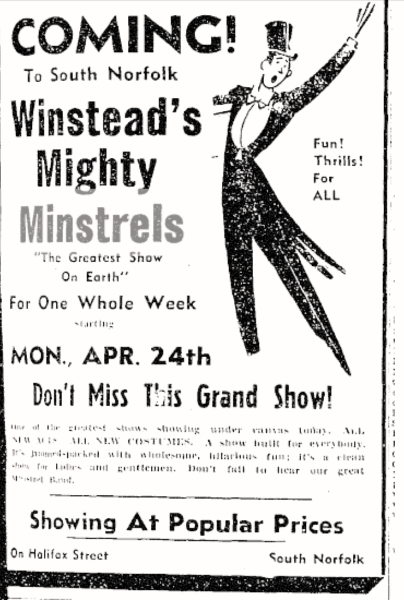

Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels kept an 8-11 piece band on the road for 25 years, from 1931 to 1956 following by truck and car the harvests of crops, primarily in the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia with occasional forays into eastern Maryland and Delaware. “Never Alabama, Tennessee, or Florida,” Mattie Sloan said, because of the expense of licensing. The show kept admission charges cheap–ten cents, with a reserved seat for an extra nickel–and stayed in small towns for several days up to a few weeks when business was especially good. The band was augmented wherever they played by adding talented locals, often boys who were too young to go out on the road. Bill Myers recalls as a teenager playing with them “every year,” which for him, was a few years in the early 1950s, recruited annually to “get on the truck” as it drove throughout Greenville advertising its upcoming shows while searching for talent.

The band’s core would be augmented by other performers when they paraded prior to their show, presenting then a mini-concert outside their tent at parade’s end. The parades were spectacles–platforms for showing off–and their showy style was incorporated into the performance style of many of the best Black college bands in the early 20th century. Traditional parade marches would get a jazz treatment. The pre-show concert would feature two or three popular numbers, and for the evening’s performance the core of the band would be ever-present throughout the show, as accompanists to performers, which might be set put pieces for a specialty act, a chorus routine, or charted songs for a featured singer’s performance, to play bridges between performances, and to put on another mini-concert. If a midnight rambel followed, they’d be the workhorses for an after-show of song and dance performances.

Mattie Sloan is the primary source for details on the musicians; rosters come from her memory and the few records of pay rolls she kept, and from occasional notices in Black audience newspapers. As with most show news, many seem to have been published as submitted, including commons and over-used superlatives. In 1933, they were “perhaps one of the largest shows on the road.” When veteran vaudeville stars Ford Wiggins and Frank Keith joined, in 1935, they became “the biggest hit on the East coast.” Winstead himself called 1936 the show’s “greatest season,” with “SRO signs hung out at each stop during their trip through North Carolina.” That year, the show had an 11-piece band, eight chorus dancers, five comics, four tap dancers, two blues singers and “many other artists.” In 1943, even with several stars already drafted, Winstead’s carried 63 people for its “record breaking performances through [the] Carolinas.” C.E. McPherson (1873-1970), general agent, had been writing and selling songs since 1898 as Cecil Mack.

Mattie’s husband, Frank Sloan, Sr., directed the band for most of its run, and their four children were all raised on the show, joining in the band as soon as they were able.

Musicians & singers

Anderson, Martin. (M.L. )Alto & tenor saxophone. 1933.

He’s known as “Sax Anderson” in one press report. Mattie Sloan said he was her husband’s best friend: “They slept together in cabins.” He had worked on Silas Green from New Orleans with Mose McQuitty. “We saw him in Hamlet,” Mattie Sloan said. “They were taking him to the hospital with t.b.. His fingernails and toenails had grown curved down, he was so bad off. I came up to Fayetteville to bury him,” in 1939. [I once drove around with Mattie Sloan looking for McQuitty’s grave, which she said was in with other actors and musicians that Winstead had buried, somewhere near the block or so of rentals he maintained. No traces where she took us to look, all under new construction and pavement.]

Anderson, Leroy. Chaueffer, canvas boy.

