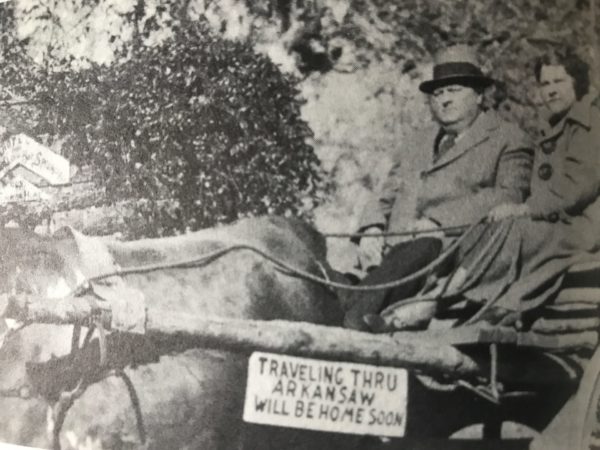

E.S. Winstead, from the Mattie Sloan collection, Joyner Library, East Carolina U, Greenville, NC

E.S. Winstead was principal owner and manger of Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels from its founding in 1931 until his death in 1943. R.L. Surles got possession of the show afterwards, but did not live a year after Winstead’s passing. His widow ran it until it closed about 1956..

According to his son, Winstead was from Marion, Tennessee, but he didn’t know how he got to Fayetteville or when, or how he met his mother, Helen Garnett McCordendale. Winstead, Jr. was three when his dad died, in 1943. “They called him Fats,” he said. [Mattie Sloan omitted the ‘s’ when saying his name.] “And he weighed about 320 pounds. He bought a brand new Buick Special every year. People said when he’d drive by with his arm resting on the window it would look like a sack of flour. Mom had a special coffin made for him, and it cost $5,000 for the funeral. It had a glass shield over the top and it was vacuum sealed, so his body could be exhumed and you could wash him off with alcohol and he’d be preserved.” Winstead, Jr. said almost all he knew about his dad came from others’ accounts: “Apparently, he was quite a character. He used to love to shoot craps, but he had to unbutton his shirt half way down when he squatted down so he wouldn’t rip the buttons off. He wasn’t a drinking man, but he carried a pint of Four Roses in his glove box because he was concerned with having a heart attack., which is eventually what killed him.”

According to Winstead, Jr., their medicine recipe: 5 gallons of white lightning; 1/4 bottle vanilla extract; 6 nutmegs. “They said it would cure anything,” he said, “and I guess you would forget about your ills if you took much of it.”

Winstead, Jr. said that his dad “was very wealthy at the time,” and explained: “He bought a lot of property. He built a lot of houses; he’d buy up whole blocks at a time, with houses or without, and he’d rent them out, like low-income housing. And wherever he stopped with the group, he’d deposit the night’s earnings in the local bank. When he died, Mom didn’t know about it. But I suppose all the accounts have been absorbed by the state long ago. After he died, Mom fell into a drinking thing.”

Winstead built a motel on US 301, near the site today of the Crown Coliseum. “There was ample acreage back behind it,” Emerson, Jr., said, “and that’s where they kept their stills. A lot of entertainers came through and stayed at our motel, too. They’d spend weeks there. There’s still an old tree where our motel was. One year, I was about 5, I got a ram for a present and I tied him to that tree. Next morning he was gone, broke the rope and ran off. Mom ran the motel till 1947 and then sold it.”

E.S. Winstead first shows up in in the entertainment world as manager of A.G. Allen’s Minstrels 1928-29, taking his mail care of Sullivan’s Shoe Shop in Fayetteville. Allen’s was one of the biggest and long-lived of the Black tented vaudeville shows; it’s first years, 1900-1919, are well documented in Abbott and Seroff’s Ragged but Right. After its original proprietor, A.G. Allen, died in Fayetteville on December 27, 1926 at the age of 62 from a heart attack, the Chicago Defender called him “the daddy of all minstrel shows.”

E.S. & Helen WInstead. Courtesy of E.S. Winstead, Jr. Mattie Sloan collection, Joyner Library, East Carolina U., Greenville, NC

Winstead apparently had titles to several shows. Backer’s Georgia Minstrels, Irvin C. Miller’s Broadway Rastus, and Robinson’s Silver Minstrels among them. According to Mattie Sloan, he also sometimes changed the name of a show while it was en route to avoid responsibility for a past event or a troubling incident from catching up with them. “Fat would say ‘That was them other Georgia Minstrels,” Mattie Sloan said. There were, in fact, an untold number of shows traveling as the Georgia Minstrels in the 1920 and ’30s, many of them small shows attached to a circus, wild west show, or carnival.

