Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels

Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels don’t get a credit in “Pitch a Boogie Woogie.” The only hint of their role is a mention by emcee Evelyn Whorton of “the lovely Winstead girls.” Rhythm Vet / B-1 bandsman Huey Lawrence knew that they were from Fayetteville, which set in motion the series of events that led to this history. “Pitch ” includes two performances by the chorus dancers from Winstead’s, five women who are also featured in the film’s “Grand Finale,” along with several other dancers. Vocalist and fire dancer Rosa Burrell was also with Winstead’s.

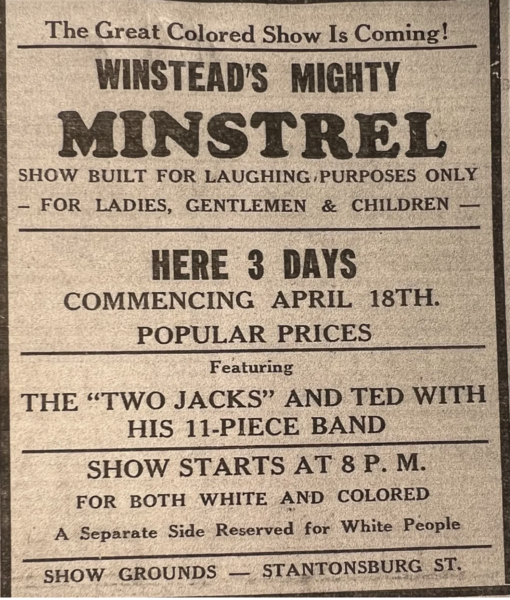

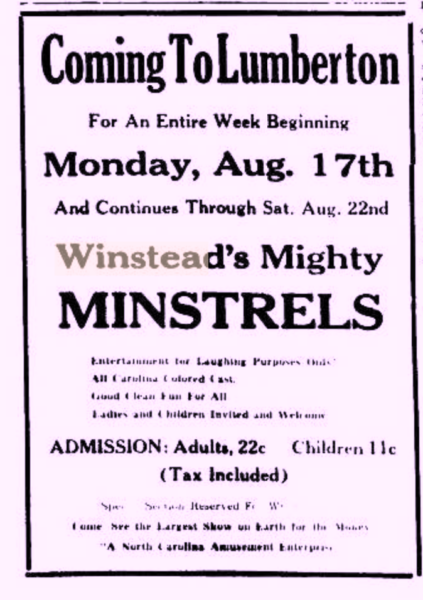

Posted in Wilson, NC, 1940s

Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels was organized as a Black cast tented vaudeville show in the spring of 1931. Through the mid-1950s, they played mostly small towns of the South and mid-Atlantic with a cast sometimes as large as 50 traveling by bus, truck and car. They performed under their own tent on a rented lot, often for week stands, and whenever possible following the harvests of cucumbers, strawberries, peaches, tobacco, and cotton. They always had a band of excellent musicians, many of whom were road veterans of many years travel–like Fountain B. Wood and Mose McQuitty, who were touring by the mid-1890s and whose careers would intersect in several show bands over the decades–and a chorus line of five or six young women. Their comedians and specialty acts were usually a mix of those who’d not made the transition into film, talented veterans whose time had passed, and those whose dreams of being stars would not last, whether from lack of talent or opportunity, or accident. They hardly ever bought ads in local newspapers but advancemen would paper a town prior to their arrival, which they’d announce with a band traveling about town on the back of a truck, recruiting talent and workers to help erect their tent and concession and gaming stands on a site not unlike a circus. Then they’d parade, and prior to their evening’s show (what started in 1931 as a ten-cent show was charging half a dollar admission by the early ’50s), they’d play a mini-concert in front of their tent. Afterwards, a Midnight Ramble!

In fact, most of the operational framework of Black tented vaudeville was circus-derived, and the form established itself as a staple of small-town America through its early associations with circuses: most big circuses had a sideshow that included, along with its human oddities, a “minstrel show.” The show’s offerings were, however, from the first days of the 2oth century essentially revues, filled with dancers, comedians, specialty acts, and accompanied by a band. The term minstrel, however, would haunt it and the memory of its performers, especially those who corked up or put a lip on–see Spike Lee’s 2000 film Bamboozled.

