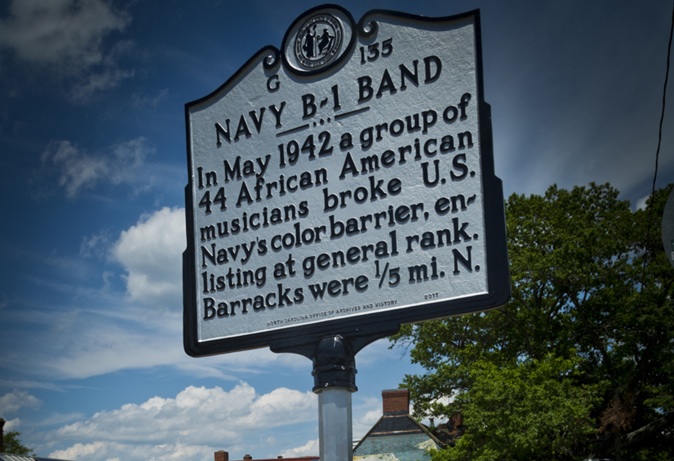

On several occasions, I’ve addressed this question: What’s an old White man like you doing in a place like this? Most of the time, my answer is related to the many doors that opened as I researched “Pitch a Boogie Woogie” and then, especially, the U.S. Navy B-1 Band.

Rarely have I had the time or the appropriate audience for this more personal background.

I was grown before I realized that I had, in fact, grown up during Jim Crow, that it wasn’t some historical era that pre-dated my life, like World War II. How that’s possible, I think, is part of the privilege some White people enjoy, like having a local members-only swimming pool that excludes your Black neighbors first by selling out of memberships before its plan is publicly known and then with a policy that prohibits in-county guests. Interviewing those B-1 fellows, I thought often of that special summer place, three blocks from my home, an easy bike ride away, as they talked of being taught to swim in creeks and ponds, sometimes of not having learned until they were in the Navy, training at Norfolk. At Chapel Hill, their first duty station, they’d not be given privileges except on Sundays, the day Kessing Pool was drained and cleaned– and fouled by white sailors urinating in it on Saturday.

I’d learned with a class of family friends daily car-pooled to Chapel Hill while we were in elementary school; knowing how to swim was part of our privilege, and it didn’t matter that we didn’t know this lesson had been part of a preparation to survive future disasters, that parents of our neighbors might be stressed to find appropriate ways to teach their children this survival skill. Our lessons were in Kessing Pool.

Growing up in Graham, I knew no one who had ever had a cloth placed on her head so she could try on a hat, put there by the sales clerk so a Black woman’s hands wouldn’t touch it, nor the hat her head. “Then they’d take that cloth by the corner,” Katie Abraham told me, as she demonstrated how the clerk would pinch the cloth’s edge, “and they’d drop it in the trash like it stunk.” Then she’d laugh. Katie was featured dancer with Silas Green from New Orleans during the late 1920s. She was one of over 30 African-American performers who traveled with tented vaudeville shows during the decades surrounding World War II and whom I met in homes and rest homes in the Carolinas, Georgia, Virginia, Mississippi, Louisiana, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Nevada, all as a result of leads I’d encountered while asking questions about Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels and Irvin C. Miller’s Brown Skin Models, who were featured acts in “Pitch a Boogie Woogie.” They, like the men of B-1 and their wives, were always gracious instructors, patient and even sometimes amused at my questions. Mattie Sloan, Winstead’s bookkeeper, cook, seamstress, and assistant for many years, her husband his band leader, seemed to have been waiting for a long time for someone to knock on her door and ask her to talk about Fat Winstead and his show. And as I was preparing to leave after our first afternoon’s visit, she presented me with Mose McQuitty’s routebook. I would return to visit with her dozens of times before she passed; we tried a couple of times to find the grave yard where she was certain McQuitty had been buried, in Fayetteville, but its space seemed obliterated by development. She was always a gracious host, a terrific cook, and a charming and dramatic story-teller.