Although he wasn’t in the band, he’s included here because it’s easy to confuse him with Sax Anderson, and also because of this story about him that Mattie Sloan told. She said he was from Philadelphia, and that he came with Po Boy from a carnival and once went back to Philadelpha, a mistake: “They were stone friends. They got up there and Leroy died that morning, Po Boy that night. Both of em drank real bad. Leroy got show by Kemp one. We were in Durham, and he crawled up under a car outside a club there. He was with the show until Mr. Winstead died, then they joined another carnival” before his fateful trip to Philly.”

Brother, Kid. Snare drum. 1933.

Davis, J.C. Trombone, banjo, guitar, vocalist, producer, manager. 1933, 1934, 1935, 1936

Billed as “the singing banjoist,” he played the 1924, 1925 and 1927 seasons with Silas Green from New Orleans, and for the 1931 season he was producer of the Florida Blossoms, “one of the fastest shows ever on the road.” In ’25, “the silver-toned tenor” sang from a pedestal mounted in the audience. In ’34, King Oliver bought his song “Did You Ever Have the Blues?” His wife, Vennie Davis, was with him as a chorus dancer on Silas Green and Winstead’s.

Dixon / Dickerson, W.B. Trumpet. 1933, 1935, 1936.

Mattie Sloan said that he was with the Winstead band from the beginning, along with George Gilliam and Mason, “the best trumpets we had,” and all from Silas Green from New Orleans. Dixon was “on of those Georgia men,” she said, “but he was reliable, though.” She said he left Mazelle for Ruth, with whom he went to Philly, where he worked nightclubs, with her singing.

Dunning, Don. 1941 in Robinson’s Silver Minstrels band, likely a Winstead show; 1947 in “Pitch a Boogie Woogie.” He also led the band for Irvin C. Miller’s Brown Skin Models during the 1940s.

Gillens / Gilliam, George. Trumpet, sax. 1933, 1936.

From Macon, Georgia, Mattie Sloan said that he also played on Silas Green from New Orleans for several years.

Harris, D. “Dee.” Drums, bass drum. 1933, 1936.

In 1933, also listed as “on stage.”

Hooks, Shadow. Brass, 1936.

“He was a fine trombonist” from Macon, Georgia, said Mattie Sloan, “nice, too, but a stone drunk. Buck Nelson took care of him. Dropped dead in a parade in Georgia. We lost five that year in Georgia.”

Hubert, Ted. Tenor sax.

Humphrey, Earl. 1902 – 1971. Trombone, bass. 1933, 1935.

Earl Humphrey, a renowned trombone player, was one of three Humphrey brothers born in New Orleans and taught to play by their grandfather, a famous local music teacher. He played in New Orleans with numerous bands during the ’20s, including those of Lee Collins, Buddy Pettit, Chris Kelly and Louis Dumaine.

He joined the Florida Blossoms in Macon, Georgia, in 1931, “flushed out ” of New Orleans by the Depression, and toured with them for three seasons.

In 1937, he was with the Barnett Brothers Circus sideshow band of 10 pieces.

He subsequenty moved to Charlottesville, Virginia and quit music, but he returned to New Orleans in 1964 after his wife passed, and gradually got back into music, playing until his death in 1971. [Music Rising, Tulane, 2 interviews]

Hubert, Ted. Reeds. 1935, 1936.

Johnson, Johnny. Trumpet

Jones, T.H. Trombone. 1933, 1936.

Jones, Virginia. Blues singer. 1935, 1936.

Mattie Sloan said that she was from Wilson, and worked on the show with her husband, Willie Jones (not the Willie Jones who has an uncredited role in “Pitch a Boogie Woogie”). Her take on “St Louis Blues” was popular, Sloan said, “But it’d tear you up to hear her singing ‘You Going to Need Me.’ She was better than Bessie [Smith] I always thought.”

Sloan said Willie and Virginia Jones were together for 23 years: “He was a young one–she called him her son, said she raised him. All them girls got young men like that, said they trained ’em. They had a comedy act together, too, where they’d sing “A Good Man is Hard to Find” and turn the words around.”