After Winstead’s death, R.L. Surles took over the show. His widow said, “He had to buy them a bunch of new stuff–things had gotten pretty run down. He refurbished it the next year. It was a pretty good minstrel show. They ran all the way up to Pennsylvania, over to the mountains. They broke down in the mountains one time. Before my husband took over, he’d had some property he rented out. Mr. Winstead had some cottages, too, out on 301 here.”

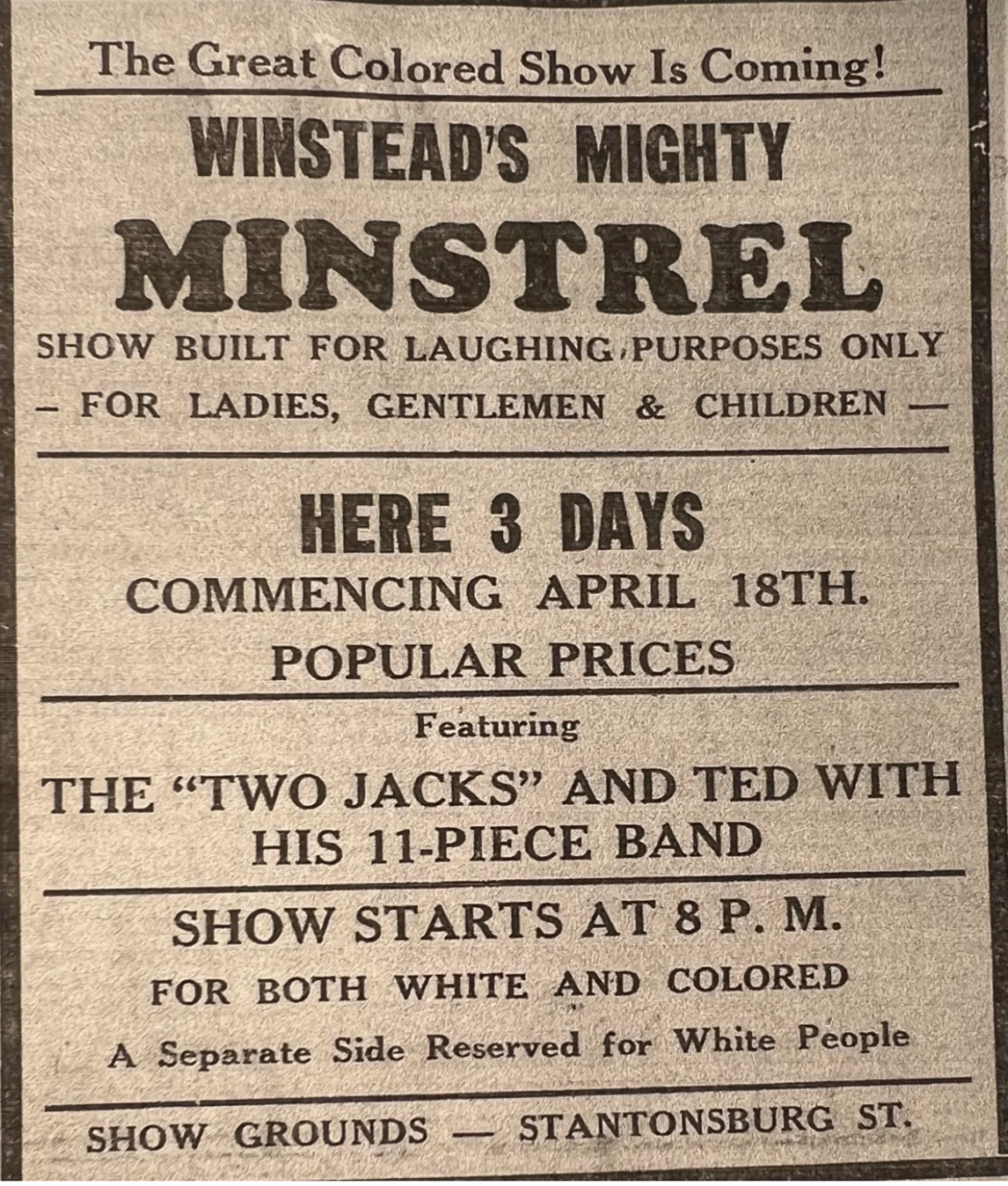

Her memory was that Surles didn’t keep the show long: “That sort of thing had gotten passé. They were up in Washington one time and a bunch of Blacks came out and cut up their tent real bad. Wrecked things pretty bad. They said, ‘We don’t want no minstrels here anymore.’ Wee weren’t used to that, so my husband got out.”