I was also grown before I realized what Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come” was about, an embarrassing ignorance clearly based on not having heard the lyrics. For how many years did it play on the radio, an oldie transporting me back not to frustration and rage at an oppressive society but to slow dancing with R at a party in someone’s basement? How could anyone have been as oblivious as I to have glossed over the part about getting denied admission to a movie theater, followed by, “I go to my brother and I say, brother, help me please, but he winds up knockin’ me back down on my knees”?

[A cultural timeline update: Only recently did I learn that these lines were omitted on the 45 RPM of “A Change,”– the version we had danced to after it was released posthumously in late 1964; the original lyrics remained on the LP version of the song, and that’s the version most often played these days.]

But the kicker, it seems, regardless of song lyrics or censors, the one that makes me wonder what was I thinkin’? How could I not have known my life was solidly in Jim Crow, when I lived, at the corner of Marshall and McAden streets, literally across the street from “colored town”? Where L, our maid, walked home to, disappearing across McAden into the neighborhood where the Graham Colored School housed all those kids I’d hardly ever think about, until the fall of 1968.

As the school year ended in June 1968, so did our Jim Crow lives. Graham High School had had three African American students in the three years I had attended, as North Carolina like the rest of the South continued to stall in the face of imminent full integration, relying instead on the “freedom of choice” promised by the Pearsall Plan. Clearly designed “to legally circumvent full-scale integration,” it was the bridge in North Carolina from Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 to the beginning, in 1957, of another decade of delays in getting beyond token integration. Alamance County Schools held out about as long as it could and hired a new superintendent to get the job done.

Robert Canady had enrolled as a senior when I was a freshman, recruited from Central Alamance, the consolidated school for African-American students in Alamance County, by our basketball coach, Herb Hawkes. I know nothing of what Robert went through that year, but I remember being surprised at how a ball player so clearly the best on our team could so nervously screw up during a game. What I’d have done in a gym full of Black players, fans, and referees, with me the only White boy there, I never contemplated, can’t imagine; but at practice, when it was just us, jayvees and varsity running scrimmages, he was always a show, always the strongest rebounder, impossible to stop on a drive to the hoop or with a quick pull-up jumper kissed softly off the glass. At any rate, he graduated, and we were all White again the next year.

Then, junior year, two brave young women, Brenda Foust and Jessie Warren, transferred from Central to attend Graham High for their senior year. Of their treatment, I remember little but for the mean graffiti that would show up on walls from time to time. It would be many years before I’d begin to wonder what must have gone on to get Brenda and Jessie to embark on this perilous adventure: were there other kids considered for this “honor,” and did they opt out–what threats might have been made here, like throughout the South when White communities felt threatened by Blacks wishing to vote or go to an integrated school? Why were none selected for the previous year, when, after Robert, we reverted to an all-White school? What kinds of deals and promises, made or broken? Under the list of “senior accomplishments” in our school annual that year, both were noted only for their “transfer from Central Alamance, 4,” their previous years of accomplishments disappeared completely. Did they refuse to fill out the senior stats form—what would become forever the record of what we’d done of significance as high schoolers (assuming being in Science Club or on Tennis might be considered “significant”)? Were they even asked to do so? Might a dilemma unearthed here be why our senior year annuals had no senior stats?

That annual, The WAG, was named for William A. Graham, North Carolina’s governor from 1845-49, and, of course, our town’s namesake. Before 1968-69, our school newspaper was the Cracker. After federally mandated integration, we changed the newspaper’s name (not while Robert, Brenda, and Jessie attended), but not the annual’s. None of our history lessons mentioned that William A. Graham owned three plantations in Hillsborough that were built and run by enslaved people. Nor did we learn about Wyatt Outlaw, the freed slave, Civil War veteran, and businessman who, early into his second term as a town councilman, was kidnapped from his home and marched at gun-point to the courthouse where he was lynched by local Klansmen on February 26, 1870 for the crime of being “mouthy.” Or William Puryear, who disappeared after inquiring about the murder—his body, bound and weighted, found in a mill pond. The Kirk-Holden War, which arose from these events, was glossed over in history class as the messy end to the bad days of Reconstruction. No mention of that lynching and the countless acts of “scourging” that prompted Gov. Holden to order troops to Alamance and Caswell counties to control the insurrection fomented there by leading White citizens. Holden, subsequently impeached and removed from office in 1871, was seen by us White kids at GHS as a bit of a traitor to the Cause who got what he deserved–clearly the narrative we were supposed to have internalized growing up. The lead attorney for the state in prosecuting Holden’s impeachment? William A. Graham.