They were with the show off and on for most of its run. After she retired, she became a freelance cook in Fayetteville, where the show had winter quarters and Winstead owned rental properties: “Willie gambled all her money away, though,” Sloan said. “And he got to where he wouldn’t put the cork on, so Winstead had to fire him. He ran off to Georgia with this young girl, made him go to work on a trash truck. Three months later, he was dead. Virginia stepped in front of a car trying to kill herself. Finally died back home in Wilson.”

Kemp. Band

Mattie Sloan said that he stayed with Viola Kemp’s mother, Flossie, and that he shot Leroy Anderson: “Crippled him, too. Leroy craawled up under a car and that’s the only thing saved him. He [Kemp] went to Baltomore and opene up a laundry.”

Kid Brother. Snares. 1933

Lathan, Sam. drums. From Wilson, played with Winstead’s when the show was in town in the late 1940s. He toured with James Brown’s Famous Flames, 1960-63, after which he returned to Wilson, where he raised his family and worked as the Monitors‘ drummer from 1963 – 2024.

Lawston. Saxophone, drums.

From Bennetsville, South Carolina.

Manigo. Band. 1933

Mason, O.W. Trumpet. 1933, 1936.

He was with Silas Green for the 1932 season.

Mason, Charles. Trumpet. 1933.

Both Charles and O.W. Mason are on band rosters for the 1933 season.

Mattie Sloan said that a trumpeter named Mason came “from overseas,” a term I later came to understand meant the Eastern Shore.

McQuitty, Mose. Trombone.

A veteran from the late 1890s show world, McQuitty worked for a Winstead-owned show that traveled as Backer’s Georgia Minstrels in 1935. He retired in Fayetteville, NC, where he lived in a small home owned by Winstead until his death in 1937.

Meschaux, Oliver. Trumpet. 1933.

Also listed as “on stage.”

Miles, Bo. Trombone.

From Macon, Georgia, Mattie Sloan said he was “a stone drunk but he could play that trombone. He died in the back of our bus. He got drunk one night and that was it, somewhere in Georgia”–perhaps one of the five, along with Shadow Hooks, the show lost one year in Georgia.

Moon Mullens.(1916-1977) Trombone. 1933.

It seems likely that this is the same Mississippi-born Moon Mullens who made his name as a jazz trumpeter, but his pre-1937 career is not currently documented.

The Monitors, early 1960s. Myers is 2nd from right. Courtesy of Bill Myers.

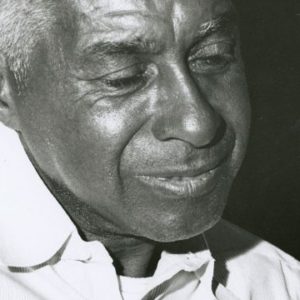

Myers, William “Bill.” saxophone. From Greenville, where Myers grew up on the Block. While in high school, he played with Winstead’s when the show was in town, first recruited by his neighbor, saxophonist D.B. Reeves. A lifelong educator–a multi-instrumentalist band director for decades–he co-founded the Wilson-based band the Monitors and helped establish the Freeman Round House Museum in Wilson.

Nelson, Lamar B “Buck.” Tuba, bass. 1933, 1935, 1936.

From Macon, Georgia, this “progressive young fellow handles the WGW [World’s Greatest Weekly, the Chicago Defender] on this happy bunch.”

Mattie Sloan said his wife, Mary, was an excellent cook and they were on the show “until we busted up” [1955]

Newby, John. Band 1933.

Niece, Walter. Band. 1936.

O’Neal, Shakey. Piano. 1933, 1935.

In 1936, he doubled, co-starring in a comedy duo with Noah Robinson.

Owens. Trumpet. 1954.

Pepper, Julia. Blues singer.

“She sang the blues,” Mattie Sloan said. “‘Oh Child, That Ain’t Right.’ That woman could natural born sing. She was an ugly sister but she could sing”

Pepper, Junior, “Bill.” Drums, piano.

