Irvin C. Miller Girls, chorus dancers

The Irvin C. Miller girls were the chorus line from Miller’s Brown Skin Models, the renowned vaudeville show organized in New York during the height of the Harlem Renaissance as a “sepia Ziegfield Follies.” They continued through the 1930s as a road show, playing theaters throughout the East and South, as vaudeville was being replaced by movies, radio, and big band orchestras, and their chorus dancers were always their primary attraction.

“Pitch” is invaluable in its depiction of typical Models’ stage shows, which featured beautiful young women not so much dancing as offering up various poses through the course of a performance that would be punctuated by specialty acts: vocalists, Lindy hoppers, a fire dancer, perhaps, and comics who’d mix routines with skits–what you get for the most part in “Pitch a Boogie Woogie.” In their three featuresd performances in “Pitch,” the Models do more posing than dancing.

After World War II, such entertainments increasingly were relegated to the rural South, where eventually they folded or, as in the case with Miller’s Brown Skin Models, merged with traveling circuses or carnivals.

Their best years behind them, they may have been working with Winstead’s Mighty Minstrels during the summer of 1947, when “Pitch” was filmed in Greenville. Mattie Sloan recalled their having been stranded in the Carolinas during the ’30s and picked up by Winstead for part of a tour, maybe a couple of times. Willie Jones talked about cast members of Winstead’s and the Models, with whom he was working, almost as if they were interchangeable. He said that the Models had done well during the Depression, but that after the war, work was harder to find, and the New York performers who had worked with them for so many years began leaving the road and returning to New York. Bandleader Barney Johnson was one of those who left, and he was replaced by Don Dunning, a trombone player who had experience playing Black tented vaudeville shows like Winstead’s. He and Jones then began helping Miller re-filll his roster, Jones said, with “carnival people and the minstrel people.”

Willie Jones at home in Philadelphia, 1987. Still from “Boogie in Black and White”

Jones said they were not only cheaper than the New York talent but better entertainers because “they did more work.” He explained: “Anytime you do more work, you get more practice, see. Those people, I found out, it was nothing to do 4, 5 shows a day. They’d change their act more than we would change ours, because they went over the same place sometimes three and four times in one year. And they had to change it every time and for every show. We would go so much farther, we would go p one side [of the territory, from New York to Florida] and come down the other side, and what I did to this place I could do it to another place and another place. I wouldn’t have to change again until the next year. To go down with those people they had to change every week. They may stay in a place five or six weeks, and to keep people coming, they had to put new material in, that’s why they could do it, do so much. See, all those comedians when they come north and went there, they’d beat those northern comedians ’cause they’d know so much stuff.”

According to Jones, a typical Models show would begin with a number played by the band, which was comprised of 7-8 pieces. An emcee would then come on stage for jokes or a song and then introduce the first act, which would be followed by the Models, who, wearing elaborate and revealing costumes, would go through several poses while the band played. “Then maybe a singer,” Jones said, “and the band would play for them, then maybe another specialty act and the band would get a chance to rest. Through all this, the band is in the pit. This is when you close your curtains, that’s what the comedians are for, so you can change the acts and things behind the curtains. They would stand out on the apron and do their show, and then when the comedians go off, they raise the curtains. See, there was a door you go out under the stage and come out on the stage. Then ‘Ladies and gentlemen!’ and the band wasn’t where they were, they are sitting on the stage, not down in the pit.”

The band would then perform its specialty, which would be “whatever was out then,” Jones said, “the song that was a big hit, that’s what people would want to hear the band playing. And the band would have a singer–they could sing the latest hits, see. The real singer would come on with the band.”

From then on, the band was on-stage, performing as the Models posed and as needed with the remainder of the specialty acts, until the Grand Finale, when all came out for a showcase of dancing and posing.

