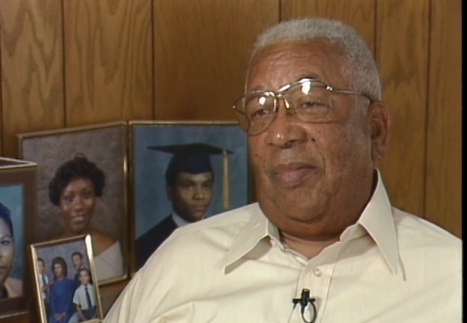

Thomas Gavin, UNC-TV, 1988.

Thomas Gavin, alto saxophone

Thomas Gavin grew up in a musical family in Lumberton. “My mother was a music teacher, a piano teacher,” he said, “and she had taught in public schools.” But after he and a brother were born, “She did most of her teaching in the home, private lessons, and she started both of us on a piano, but it wasn’t popular for boys to play piano, and we got quite a bit of ribbing about it and unfortunately we listened to our peers and we quit piano lessons. I came home one day and my mother and my uncle, who was a saxophone player, had gotten together and purchased a little soprano sax for me, which I still have, and I took lessons from my uncle and he taught me quite a bit of music theory and fundamentals. he only went for about a couple of years with me because I thought that after I had learned to play the horn, I sat down by the radio and started playing and I thought I was above learning any more theory.”

Although his high school didn’t have a band, he passed the band audition at A&T–administered by future fellow B-1 bandmate Willie Currie, 2 years his senior and who also wound up, like Gavin, teaching in Fayetteville for most of his career. Gavin was completing his freshman year at A&T when they enlisted with most of their fellow Aggie bandmates.

At their induction, he was behind Charles Woods; both were born September 23, 1923, he said, and laughed before continuing: “The Navy guy says ‘You trying to be funny? Everybody can’t have the same birthday.’ But we did.”

L to R: Charles Woods, Thomas Gavin, Walter Carlson–all Rhythm Vets, and Melvin Thomas, in Hawai’i

“I guess some of us thought the Navy was going to be different, he said, “but we’d become used to that stuff. All the facilities were segregated. The Navy was nothing that different. I had just left a segregated school. We rode up on a segregated train; the hotel in Raleigh [where they were inducted, May 27, 1942] was on a back street in a blighted part of the city, segregated. It was the same.” In the Navy, he played with the number one dance orchestras in Chapel Hill and Hawai’i, and in smaller combos: “We were ordered to play at officers clubs almost at will–theirs, not ours.”

Once back in Greensboro after the war, he resumed school and was one of the original Rhythm Vets. “We were having difficulty in paying our bills, and that sort of thing,” he said. “We were all in school on the GI bill. So one night, I think it was at my house, the guys were discussing how we could supplement our military income and the idea came up. We’re musicians, why don’t we form a little band? We might make some money. So we did. I think one of the wives furnished that suggestion, I don’t remember which one. To our surprise, we were in demand in just a short while, and we played for high school proms, dances at the college–most of the jobs were school jobs. Then we started traveling more, and we got around very well, we were in demand, that was before disc jockeys and disco and that sort of thing, so everybody that had an affair, they wanted live bands. It was hardly thought of to have records for a dance at that time, so we got along pretty good and we were really able to supplement our income.”

Because the Vets had gone through so much together, in school and the Navy, he said there was “a closeness to them, where you could almost feel what the other was going to do.” Most of them also played with the Max Westerband orchestras, where their performances were “a lot stricter” in what they could individually play. “But we [the Rhythm Vets] had a group name, so you were free to do much of what you wanted. We played all kinds of music. We’d play anything. We were very commercial. We’d do country and western if we had a job.”

Buck Gavin in center, cradling his horn, with the Rhythm Vets, 1949, from the Ayantee, A&T’s annual.

The Vets, he said, had as many as 300 arrangements, many by Dan Alexander, sheets “you could get in good music stores.” They also had several special arrangements and played “some head arrangements, where we just blew, but mostly stock stuff.” ‘Flying Home’ was a good one for fast dancing. ‘Old Lamplighter’ was popular. We’d playing anything from Lombardo to Basie–they’d be Lindy hopping, jitterbugging.”

His recollection of the sometimes exciting rides to and from gigs began seriously but soon turned to laughter: “I had a car that I had sort of assembled, I was studying auto-mechanics at A&T, and I had a car that I had assembled from several other cars. I started driving my car, since we needed two cars to travel in, and the other car that we used was a car that belonged to Charles Woods. And often, we would try to take each, either of us would try to take the lead, and we felt that the one that got there first was really the more efficient in the transportation department, so we would either try to leave early or either try to catch up to the other and get to the job first. And often we would do some pretty silly thigs, passing each other in places where we shouldn’t, that sort of thing. We went through things that we wouldn’t do again. But we used those two car, mine being an old ’35 model and his car was a couple of years younger. And we would actually compete in our transportation.”

Personally, he said: “I was 40% influenced by Charlie Parker, if you could figure it like that.”