We had no doubt been in school with descendants of those who’d participated in our local atrocities, but whether during our senior year we were also in school with descendants of their victims, I did not know–until I started asking.

Outlaw’s widow and their three small children moved to another part of the county soon after he was murdered, but by 1880, Wyatt Outlaw, Jr., and his brother, Julius, were back living in Graham. But it doesn’t take long in today’s searchable world to find familiar names among the dozens of others whipped by White men between 1868-70 trying to preserve their threatened way of life, to learn that also murdered were Robin Jacobs, killed on May 13,1870, by Klansmen pursuing a young teacher who got away, and North Carolina Senator John W. Stephens, garroted in the basement of the Caswell County Courthouse, and the names, too, of dozens of others, Black and White, whipped and threatened, sometimes their homes torn down or emptied of their contents, their children made to watch or if big enough to “help.” James Boyd, a former Klansman, estimated in his testimony at the Holden impeachment trial that between 150-200 whippings occurred in Alamance in the two-year reign of terror that didn’t end until Holden’s militia arrived in Graham.

Among those numbers: Albrights named as perpetrators but also as defenders of those being terrorized, sometimes being threatened themselves, as well as Albrights among the lists of African Americans who were assaulted, and links back to classmates that make of my childhood landscape a kind of haunting.

Prior to attending our 40th high school reunion, I reviewed some of our Class of ’69 memorabilia, including the “Class Will” in which various of us bequeathed certain objects, traits, or observations to those being left behind. One of us Crackers had written but I had long ago forgotten, “I leave this building to the Klan, to burn it down like should have already happened.”

At our 50th reunion, two of our African-American classmates showed up, cousins D and M. My wife and I were seated with them; I had been in a couple of their classes, and knew M a little better: elected president of Central’s student council for the 1968-69 year, before we knew we’d be integrating, she became vice-president at the new integrated Graham High—somehow it had been determined that I, the president-elect from the old, segregated GHS, would take that title to the new GHS; Central would get the VP but lose its name as well as its facility (and most of its faculty), which would become the “new” GHS. In our conversation, I learned that the annual Central Alamance High reunions were never class specific like ours, but were for all that attended. For many of those students, it was almost like [White] Graham High had hardly been a part of their lives, was instead a blip that marred but a small portion that was then for the most part forgotten, as much as possible. The Central kids, I learned, had been told that all their school’s sports records were ordered destroyed by the county upon integration. Neither knew if anyone might have held on to some of that history, and I wondered for the first time about Robert Canady’s former Central team that he’d left behind, to integrate GHS, how their season had gone without one so good as he.

A novel might strain its credibility here to have enter as a late arrival to this reunion scene the fellow who, back in 1969, had willed our school to the Klan, who’d find the only available seat at our table and take it with a casual nod. Our narrator would then wonder silently if the two classmates he’d been chatting with knew that this was the one who’d left that bequest, or if they remembered it at all, and what else might they remember that had slipped so easily past your blithe narrator back in the day, what else so much more visceral and memorable than a line of type that wished upon a building the wrath of the Klan? Regardless, that part of the evening where we’d danced around our memories ended abruptly, replaced by small talk.

D and M excused themselves before dessert.