In 1931, however, American popular entertainment was less than two years removed from Libby Holman’s sensational singing of “Moanin’ the Blues” in Blackface on Broadway, and Blackface wasn’t a problem through most of the 1930s. Attitudinal change came rapidly, with World War II and then the advent of television, though even there, it took a few years for Americans to sour on Amos & Andy. And still today, the comedians who dance at the end of “Pitch a Boogie Woogie,” all from Winstead’s show, have the power to offend. To help you keep up, see this list of performers who’ve Blacked up. It doesn’t include William Earl, who was professionally funny in Blackface by 1907. When I first showed “Pitch” to each of them, Mattie Sloan in Laurinburg and Willie Jones in Philadelphia, both excitedly called out his name –“That’s William Earl! That’s William Earl!”–as soon as he came on screen, in the Grand Finale, although it had been over 50 years since they had worked with him.

• • •

E.S. “Fat” Winstead. Courtesy of E.S. Winstead, Jr. Mattie Sloan Collection of Black Minstrel Ephemera. Special Collections, ECU. Greenville, NC.

E. S. [Emerson Stowe] “Fat” Winstead had done a year-and-a-day in North Carolina’s state prison at Raleigh for bootlegging and intended to re-join the Wilmington-based Dr. Robinson’s Medicine Show upon his release; Winstead and Robinson were both White men who would spend their careers owning and managing Black cast shows. Robertson and his band leader, Frank Sloan, picked up Fat from prison, anxious to get back on the road. Two factors led to a name change for their outfit: Fat–not Robertson–bought their first bus, for $50, and there were already a Robinson Brothers Circus and a Robinson’s Silver Minstrels on the Southern tented vaudeville circuit. So they began business as Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels and staged their first show at the Rex Theater in Raleigh.

Mattie Sloan, left, with Viola Harris, outside Winstead’s tent, 1930s. Mattie Sloan Collection of Black Minstrel Ephemera. Special Collections, ECU. Greenville, NC.

The ticket-taker at the Rex that night was a young woman from Laurinburg who’d gone to Raleigh to attend college at Shaw but without sufficient funds. Mattie Barber agreed that traveling with a show would be fun, and likely more profitable than her work at the Rex. She would become the show’s ticket-taker as well as an occasional performer, cook, seamstress, talent scout, bookkeeper–and Frank Sloan’s wife.

Sixteen years later, Winstead’s show would be in Greenville, North Carolina, at the same time as Irvin C. Miller’s Brown Skin Models–it’s possible that the two shows were traveling together, or that the Models had been with another Winstead owned show.

In 1986, I wrote an article about the U.S. Navy B-1 band for the Fayetteville Observer, targeted because three of B-1’s vets were from the area: Richard H.L. Jones, Thomas Gavin, and Willie Currie, Jr.–Jones and Gavin as part of the Rhythm Vets also performed in “Pitch a Boogie Woogie.” Everyone, it seemed, had heard of Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels, but beyond their association with Fayetteville, I had found nothing. So the brief bio appended to my article indicated I was interested in learning about Winstead’s, and within a week, I received a note from Mattie Sloan’s hairdresser, Mary T. Ledbetter. She wrote, “This lady can give you all the information you will need about Winstead Mighty Minstrels.” She’d been listening to Mattie Sloan’s tales from the road for decades as she did her hair and was glad to tell me how to contact her.

I called Mattie Sloan that night, and the next day, August 24, 1986, I drove from Greenville to Laurinburg to meet her for the first time. I would visit her often over the next several years, usually for a few hours of talk punctuated by samples of her cooking, sometimes for a drive to find a cemetery or a lost performer whose address she had remembered. Her stories weren’t always easy to follow, especially in their chronology, but they never lacked for drama, even though they were usually related in a kind of deadpan monotone. You could tell she really knew these people whose names she’d rattle off in quick lists according to prompting, although often they were nicknames, seldom a last name. And instead of where they were from, it was usually where they joined the show. Much of what I learned about Winstead’s has come from her, the contacts she gave me, and the other former performers who worked the Depression years. Some corroboration and additional details come from the Chicago Defender and Pittsburgh Courier. But my more recent research has benefitted greatly from the internet beyond the amazing online searchability of vintage newspapers. Type in the right phrase and the image of a priceless handbill advertising Winstead’s performing in nearby Wilson, 1940s, appears. Was it for shows in which Sam Lathan would perform?

Mattie Sloan Collection of Black Minstrel Ephemera. Special Collections, ECU. Greenville, NC.