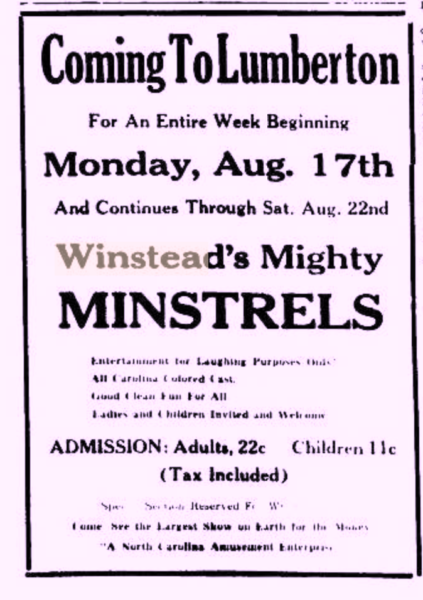

The Robesonian, Aug. 10, 1942: 10

She remembered when Winstead died:

I went with them to Goldsboro. He always packed a tall thing of water and he drank that water all the time. We had some barbecue at one of those famous places, good barbecue. I drove coming back and it was outside of Goldsboro, we turned off on 301, and I said I was getting sleepy, so he drove us on home. After he got to Fayetteville, he went home and lay down and got some pains in his chest. Dr. [R.L] P:ttman at Pittman’s hospital saw him. And he just died. He ate a lot, and he drank that water out of that big white pitcher he kept filled all the time. He could–oh, my Lord!–enough for three people easy. I think that’s what finally killed him, all that eating and the fluids.

She said she didn’t remember the performers, except for Willie Earl.

Evelyn Mitchell told how Winstead got arrested for bootlegging:

My father kept liquor for him because my mother had died and my father didn’t want to give us up, so Mr. Winstad let him keep his liquor–that way he could stay home with us. I was in elementary school, must have been about the 2nd grade. I’ll never forget that day. I came home from school and the police had got them. Mr. Winstead got a year in prison–he was a wholesale bootlegger. We had cases of that stuff in our house all the time, and after he got out, he said he’d never do anything illegal again. He was going to stay straight, so he started the minstrels.

She said that he was “a big man, real big,” and that he “had to have the biggest car made so hed’ be comfortable, so he had a Roadmaster. But he was so fat he couldn’t tie his shoes. He bought them too big so he could just step into them. I remember one time he’d dropped some 50 cent pieces through a hole in his pocket, and they were donw in his shoes, but he couldn’t get them out. So I did, and he let me have them.”

E.S. Winstead. Courtesy of E.S. Winstead, Jr. Mattie Sloan Collection, Joyner Library, East Carolina U, Greenville, NC

Whenever the show was back in Fayetteville, Winstead visited and took the Mitchell family–Eveylyn, her dad, and four siblings–to a local cafe, where’d trea them to hot dogs, candy, cookies. “One night every time he came to town,” she said, “he’d make sure we’d see him. I din’t ever see them after about 1942, though.”

As she got oder, Winstead tried to convince Mitchell to be a dancer. “I wasn’t about to do that,” she declared, preferring not to say more on the subject other than that “they had a woman who taught the dancers–she said she’d teach me easy.”

Of the shows themselves, she said that in Fayetteville they usually put up on Blount Street, “put handbills up everywhere, and played for a week. Her memories of performers were sketchy and select:

I remember this tall slim fellow played that slide instrument, made it sound so pretty. And there was a big guy called Pot Likker, a comedian and dancer. He died o the road and must not have had anybody, cause Mr. Winstead buried hin. He had the body brought on the train. He told me one day they might call and say his body was, and I begged him not to leave for me to answer that phone. He’d brought the suit he bought for him to be buried in and put it on the back porch. I was scared to go out on the porch. And sure enough they called while he was gone and I had to take that message–and I remember a tap dancer named Alexander. They had some pretty girls, real slim, dancing for them. I think they’d open their shows up with the chorus girls, then the comedians and tap dancers. They had their own band–trombone! that’s what it was, and his name was Slim. And Dave, he was the manager of the chorus girls.

Sources

Mitchell, Evelyn. Personal interview. Fayetteville, NC. 13 June 1986

Surles, Mrs. R.L. Telephone interview. 11 Aug. 1986.

Winstead, E.S., Jr. Personal interview. Fayetteville, NC. 18 Sept. 1986.

–4 July 2024

Wilson, NC, 1940s