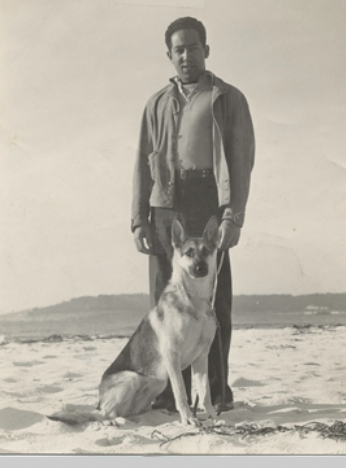

Langston Hughes and Gretta, Carmel-by-the-Sea. Photo by Noël Sullivan. Noel Sullivan Papers, Bancroft Library, UC-Berkeley

Langston Hughes in the Western U.S., 1932-1934

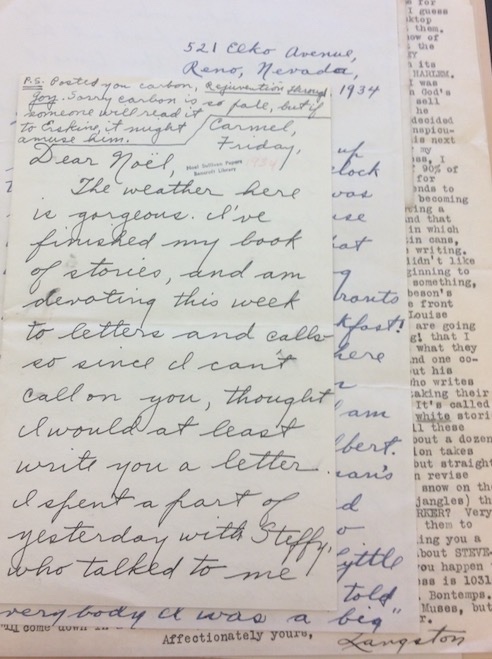

Researching early African-American vaudeville in Nevada, I came upon the intriguing story of Langston Hughes’ extended stay in Reno during late 1934. Details in Hughes biographies were sketchy and contradictory, I found, but several primary sources looked promising, especially the Langston Hughes Papers at Yale’s Beinecke Library. Maria del Mar Galinda, then a graduate student at Yale, helped tremendously with her thorough search through those papers; and at UC-Berkeley, Lisa Monhoff explored the Noël Sullivan Papers at the Bancroft Library for me; Lisa had retired from that library. In Reno, Mella Harmon and the folks at the Nevada Historical Society got me going on local angles. The best of those, however, was furthered by gaining access to Bethel AME‘s history room. That happened by way of my sister, Jane Albright, who was then coaching the UN-Reno women’s basketball team and why I’d started visiting Reno regularly in the late 1990s. Through her local connections, I met Frank Reynolds, a member of Bethel AME, which had moved its congregation and house of worship from Reno to Sparks. Frank had established a local history room in the church basement, where I discovered some of why Oscar Hammonds had been so important in its early history, in several volumes of church records, many of them in his handwriting. Hammonds remains the most obscure of Nevada’s early Black writers–his weather reports, predictions and summaries appeared for many years in most of Nevada’s newspapers, always unsigned. Although I could find no evidence of Langston Hughes having attended Bethel AME, I can’t help but believe that he did so, given his Reno residency in the home of one of the church leaders and his fondness for attending and presenting programs at Black churches during his travels.

Today, the original Bethel AME and the home where Hughes stayed with Mrs. Helen Hubbard are among the few Reno buildings that were there in 1934. I thought Hubbard’s house was gone, but local historian Alicia Barber set me straight on that and saved me from several rabbit holes that had led to wrong assumptions. Her corrective notes confirmed several critical elements of the Hughes-in-Reno narrative, especially as related to the Nixon House, the Chestnut Street Arena, and the club that Hughes most likely used as a setting for his story “Slice ’em Down.”