Lathan, who grew up in Wilson, played drums for the Monitors for 60 years–and before that, 3 years on the road with James Brown’s Famous Flames. He was one of the locals who got picked up by Winstead’s truck on the first day of their show there. He credits his work with the Winstead band as teaching him “how to listen to the other performers around me and how to complement what they were playing–not compete with them. That’s really where I first learned to listen.”

Although they wouldn’t meet for over a decade, Monitors’ co-founder Bill Myers had a similar experience growing up in Greenville, on the Block. He recalled working with Winstead’s band, led by Fountain B. Woods: “I was playing sax. We’d get on the back of a truck and drive around Greenville–we’d go to different sections of town–and then we’d go out and play in front of the tent. I Learned the importance of listening from Winstead’s, and then to play in harmony next time he does that same statement.” He was a student at Eppes High School then, in bands led by B-1 bandsmen Richard H.L. Jones first and then William Gibson. Had he been older, he might well have gone on tour with Winstead’s, as Diddy–a Bonners Lane neighbor who played with Winstead’s for several years–had urged. But he got sent home every time before the midnight ramble. “I couldn’t stay for that,” he said. “They wouldn’t let me see what was going on there and I always wondered.” Myers was not the first to tell me, Whites wanted to come to the shows, too. So they’d have Whites on one side Black on the other, and as things got hot, they forget that rope, folks go under the rope and then the police come to try to stop it.”

• • •

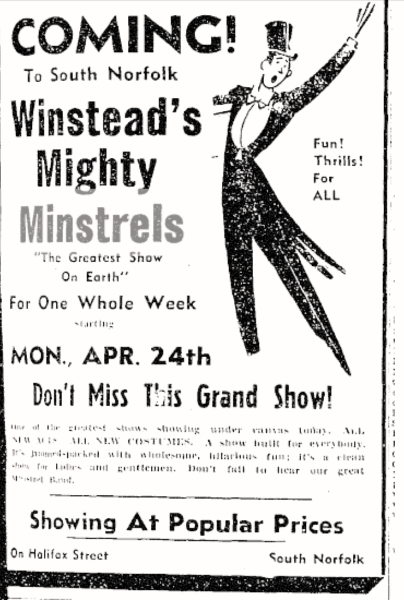

Norfolk Journal-Guide, April 24, 1944

After their Rex Theatre debut in 1931, the newly formed Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels left for Wilmington, setting out to establish a traveling tent show that would rival Silas Green from New Orleans, which seemed to be making for its owner a small fortune, judging from all the press accounts of his travels to Cuba, New York, and Chicago, vacationing and checking on new talent. Mattie Barber joined the crew, which included Robinson’s wife, Margaret; two chorus girls–one who doubled as contortionist; Sloan and the band; and Mattie, soon to be Frank Sloan’s wife. With Frank Sloan as band leader, they were assured of having first-rate musicians and entertainers. He had been playing tenor sax with some of the best Black traveling bands in the country since the late 1910s, including Ma Rainey and the legendary but unrecorded P.G. Lowrey, and his connections would serve them well in recruiting performers, musicians especially, left jobless by the Depression and then the parallel growths of the movie and recording industries.

Robinson and Winstead argued and split up in Salisbury, Maryland, Mattie Sloan recalled. Her future husband went with Winstead and became his right-hand man–stage manager, band director and talent scout–and his reputation in the music world would prove the basis for much of Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels’ regional renown as they toured for 25 years, much of it successfully, even during the worst of the Depression. For whatever reasons, Winstead seems to have flourished, and he often operated a second and sometimes a third show.

According to his son, Winstead was from Marion, Tennessee, but he didn’t know how he got to Fayetteville or when, or how he met his mother, Helen Garnett McCordendale. Winstead, Jr. was three when his dad died, in 1943. “They called him Fats,” he said. [Mattie Sloan omitted the ‘s’ when saying his name.] “And he weighed about 320 pounds. He bought a brand new Buick Special every year. People said when he’d drive by with his arm resting on the window it would look like a sack of flour. Mom had a special coffin made for him, and it cost $5,000 for the funeral. It had a glass shield over the top and it was vacuum sealed, so his body could be exhumed and you could wash him off with alcohol and he’d be preserved.” Winstead, Jr. said almost all he knew about his dad came from others’ accounts: “Apparently, he was quite a character. He used to love to shoot craps, but he had to unbutton his shirt half way down when he squatted down so he wouldn’t rip the buttons off. He wasn’t a drinking man, but he carried a pint of Four Roses in his glove box because he was concerned with having a heart attack., which is eventually what killed him.”