I asked, Where’s the other 40%? and he laughed. “Everybody else,” he said, and paused before naming Willie Smith, Johnny Hodges, and Benny Carter.

He recalled having been to Greenville prior to the recording of “Pitch a Boogie Woogie” with the A&T Marching band, when they went to a theatre and made a recording–no doubt John Warner’s Plaza Theater–with the A&T marching band. That one was “a disk type recording,” he said. “They moved the piccolo player [Abe Thurman] five times–they had to arrange instruments according to the equipment they had.”

Warner had also heard the Vets play in Greenville at a dance at Eppes High School. He remembered making the “Pitch” soundtrack because Warner used “the first tape recorder I’d ever seen–a cabinet type thing.” The recording “was quite grueling,” he added. “We worked all night and the next day until the afternoon.” He said Warner was a businessperson on the job: “He was quite stern. He and his brother [William Lord] were there the whole time. His brother seemed to take more of an interest in the music. He was quite interesting. Warner seemed more the businessman.”

Gavin also recalled the difficulty the Vets had in trying to synch their music with the film: “We were playing after the fact, after something that had already taken place, and we were trying to fill in. It was really like work without a lot of results of pleasure being seen immediately.”

The soundtrack they made “could’ve been better, could’ve been more rehearsed. They didn’t have that kind of time. But I’m certainly not ashamed to be identified with it.”

He was especially pleased with the Grand Finale: “On the last number, the style has changed. It was modernized quite a bit. Foster was playing chords from progressive jazz, and the solos came up to more of a ’47 style. We got out [of college] at the height of the bebop era. We referred to it as progressive jazz. Lou Donaldson was really into it.”

When first reminded of his role in making “Pitch,” some of his memories were uneasy and his feelings remained mixed: “I had a certain feeling about “Pitch a Boogie Woogie” after I found out that it had been restored. The immediate thing that came to my mind was the old minstrel shows that you used to see a long time ago, and to be perfectly frank, I had some apprehension about that movie and this time. My mind kinda went back to the times of the old minstrel shows, and I remembered some things in there that I’d seen that I wouldn’t care to see again. But after seeing the movie, I had a better idea, some new idea of acceptance of it.”

“But I found it to be a very clean type of film,” he explained. “The language was very good, there isn’t any vulgar language in it, the dancing is good, there’s no vulgar dancing, and it’s a far cry from the actual thing that we see today on television, It’s rather quaint. I wouldn’t mind my children looking at it and I don’t feel as badly about it as I thought I would feel.”

Like most of the other Vets, he enjoyed the chance to perform together again, after “Pitch” re-premiered in Greenville in 1987. “That reunion is about the best thig to come out of all this,” he said. “I hadn’t seen Foster more than once or twice since then, I hadn’t seen Donaldson. He was as good as I’d thought he’d be.”

Gavin graduated from A&T in 1949, majoring in industrial education. “I couldn’t get a job in industrial ed,” he said, “but everybody it seemed wanted to start a band after the war, you didn’t have to have a music degree to start one, and I had enjoyed band.” On his first application, “They said, “You can start tomorrow if you will start a band.’ So he taught industrial ed while beginning the band at Upchurch High School, in Raeford.

He modestly explained how Fayetteville State University’s band began. Someone at Fayetteville State noticed his work at Upchurch, he said, “And they decided to start a vocational program and also wanted to get a band started, so for a year, “The president looked to me to fill two positions then, teaching auto mechanics and directing the band–and that’s how the band at Fayetteville State started.”

He subsequently taught in Asheboro and Lumberton before E.E. Smith High School, from where he retired in 1991.

Since 1950 he lived in Fayetteville, where he and his wife, Martha Trice Gavin, also a school teacher, raised their children, Tommie, III; Jimmie; and Martha Briddell.

He also played music with several groups–“There never was a time I’ve not played since the Navy,” he said. In addition to playing with Max Westerband and the Rhythm Vets, while living in Greensboro he had his own small combo that played local gigs and at the Artists Guild–“all head work”–and played with Frankie Carol’s band. In Fayetteville, he was the only civilian member of the 82nd Division Band. He also played with the Harry Vincent Band band, and for 22 years he played with the Paul Reichle Trio.

Gavin explained why, though, music was always second to his family: “I have always been a home person, and I’ve always known that in order to make it big in music you’d have to leave home and go on the road. I did get a small taste of what the road was like in college, and since that time I did not choose it. In addition to that, I once had a band of my own for a while, and I discovered a lot of difficulties in running a band, many problems that you wouldn’t imagine, like looking for guys just before a job, and finally coming on the job with a headache and having to play the job, and the same thing to look forward to for the next job, and I decided that wasn’t for me. I’d just play with some other band and not worry about the problem of operating the band and managing the band and traveling.”

• • •

Sources

Gavin, Thomas. Telephone interview. 18 Feb. 1985.

—. Telephone interview. 23 Apr. 1986.

—. Personal Interview. Fayetteville, NC. 12 June 1986.

—. Personal interview. Fayetteville, NC. July 7, 1987.

–March 3, 2024