Julia’s husband, he was “a young fellow from Alabama,” Mattie Sloan said. He also sang blues, and with Julia was with the show a little over a year. A “short guy,” she said, he came to Winstead’s from Silas Green from New Orleans. “He would play posts for drums, sit on the ground, spin around. Beat drums on his feet. He’d get paid at night, be broke in the morning.” After Winstead’s, she said, they’d “go ‘cross the ocean and pick peas. Then they’d join the carnies.” [It took me several times hearing Mrs. Sloan use that phrase before I realized “across the ocean” was the Eastern Shore, usually of Maryland.]

Price, Walter “Buster.” Drums, 1933, 1936.

“He loved to eat fish,” Mattie Sloan said. “I cooked fish every other day for him–I called him Fish. Sloan thought I was dating him. He wouldn’t drink, but he’d eat fish. He carried me to a house in Virginia, they had ladies dancd with the snakes, everything. Martinsville it was. They had the dogs with ladies, down in a basement. All we had was coke colas. They had young girls in there, doing these sex things. He was from Richmond. He was with the show forever and ever. He’d go home sometimes to his step mother. Never married. Best drummer in trhis part of the country, but he wouldn’t go north. He could’ve went to New York and made plenty of money but he wouldn’t go. He was like me, we just didn’t like the North. He was still in Richmond last I heard, corner of 4th street and something.” She also said Sloan had known him from before Winstead formed, and that he stayed with the show all his life, until he retired.

Reeves , D.B. Saxophone. 1954 & earlier

Bill Myers recalled him as Diddy, and as an excellent tenor saxophonist and longtime member of Winstead’s band, who was on the road most of the time. Reeves got Myers his first job with Winstead and encouraged him to go on the road with them, although that never happened. During his breaks from the road, D.B., who was a Bonners Lane neighbor of Myers’–played in local bands and often asked Myers to sit in with him, which he was always thrilled to do..

Mattie Sloan’s payroll book for 1954 lists D.B. Reeves and family as employees of the show but adds no other detail, except that D.B. was by far the best paid bandsman.

Robinson, Noah. Band 1933, 1936.

Also listed as “on stage.” In 1936, he co-starred on in a comedy duo with Shake O’Neal.

Sloan, Frank. (1888-1969) Sax, clarinet, band leader & music director, manager. 1931-1956.

He told Mattie Barber Sloan that when he was 12, he and a girl named Hazel ran away to join the Ringling Brothers Circus and that he learned saxophone while traveling with them. He had been in embalming school in Winston-Salem, Mattie Sloan said. “Their parents looked for them for two years, couldn’t find em. So his parents let him go. They said he filled the house with dancing whenever he was hmoe.” For the next 20 years, he played with various bands and shows throughout the South and East, including A.G. Allen’s Minstrels, the Robinson Brothers Circus, Sparks Circus, and Downing Brothers Circus, years of experience and connections that helped him keep Winstead’s a top-notch band. “He was with Mahalia Jackson,” Mattie Sloan said, “when she sang the blues, before she went to the gospel.” He was the show’s only band leader although bigger names would sometimes be announced as such. He also played piano.

He’s mentioned regularly in Black press notices on Winstead’s during the 1930s. Mattie Sloan had in her collection a business card for Smiling Billy Steward’s Alabama Serenaders, traveling with the John Robinson Circus, that listed Frank Sloan as one of two saxophonists in their 8-piece band. Trumpeter Steward led both the band and the show, which included comedian Claude Dickerson, who would also work with Winstead’s.

Sloan, Mattie Barber. Band, management, support staff, 1931-56.

Mattie Barber married Frank Sloan in 1935. She said: “I was ticket seller, I sold tickets and kept the books, and I ran a cook house, and I ran a little joint there, where I sold popcorn and stuff.” And when needed, she filled in on drums, piano, saxophone or organ.

She and Frank Sloan had four children. “My children was born and raised on the show,” she said, “and they all taken music–their daddy gave ’em music, and all of them played in the band. Frank taught them all in his lap–he started them soon as he could. When the kids got 6 weeks old, I’d go back to the show. I lost 6 boys. When I had Goo, the doctor said he was going to fix me. Mama took care of them till they could travel with me on the show.”

Sloan, Frank Emerson, Jr. (1935-1968) Saxophone, drums. 1937-1943, 1945 -1954.