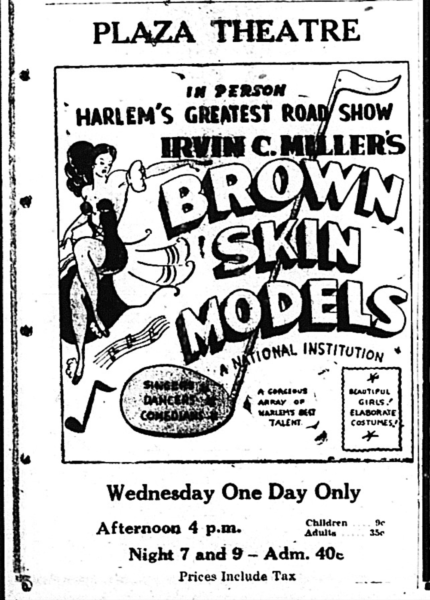

That’s the kind of basic vaudeville show that the Models and others present in “Pitch,” a snapshot of what they did in 1947. How it differed in the 1940s from the mid-1920s Harlem shows, in content and in marketing, may not be knowable. Jones said that some shows he worked were preceded by band concerts; others, followed by a Midnight Ramble, were the most likely to be promoted with advertisements in a local newspaper. Plaza Theater manager Purvis Cohens said the very popular Rambles were basically the same as what one might see at an evening show, that it was “more the idea of it” that brought out a different audience.

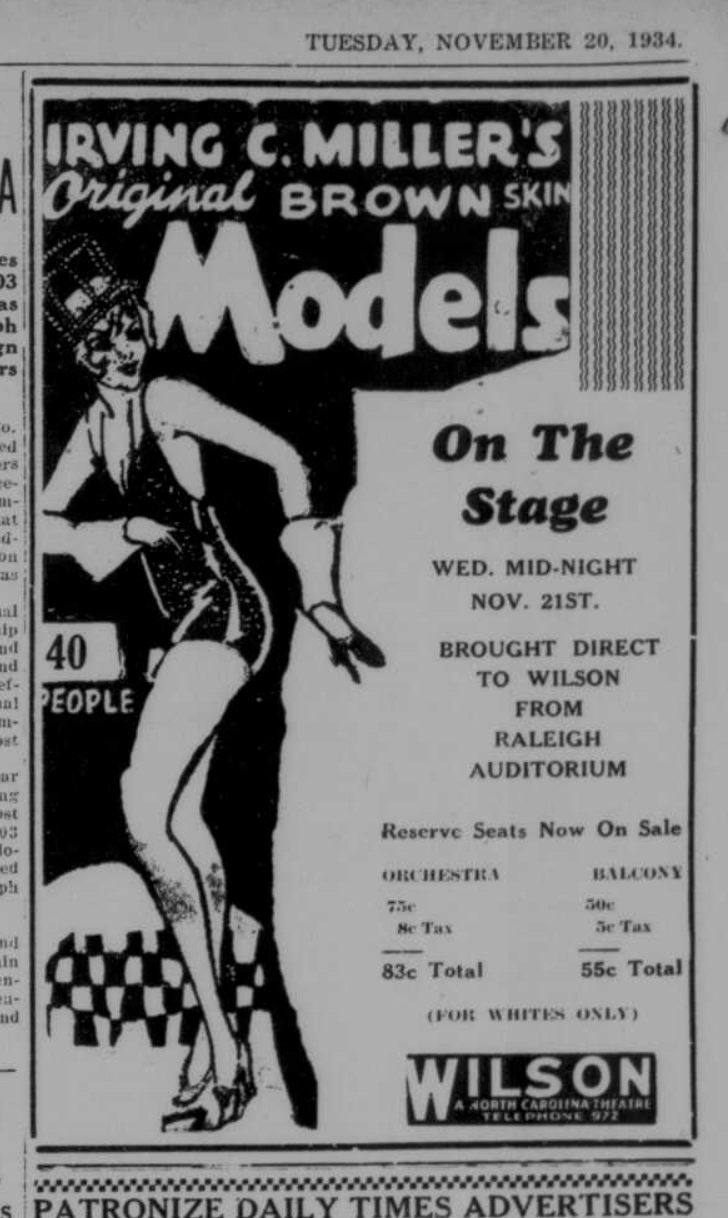

Documenting a show like Miller’s into the 1930s and beyond is complicated in several ways, not the least of which is knowing their routes; those occasional newspaper notices about Midnight Rambles present only glimpses of day & date performances, usually in towns that had become good places for them to play. How those towns are connected, via a series of less attractive bookings over sometimes treacherous roadways, is an unknown story of traveling in the Jim Crow South that’s complicated by the presentation of beautiful dark-complected young women to White southern audiences who, especially at the Rambles, were predominantly men.