Winstead, Jr. said that his dad “was very wealthy at the time,” and explained: “He bought a lot of property. He built a lot of houses; he’d buy up whole blocks at a time, with houses or without, and he’d rent them out, like low-income housing. And wherever he stopped with the group, he’d deposit the night’s earnings in the local bank. When he died, Mom didn’t know about it. But I suppose all the accounts have been absorbed by the state long ago. After he died, Mom fell into a drinking thing.”

Winstead built a motel on US 301, near the site today of the Crown Coliseum. “There was ample acreage back behind it,” Emerson, Jr., said, “and that’s where they kept their stills. A lot of entertainers came through and stayed at our motel, too. They’d spend weeks there. There’s still an old tree where our motel was. One year, I was about 5, I got a ram for a present and I tied him to that tree. Next morning he was gone, broke the rope and ran off. Mom ran the motel till 1947 and then sold it.”

Mattie Sloan explains Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels to a tv crew, 1988.

• • •

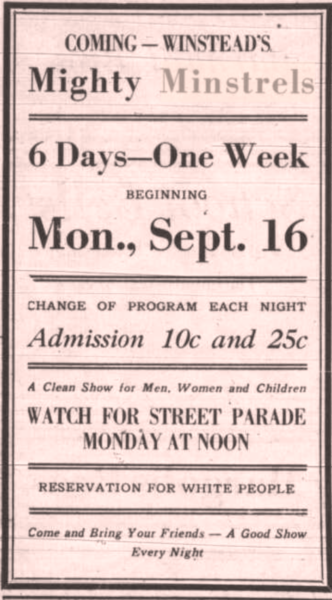

Williamston Enterprise, Sept. 13, 1935: 5

That first performance at the Rex in 1931 was barely a show, Mattie Sloan said, but it was a beginning: “We added some actors as we went on. We played week stands and we always had an amateur show on Thursdays and we could pick from that. You’d get some good actors, some real good dancers. but most of ’em weren’t professionals. They’d go a few towns and then get tired and go home.”

At full complement, Winstead’s would travel with about fifty people–one year they boasted of 61. Although his salaries were less than what might be made on Silas Green from New Orleans, he kept his shows on the road, paid regularly, was good for loans, and he would always make sure your body got home for a proper burial if you died on the road. It wasn’t unusual for him to pick up performers who’d been stranded on the road, and he rescued Irvin Miller’s shows more than once, keeping some in his cast and making sure others got on their way back to New York.

Many, however, were veteran professionals, though more than a few, like Bessie Smith, were past their prime: Bessie Smith was singing with one of his second shows when she died after an automobile accident in 1937. Others, like bandleader Fountain Woods, Ford Wiggins, and W.C. Davis, had earned solid reputations for their talent and professionalism although they’ve for the most part long since forgotten. Woods and the others who worked on Winstead’s and Silas Green would have had no trouble switching employers, as their performances were structured the same, using a format loosely based on the old time minstrel shows, with an opening, an emcee, who’d bring on two comics, then a band number, and then a series of vaudeville acts interspersed with music and song, a skit, and the two or three numbers by a classic blues vocalist that would lead into an all-on-stage grand finale.

The first documentation of Winstead’s in the Black press that I’ve found is an October 1933 notice that “Winstead’s Minstrels Are Going Good” in the Havre de Grace, Maryland area. By November, they are “perhapsone of the largest companies on the road, featuringf O.W. Mason’s band and J.C. Davis, the singing banjo comedian and comedians Noah Robinson, Arthur Boykins, and Shaky O’Neal.

In May 1935, the Pittsburgh Courier reports that Winstead’s are “busy in Wallace, NC.” This report also offers the only historic details I’ve found of Winstead’s, and they differ from Mattie Sloan’s vvid recollections in accounting for winstead’s origin, opening in July 1933, “having lost only one week since,” and “said to pay the biggest salaries on the road of any show of its kind.” Sloan also tells a very different story than this claim: “The cleanest and most diversified show traveling under canvas.”

In June 1935 Frank Sloan and his band “feature daily, playing the Staunton, Va. area, and in August, Virginia Jones reports they are “the biggest hit on the East Coast” with Ford Wiggins and Frank Keith added to their “bunch of stars.” In October, they continued “to knock ’em cold” in around Henderson, NC, Wiggins and Keith starring.