He was drafted in 1943. He’s listed as in the band and directing the band in the late 1930s and on the 1954 pay roll.

Mattie Sloan said he started marching in the show’s parade at 11 “but we had to put him down as 12. ” She added: “I bought some drums for $15 from a White lady. They were silver, really beautiful. I played them a little in the parades. Frank, Jr. played them till he was about 17. He played in New York later.”

Sloan, John “Goo” Gilbert. (1940-1988) Saxophone.

“Goo wanted to play by ear, “Mattie Sloan said, but Frank wanted him to play sheet music. He started [in the show] at about 6 and he played till we closed in 1956.

Sloan, Annie Helen. b. 1938. Trombone, trumpet.

Mattie Sloan said she began playing in the show when she was 7.

Smith, Bessie. Blues singer. 1937.

Mattie Sloan vividly recalls Smith’s brief run with Winstead’s, her singing as well as her late-night card games with Mattie’s husband, Frank Sloan, and others. When Mattie Sloan tells a story, she does voices differently for each character, and I like to think in this one she’s close to an imitation of Bessie Smith. At the very end of this little narrative, she changes back to her normal explanatory voice as she segues seamlessly into a discussion of gambling on the show, a prelude to how they all fleeced Dr. Robinson one night:

My husband went up to Philadelphia and got Bessie out of pawn. Fellow named Rich [Morgan] ran a cigar store there, and he went off. But Mr. Winstead didn’t like her. They fought a lot. Bessie and my husband used to gamble all day. Mr. Winstead, too. They played tunk. Bessie’d had 15 girls, her and Ethel Waters, and they traveled around in a train car. That’s how Frank knew them, from that show.

First time Bessie played with us, she was making $6-700 a night. She carried a slop jar of money. She got 5% of our gross. When we got her out of pawn, she was dead broke. First thing she did when she got paid was start drinking.

Bessie would drink a little liquor once in a while, but Rich wouldn’t let her do it, her boyfriend? he wouldn’t let her do it. He said he better not catch her doing it.

Her and my husband gambled all the time. Sometimes she say, Come on and go with us, and I say, No, yall go ahead on–I’ll see yall tomorrow morning. She say, You gonna let him stay out all night? I say, He can stay out two nights when that’s his pleasure. I ain’t going to stay up all night long with yall. She said, You can go get in my bed and I said I ain’t going to get in bed with Richard–you crazy? She say, No, I ain’t crazy, you think I’m crazy? I say, I don’t want Rich. She say, No, I didn’t say it like that, but you can go on to bed with him. I said No, Darling–yall go ahead on and plays all the poker you want.

See? He ran the poker game on the show, my husband ran the poker games all the tine, just for people on the show. . .

.

Smith left Winstead’s for work on Broadway Rastus, which Winstead was operating. Broadway Rastus was introduced by Irvin C. Miller in 1924,, and he produced annual updates to it at least until 1928. How Winstead had it by 1931 is not clear, although Winstead and Miller appear to have had a long-standing working relationship prior to their shows meeting in Pitch a Boogie Woogie. in 1947. Mattie Sloan said that Earl Backer was running it when Smith joined.

Smith, Walter, Trombone. 1933, 1935.

Sparrow, Kid. Reeds 1936

Walter, Buster. Drums. 1935.

Waters, Ethel. Blues singer, 1936 [?]

Mattie Sloan said Waters sang with the show for a few dates but couldn’t place the year. From Waters’ autobiography, the most likely period where that could have happened was in 1936, when she embarked on a Southern vaudeville tour with Eddie Mallory’s band. The cast included comedian Daybreak, perhaps Daybreak Nelson, a Winstead regular, and some of Whitey’s Lindyhoppers–one group of these worked regularly with Irvin C. Miller’s Brown Skin Models as well as with Winstead’s, both of whose casts appear in “Pitch a Boogie Woogie.” One of those from Whitey’s and Irvin C. Miller’s, Willie Jones, was Winstead’s stage manager for the 1935 and 1936 seasons. In Waters’ telling, the 1936 season ends abruptly, and she and Mallory travel to Mississippi to visit with his family. The chronology of her life then sort of disappears, until 1939, when she starred on Broadway in DuBose Heyward’s Mamba’s Daughter.