Even how the Models marketed themselves seems sometimes at odds. Clearly they were showcasing beautiful young women suggestively clothed: their lobby card was arrested once in Alabama, on suspicion of lewdness; other shows were promoted as having “no course [sic] jokes, no double entendres, nothing the most perfect lady will object to.”

Greenville Daily Reflector, July 24, 1947

I have not found a 1947 Brown Skin Models roster, but in 1949, several in its cast also appeared in “Pitch a Boogie Woogie”: William Earl, Willie Jones, and Evelyn Whorton. The others in that 1949 show may also have been in the movie: Bertha Hayes; comic Clay Tyson, who later would become an Apollo Theater solo star comic himself during the 1950s and then James Brown’s comedian; comic and singer Earl Jackson; dancers Alex and Gracie Shavers; the Three Melody Tones; and orchestra leader Barney Johnson. According to Willie Jones, Tyson and Johnson had left the Models in 1947; both, he said, were in and out of the show during the post-War period.

In 1950, the Models were being billed as “William Earle’s New York revue with Barney Johnson’s orchestra.” Performers included Johnny Moon “and his mule team girls”; Bill Brown “and his dancing nymphs”; Clay Tyler [Tyson?], “new tap dancing find”; the Thunderbolt adagio team; “shapely Dolly Hopson” who dances the Hawaiian rumble, the crab back crawl, the African Jungle Hop,” and an Egyptian ceremonial. Plus: “comedy and a voluptuous prima donna.”

In October 1954, Eubie Blake, Irvin C., and Flournoy Miller were working on a book for a new edition of Models, which opened in Washington, DC before moving to the Apollo for a February 25 show billed as as Irvin C. Miller’s Brown Skin Models of 1955, with Flournoy Miller, Mantan Moreland, Rastus Murray, Clay Tyson, Johnny Christian, the Rhythmaires, and Lee Richardson.

Irvin C. Miller

Irvin Colloden Miller was born in 1884 in Columbia, Tennessee, the oldest son of Lee Miller, a prominent newspaper editor at the Globe. He was educated locally before attending Fisk University, where he excelled at basketball, football, and acting.

After Fisk, Irvin C. went to Chicago to pursue acting and got work at the Pekin Theater, which opened in 1905. He soon brought brother Flournoy and his friend Aubrey Lyles to join him and to work at the Pekin. “The Colored Aristocrats” by Miller & Lyles, their first show there, starred all of them and it introduced the characters who would later be featured in Shuffle Along. Quintard soon joined them in Chicago.

Irvin C. and his younger brothers Flournoy (1886 – 1971) and Quintard Miller (1895 – 1979) were among the most important families of Black vaudeville during the first half of the 20th century. The [Flournoy] Miller & Lyles duo was responsible for Shuffle Along, the 1921 musical that helped launch the Harlem Renaissance. Irvin C. told Jean and Marshall Stearns: “They were the first Negro comedians who could do more than dance. They alo succeeded as writers and actors.”

James Weldon Johnson in 1930 listed Irvin C. Miller as one of “several Negro producers who kept the older tradition alive,” along wiith the Tutt brothers, Whitney and J. Homer, and S.H. Dudley. They had kept Black theatre going during the years it had been “exiled” from Broadway, as James Welson Johnson puts it, a period “which bvegan in 1910 and lasted for sseven lean years.” In fact, Broadway had been mostly White since the late 1890s success of A Trip to Coontown; Johnson acknowledges the importance in the ensuing years of Southernn theaters “where the audiences, on account of the laws separating the races, were strictly colored.” The early 1900s to World War I were the glory years of the Tutts and Dudley and the Black tented vaudeville shows that employed countless entertainers during the first two decades of the 20th century, when opportunities were so limited because of their race. But the “exile” ended gradually; until 1923, Broadway was available for Black productions only during the summer months.