In August 1936, Winstead himself reported to Bob Hayes that they were having “the greatest season,” with J.C. Davis directing and Frank Sloan leading the band and a stage show that included three trick bicyclists: Chief Iron Hand and Joe Green and his wife. In September they were “causing the SRO sign to be hung out at each stop” in North Carolina. In October, Frank Sloan was directing their 11-piece band, with eight chorus dancer, five comics, four tap dancers, two blues singers, and “many other artists” as they traveled in the Laurinburg, NC area, Mattie Barber Sloan’s hometown.

The 1941 cast of Robinson’ Silver Minstrel sounds a lot like Winstead’s, and a note that they are playing Florida dates during the winter fits with stage manager and comedian Willie Jones’ assertion that Winstead put his show up in Fayetteville for the winter and took another, sometimes Robinson’s and sometimes the Florida Blossoms, to Florida.

In May 1943, Winstead’s dropped its “resplendent parade” for the first time; a week later the show reported great business during a 3-day run in Rocky Mount, NC, with 50 in the cast, featuring the Bryant Sisters. They continued “doing record road business” through the eastern North Carolina towns of Greenville, Washington, Belhaven, and Goldsboro, and by the end of May, they boasted a cast of 63.

News reports thereafter disappear, but Mattie Slon’s payroll and routebooks confirm that the show ran into 1956.

The collected history of Winstead’s Mighty Minstreals on these pages is constructed as much as possible from notices in the Black press of the 1930s and ’40s, but the lack of notices during several years when it was touring makes the constructing of a comprehensive roster of performers impossible. I was fortunate to meet a few who performed with Winstead, and others who recalled their shows and some of their bandsmen and performers. But it’s mostly my conversations with Mattie Sloan in the late 1980s and early ’90s in her Laurinburg home that inform this history. Her memory was sharp and her details vivid, but what can I say in the end if, after I showed up at her door in 1987, she got some dates from such a life as hers confused–when we talked, was it 56 or 54 years ago that she had joined up with Fat Winstead and embarked upon her most amazing life on the back roads of the South? She had other routebooks, she said, and salary books, too, lost along the way, but those that made it through the years are now at East Carolina University in the Mattie Sloan Collection of Black Minstrel Ephemera.

–22 July 2025

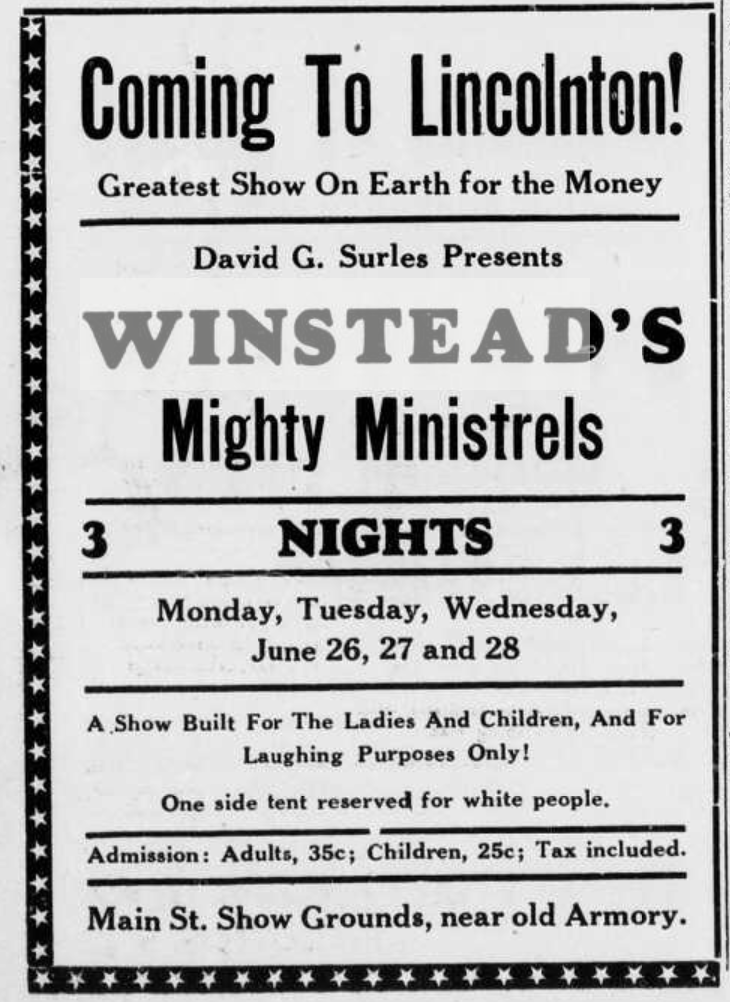

Lincolnton Enterprise, June 26, 1944: 6

Sources

Abbott, Lynn and Doug Seroff. Ragged but Right: Oxford, MS, U of Mississippi P,

Harris, John. Make the Gig: The Story of the Monitors. Columbia, SC. John Harris, 2024.