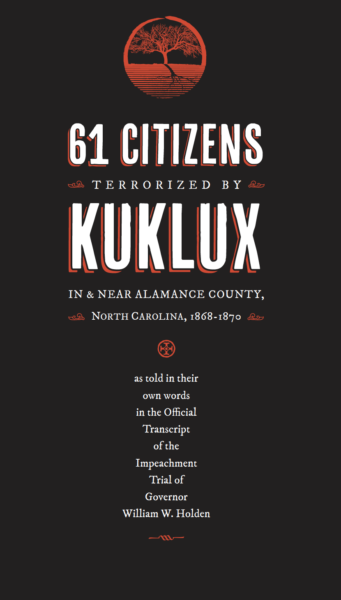

Lots of folks in Alamance County now know who Wyatt Outlaw was and how he was murdered at the county courthouse in downtown Graham by a mob of locals on February 26, 1870–the BLM summer of 2020 has made sure of that historical lesson. Sometimes missing are added contexts: the fake news accounts of how Outlaw had it coming for any number of made up acts of violence, how the 18 participants were eventually identified and indicted, four years later, their charges dropped. Trial transcripts from Gov. Holden’s impeachment make clear the connections between the lynchings, the impeachment conviction, and the amnesty granted in 1874 to all for crimes committed as members of “secret societies.” The impeachment transcript includes horrific testimony from 36 African-American residents of Alamance and Caswell counties who were brutalized by Klansmen from 1868-1870, including the haunting detail that one of Outlaw’s children was screaming “Oh, Daddy, oh, Daddy” as the mob bound him and took him away from their home.

Lots of folks in Alamance County now know who Wyatt Outlaw was and how he was murdered at the county courthouse in downtown Graham by a mob of locals on February 26, 1870–the BLM summer of 2020 has made sure of that historical lesson. Sometimes missing are added contexts: the fake news accounts of how Outlaw had it coming for any number of made up acts of violence, how the 18 participants were eventually identified and indicted, four years later, their charges dropped. Trial transcripts from Gov. Holden’s impeachment make clear the connections between the lynchings, the impeachment conviction, and the amnesty granted in 1874 to all for crimes committed as members of “secret societies.” The impeachment transcript includes horrific testimony from 36 African-American residents of Alamance and Caswell counties who were brutalized by Klansmen from 1868-1870, including the haunting detail that one of Outlaw’s children was screaming “Oh, Daddy, oh, Daddy” as the mob bound him and took him away from their home.

The elm tree from which he was lynched was already gone when Alamance County erected near its place on the north side of the court house, in 1914, a Confederate soldier statue who looks up the street towards where Outlaw had lived, his home on a lot now occupied by First Baptist Church, and protesters have frequented the lynching place, both those who want the soldier taken away and those who say that’ll never happen.

In early 2021, the Graham City Council took up a proposal to re-name Sesquicentennial Park, also on Court Square, for Wyatt Outlaw. His great-great grandson, Samuel Merritt, thought the re-naming “a great idea.” His father was Wyatt Outlaw’s youngest child. But growing up in Henderson, Merritt heard little about the crime: “I guess, for reasons of hurt, it was never fully discussed,” he told Kristy Bailey.

At its February 2, 2021 meeting, the City Council unanimously denied the proposal and suggested that proponents of honoring Outlaw take up a fundraising campaign to finance such a memorial and the procuring of the land on which to put it. Meanwhile, the county has erected an iron fence around its Confederate, who now resembles a prisoner of war more than a sentinel on the lookout for Yankees.

Before the fence was installed, the county had “relied on portable barricades and round-the-clock surveillance to protect the 108-year-old tribute to local residents who fought for the Confederacy.” The 8′ Impasse II Gauntlet Ameristar steel fence was installed in April 2021; it cost “at least $32,100,” Thomas Murawski reported for the Alamance News. On July 4, 2022 a suspected drunk driver crashed his pick up truck into the fence at 4:36 a.m. Video footage shows the truck stayed on the scene for 12 minutes, with “various other drivers appearing to stop to ask if the (White) driver of the truck needed assistance.” The driver left the scene. Graham police didn’t learn of the incident until it was reported to them on July 6.