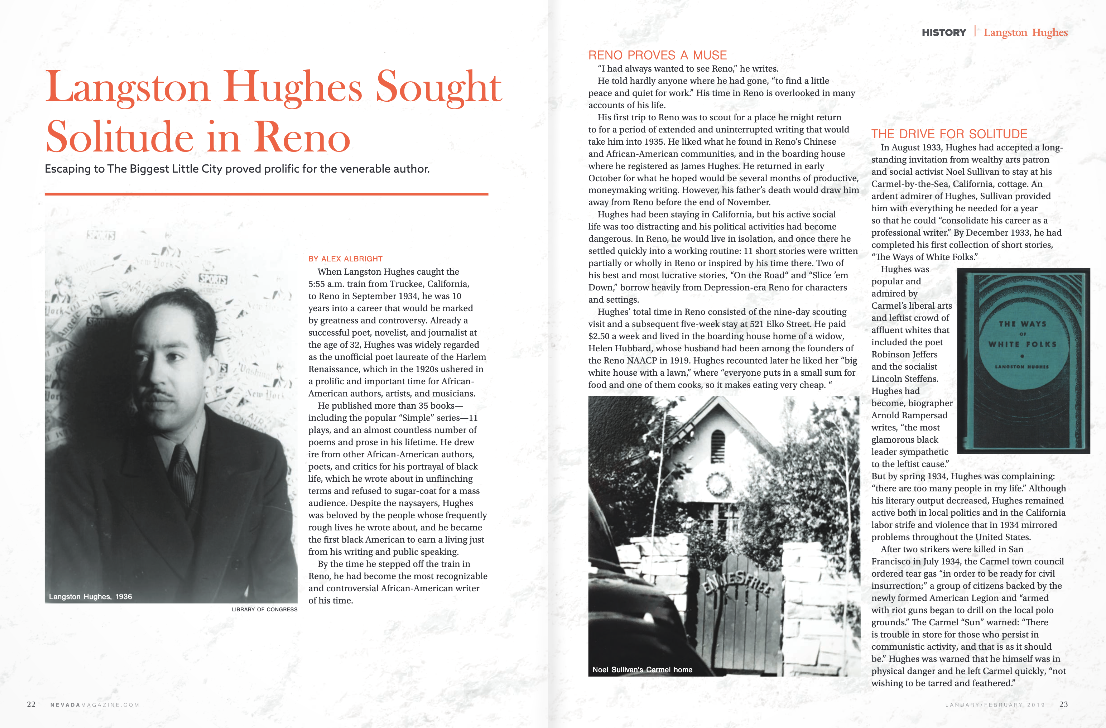

This on-going project has produced so far but one publication, “Langston Hughes Sought Solace in Reno,” for Nevada Magazine in 2019, but it also helped spark an upcoming show at the Nevada Museum of Art, When Langston Hughes Came to Town, which will run from May 3, 2025 – February 15, 2026, and these webpages. I developed the Hughes-in-Esquire page while researching the article, and the Hughes in California and Nevada timelines to support the museum’s show and its curator, Carmen Beals, in its early development. As this research progressed, I visited both the Yale and UC-Berkeley collections–at Bancroft, an unidentified photo of Hughes with Noël Sullivan’s dog Gretta was in a fat folder of pictures marked “miscellaneous”–which helped with further contexts, especially as related to Hughes’ immersion into radical causes and eventual retreat from them, and to the under-appreciated Carmel-by-the-Sea arts scene which Hughes enthusiastically joined. The vast and impressive Hughes papers at Beinecke also helped finalize to a certain extent the Hughes-in-New Orleans page, which intersected with several research interests related to the 1930s.

Although Hughes is usually considered a Harlem and New York writer, his west coast associations were important influences; his early ’30s activities in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Carmel-by-the-Sea are sketched in by Arnold Rampersad in his excellent two-volume bio, but he’s so thorough, detailed, and sourced that it’s not difficult to use his work as roadmaps towards more information. This was especially true as I explored Loren Miller’s importance in Los Angeles.

• • •

That Hughes is most often thought of as a poet is understandable, given his importance to the Harlem Renaissance as its unofficial Poet Laureate and the impressive body of his work. But he was also a successful short story writer, for a time in the 1930s an equal to Hemingway and Fitzgerald in his successes. Reno was important to some of his best stories, and also to a small collection of still unpublished ones written under the name of a white man named David Boatman for the purpose of making him more of the good money he was getting for the race-based stories he was publishing in Esquire.

Hughes often thought of his poems as songs, loved writing songs and also working as a librettist, and a significant body of that work happened in California.

I enjoy imagining how much Hughes would have loved Leyla McCalla’s 2014 CD Vari-Colored Songs: A Tribute to Langston Hughes, and I’m sorry I didn’t discover it until after I’d retired from teaching. There ought to’ve been a lot of freshmen at ECU who knew what this former Carolina Chocolate Drop had done on her amazing record, before BLM came to such necessary prominence. And it’s easy to hear in it again how prescient Hughes was, and how powerful his sometimes seemingly simple verse could be.

article

“Langston Hughes Sought Solitude in Reno.” Nevada Magazine, Jan.-Feb. 2019.

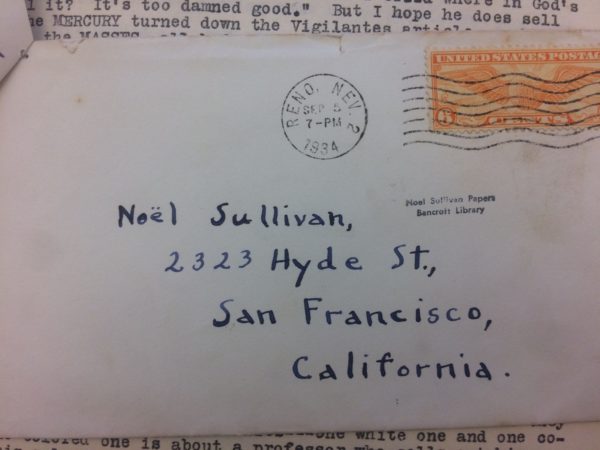

Noël Sullivan Papers, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

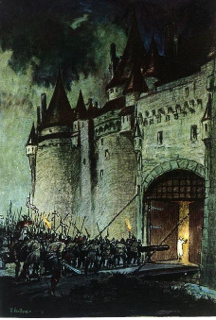

Illustration for “On the Road,” Esquire, 1935

Illustration for “Slice ’em Down,” Esquire, 1936