Myers, Bill. Personal interview. Wilson, NC. 24 April 2024.

Lathan, Sam. Telephone interview. 2 July 2024.

Ledbetter, Mary T. Letter to author. Ms. Fayetteville, NC 18 Aug. 1986.

Sloan, Mattie . Personal interviews. Laurinburg, NC. 24 Aug. 1986; 18, June 1987; 6 Feb. 1987.

Winstead, E.S. Order. Nashville, TN. Hatch Show Print archives. [1928]

Winstead, E.S., Jr. Personal interview. Fayetteville, NC: 21 Aug. 1986.

Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels advertisement. Norfolk Journal-Guide, April 24, 1944: B-6.

Helen & Fat Winstead. Courtesy of E.S. Winstead, Jr. Mattie Sloan Collection of Black Minstrel Ephemera. Special Collections, ECU. Greenville, NC.

Detail. Advertisement for posting. Mattie Sloan Collection of Black Minstrel Ephemera. Special Collections, ECU. Greenville, NC.

The Robesonian, Aug. 10, 1942: 10

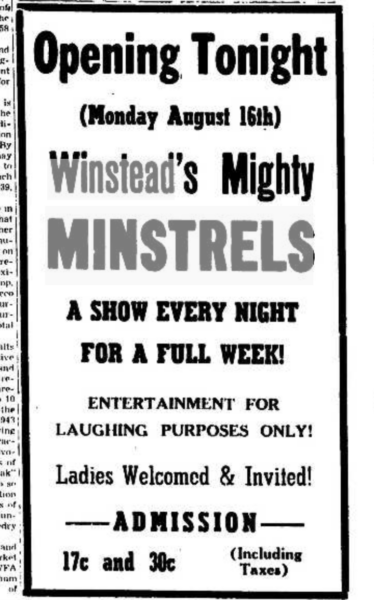

The Robesonian, Aug. 16 ,1943

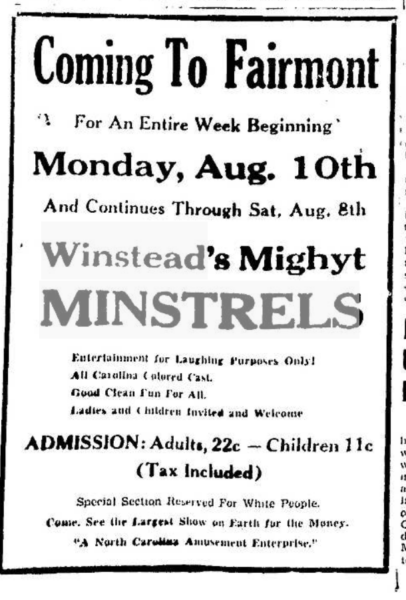

The Robesonian, Aug. 10, 1943, with typo.

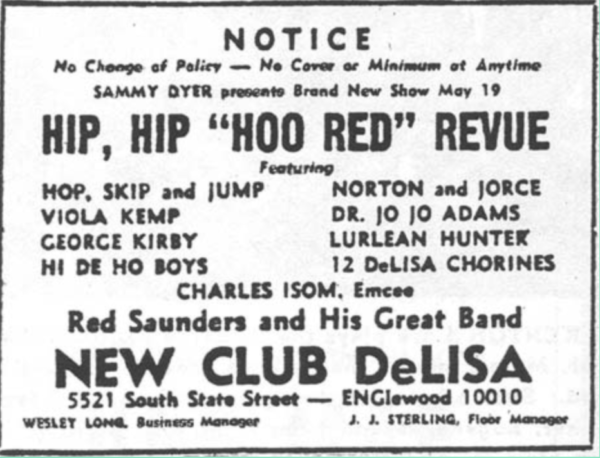

Chicago Defender, Feb. 22, 1947

Viola Kemp joined Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels in time for their Greenville, NC dates in July 1947. She’s one of the featured dancers in “Pitch a Boogie Woogie.”