Placement of the fencing has also caused concern from NC Department of Transportation officials, who believe that it impedes pedestrian views from a crosswalk and will likely need to be moved to another part of court square, at an unknown cost.

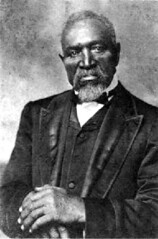

Caswell Holt at 78. Caswellcountync.org/genealogy

While researching 61 Colored Citizens Terrorized by Kuklux in and near Alamance County, North Carolina, 1868-70, I found unsettling answers to inquiries about the local legacy of race violence. One classmate wrote to me, “I remember walking home from school and having to ‘jump’ the side ditch to avoid being run over by a school bus full of White students who were spitting out the window at me. I remember a clerk at the Five and Dime in downtown Graham not wanting me to put the money in her hand. I guess she was afraid to touch me. I however, told her that I would stay there until she held out her hand. I remember the Klan getting word to my father that they were going to burn a cross in our front yard.”

One of that classmate’s relatives was lynched. North Carolina’s poet laureate, Jaki Shelton Green, is, like my father, a Mebane native. Her great-grandfather, Caswell Holt, was whipped, shot, and hanged and let down several times by Klansmen on two occasions. His family keeps a Facebook page in his memory. The great-grandfather of another classmate, who’d taken swimming lessons with me at Kessing Pool, was a magistrate known to be sympathetic to Black complaints about terrorist activities. He was sick in bed when Klansmen came to call; his wife met them at the door with a double-barrel shotgun and the declaration that she’d only be able to take out two of them and wondered which two it would be. They left. That’s a story also told in Durwood Stokes’ book, about the only narrative we ever heard of those awful years. Most of the stories of the 61 Victims whose testimonies I’ve collected are being told in that book for the first time as historical artifacts; that is, they were told and subsequently forgotten, their respective roles in history erased, all the while the stories of their tormenters were rewritten in a great white-washing of history.

This map of lynching sites in North Carolina includes Wyatt Outlaw’s in downtown Graham.

♦

sources

Bailey, Kristy. “Descendant of Wyatt Outlaw Likes Potential Tribute to Great-great Grandfather.” Alamance News. 21 Jan. 2021: 1, 2,7

“City Council: No Interest in Renaming Sesquicentennial Park,” Alamance News. 11 Feb. 2021. 1A

Freeland, David. “Behind the Song: Sam Cooke’s’ ‘A Change Is Gonna Come.'” americansongwriter.com,2019. Web. 2 July 2021.

McDowell, Ian. “Wyatt Outlaw and the white men who put a monument where they lynched him.” Yes! Weekly. 11 Aug., 2020. Web. 21 Dec. 2020. Read it.

Murawski, Tomas. “July 4th early morning crash into fence surrounding monument causes damage at Confederate Monument.” Alamance News 7 July 2022: 1, 3.

Olsen, Otto H. “The Ku Klux Klan: A Study in Reconstruction Politics and Propaganda.” North Carolina Historical Review. 39.3 (July 1962): 340-362.

Stokes, Durwood. Auction and Action: Historical Highlights of Graham, North Carolina. Graham, NC. City of Graham. 1985.

Troxler, Carole. “To look more closely at the man”: Wyatt Outlaw, a Nexus of National, Local, and Personal History. North Carolina Historical Review. 77.4 (October 2000): 403-433.

Williams, Max R. “Graham, William Alexander.” NCPedia, 1986. Web 20 Dec. 2020.

–November 4, 2024

• • •

Publications relating to African-American history, Civil Rights, and integration

book

The Forgotten First: B-1 and the Integration of the Modern Navy. Fountain, NC: R.A. Fountain, 2013. Buy it.

recording

Moonglowers “Live” (1944) & “Pitch a Boogie Woogie” (1947) original soundtrack with liner notes. CD re-issue of vintage recordings, 2015. Buy it.

scripts

“Coming into Freedom: The End of the Civil War in Eastern North Carolina” (one-woman show starring Louise Anderson with the NC Symphony and Badgett Sisters). Writer, producer, director. Creswell, NC: Dept. of Cultural Resources. 1 Sept. 1990.