Wiggins, Ford. Drums. 1935.

From New Bern, Wiggins broke into show business in 1913 as a “challenge buck and wing dancer” with Silas Green from New Orleans. In 1016, he assumed the role of Silas in the show’s skits, which he played until 1934. He played bass drum in the shows’ parades.

Williams, Sonnie. Blues singer, from Greenville, NC, managed by John Warner. A May 22, 1948 New Journal Guide ad says that he toured with Winstead’s for 2 years.

Waters, Ethel. Blues singer.

Wood, Fountain B. Trombone. Band director 1941, 1943.

Wood was “a conspicuous figure in the history of African American minstrel show bands,” Abbott and Seroff note in chronicling his remarkable career. In 1894, he was traveling with Edwin F. Davis’ Uncle Tom Company in a cast of 50 that included the Hyer sisters, who were near end of their careers. In 1900, he was with the Georgia Up-to-Dates and in 1901, he led the band for the Geyer-West Minstrels, where he worked with future Silas Green & Winstead bandmate Mose McQuitty.

In 1902, he was with W.C. Handy’s sideshow band on Mahara’s Minstrels and in 1927 led the Silas Green from New Orleans band, with whom he was called “one of the greatest trombone soloists of our Race.” He was recruited–reports don’t say from whom, but he had been living in Los Angeles to take charge of the band, and “immediately replaced the overture at noonday concerts “Bridal Rose” with selections from Il Travatore & Il Guarany.” Wood still had charge of the Silas Green band in 1929.

In 1941 he was band director of Robinson’s Silver Minstrels, likely a Winstead show that traveled Florida during winter months, and included future “Pitch a Boogie Woogie” cast Don Dunning, William Earl, and Winstead regular the illusionist Joe Frazier.

Wright, Bob. Band 1933.

Sources

Abbott, Lynn, and Doug Seroff. Out of Sight: The Rise of American Popular Music, 1889-1895. Oxford, MS. U of Mississippi P, 2001.

Abbott, Lynn, and Doug Seroff. Ragged But Right: Black Traveling Shows, “Coon Songs,” & the Dark Pathway to Blues and Jazz. Oxford, MS: UP of Miss. 2007.

“Frank Sloan and Band Down South.” Chicago Defender 21 June 1933: 10.

Harris, John. “Make the Gig”: The Story of the Monitors. Columbia, SC: John Harris, 2024.

Hayes, Bob. “Here and There.” Chicago Defender 24 Aug. 1935: 7; 28 Sept. 1935: 8; 25 Jan. 1936: 9; 18 July 1936: 10; 1 Aug. 1936: 10; 19 Sept. 1936: 18; 29 Nov. 1941: 20.

Myers, Bill. Personal interview. Wilson, NC. 25 April 2024.

“Southern Breezes.” Atlanta Daily World 20 Oct. 1937: 5.

“Shufflin’ Sam Co.” Chicago Defender 4 April 1931: 9.

Sloan. Mattie. Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels Pay Roll Book, ms. 1954. Special Collections. East Carolina U., Greenville, NC.

Sloan, Mattie Personal interview. Laurinburg, NC. 18 June 1987.

Routes, mailboxes, and announcements in Chicago Defender, Pittsburg Courier, Baltimore Afro-American, Norfolk New Journal-Guide.

Waters, Ethel. His Eye Is on the Sparrow. New York: Jove. 1978.

“Winstead Minstrels Playing Big Dates in the Carolinas.” Chicago Defender 20 Oct. 1936: 30.

“Winstead’s Minstrels Are Going Good.” Chicago Defender 7 Oct. 1933: 9.

“Winstead’s Minstrels Doing Record Road Biz.” Baltimore Afro-American 22 May 1943: 10.

“WInstead’s Minstrels Going Good.” Chicago Defender 9 Nov. 1935: 8.

“Winstead’s Minstrels on Annual Tour.” Chicago Defender 11 Nov. 1933: 9.

“Winsteads Minstrels Score Hit.” Chicago Defender. 12 Oct. 1935: 8.

—June 25, 2025