Boogie in Black and White. (television documentary) Chapel Hill, NC: The Center for Public Television. February, 1988 (writer/producer). Broadcast Feb. 1988: UNC-TV network (Arbitron ratings: 25,000 viewers). Re-broadcast Feb. 1989, UNC-TV; also broadcast on PBS affiliates in 26 states, D.C. and the Virgin Islands. Watch it.

articles

“Langston Hughes Sought Solitude in Reno.” Nevada Magazine, Jan.-Feb. 2019. Read it.

“Mose McQuitty’s Band and Minstrel Days, 1899-1937.” Bandwagon: The Journal of the Circus Historical Society 60.3 (2016): 6-47.

“Jim Grimsley Gets Schooled.” North Carolina Literary Review 2016 online: 32-35. Read it.

“Classic Blues under Gigantic Tents.” Living Blues 24.3 (June 1993) 46-49.

“The African-American Traveling Minstrel Show” Living Blues 24.2 (April 1993) 36-41.

“Micheaux, Vaudeville, and Black Cast Film.” Black Film Review 7.4: 6-9, 36.

rev. of Segregated Skies: All Black Combat Squadrons of World War II, by Stanley Sandler. Washington: Smithsonian, 1992. North Carolina Historical Review 70.2 (April 1993) 234.

“Mose McQuitty’s Unknown Career: A Personal History of Black Music in America.” Black Music Research Bulletin. 11.2 (Fall 1989): 1-5. Read it.

“Boogie Woogie Jams Again.” American Film 12.8 (June 1987): 36-40.

“Breaking the Race Barrier: The Navy B-1 Band.” Tar Heel Junior Historian 25.3 (1986): 13-17.

“Integration Pioneers Reunite in Chapel Hill,” Raleigh News and Observer. Aug. 3, 1986: 3A

“They Helped Break Navy’s Color Barrier,” Fayetteville Observer. Aug. 16, 1986: 2E.

rev. of I Remember: 80 Years of Black Entertainment, Big Bands, and the Blues, by Clyde E.B. Bernhardt. Greensboro News & Record. Sept. 27, 1987: E5.

Papers presented at scholarly meetings

“Rusco & Hockwald’s Georgia Minstrels of 1926,” Nevada Historical Society, Reno, NV. 7 Jan 2009.

“Behind the Masks: Early African-American Vaudeville,” Mississippi Humanities Commission, Port Gibson, MS; July 3, 2006.

“Understanding Vaudeville: Early Black Entertainers, Their Roots, and Their Influences on American Entertainment.” NEH Summer Institute Behind the Veil: African American Life in the Jim Crow South. Center for Documentary Studies, Duke U, Durham, NC: 17 July 1991.

“Boogie in Black and White: (Nearly) Lost Images of Black Entertainers.” (Key Symposium Address) Southern Anthropological Society. Columbia, SC: 20 April 1991.

“Beyond TOBY Time and Shuffle Along: Where the Other Black Entertainers Were.” Popular Culture Assn. Toronot, Ontario, Canada: 9 March 1990.

“Silas Green from New Orleans: Last of the Great Traveling Minstrel Shows.” Popular Culture Association. New Orleans, LA: March 24, 1988.

“‘Pitch a Boogie Woogie’: Text and Re-Text.” Florida State Film and Video Conference. Tallahassee, FL: January 30, 1988.

“Traveling Man: 40 Years on the Road with Mose McQuitty.” Popular Culture Association. Montreal, Canada: March 28, 1987.

B-1 reunion front row L to R: Huey Lawrence, Calvin Morrow, Richard Jones, Robert Brower, John Mason. Back row L to R: Simeon Holloway, Wray Herring, John Gilmer.

B-1 historical marker installed in Chapel Hill – May 27, 2017