Irvin C. Miller transitioned into the decidedly more modern 1920s as the Tutts’ and Dudley’s influence faded. He produced Put and Take, which followed Shuffle Along in ’21, and in 1923, Liza, “the first Negro show to play Broaday proper during the regular season.” It was “a tuneful and very fast dancing show” that introduced the Charleston to White audiences, although Miller & Lyle’s Runnin’ Wild is credited with popularizing it. Irvin C.’s Dinah, in 1922, was “indisputedly” the first to introduce the Black Bottom on stage, a dance craze that “gained a popularity which was only a little less than that of the Charleston.”

Dance histories are difficult to establish; Marshall and Jean Stearns’ origin-narratives are mostly reliant on oral histories and memories, but they agree that the evidence “for the African origin and early appearance of the Charleston in the South is convincing,” and that the Black Bottom dates back at least to the early 1900s.

During the 1910s and ’20s, the number of duos listed on vaudeville cards with “Miller” as half the billing seems infinite, and without knowing further details about the act it’s often impossible to know which Miller brother is the co-star. Although he is often noted in the Black press for his dancing and acting skill, Irvin C. Miller’s Brown Skin Models remain his most enduring legacy. Their popularity made the chorus line an integral feature of traveling vaudeville; the Models spawned imitators like the Brownskin Mannekins and for over 20 years a regular Apollo Theater chorus line called the Brown Skin Chorus Girls.

The Stearns disagree that Miller was a dancer, stating with only generalized evidence, it seems, that Irvin C. “couldn’t dance a step.” His 1913 vaudeville act with Esther Bigeou concluded with their performance of the “Texas Tommy” dance, and it included his “old man” song and dance.

With his Mr. Ragtime Company, Miller presented an unknown number of original skits and one-acts. A 1916 dispute with producer Leigh Whipper hints at a few of them: First, Miller accused Whipper of having stolen the book for Jake’s Family and re-titling it This Way Out. Whipper responded, “That sketch is as original with Mr. Miller as several of ‘his’ other plays, Mr. Fortune, The Vampire’s Fool, and In Cotton.”

His Broadway Rastus Company was at the Lafayette Theater in New York, with Leon Long business manager, during the same August 1920 week as Quintard Miller’s Broadway Gossips played the Grand Theatre in Chicago, with Long its advance agent. Quintard’s show apparently was having trouble in Detroit, from where “the little brother wired the bigger one a S.O.S.,” which was answered by sending Long to the rescue, “with talent, money, and additional scenery and wardrobe.” Long had apparently been traveling in the deep South presenting “The Ambitious Negro,” a Colored Photo Play.

Beginning in 1926, Miller’s primary focus was his Brown Skin Models but he kept a number of other shows working. In 1928, he was president and treasurer of Theatrical World Publishing, which in April produced The Official Theatrical World of Colred Artists: National Directory and Guide. He was actively promoting Louise “Jota” Cook as a “classique daneuse” in New York and introdcued S.H. Dudley, Jr. as a member of the Models’ staging staff. In additon to the Models, he listed among his productions Tokio; Blue Baby, an All Girl Revue; Broadway Rstus; Desires of 1928,;and Liza.

Miller changed up the Brown Skin Models show as well as its name a few times over the years, and after World War II he operated both the Models and, for a season, the Florida Blossoms Minstrels.

In 1956, Milller scripted Rockin the Blues, an underappreciated gem of early concert films. Parts of it look like an updated “Pitch” with one scene featuring Brown Skin Models-like “dancers.” He’s also credited as a producer for Paradise in Harlem (1939), which starred Lucky Millender and Mamie Smith; Murder on Lennox Avenue (1942), which also starred Mamie Smith; and Sunday Sinners (1939)–all are streaming free on Youtube.

Miller worked the Models and other enterprises out of New York for many years but eventually moved to Philadelphia and then, in the 1940s, to Benton Harbor, Michigan, from where he continued to work in New York, Los Angeles, and on the road until he retired.

He died in 1975.

• • •

Irvin C. Miller theatrical chronology

prior to the Brown Skin Models

1912: Happy Sam from Alabam, a 3-act musical comedy written by Miller and performed with John Rucker’s company opened at the Temple Theater in New Orleans in December. The cast included Miller’s future wife, Esther Bigeou; Miller and another staged the musical numbers. After the Temple, the company moved to the Belmont Theater in Pensacola, Florida for an “indefinite” run. John Rucker had performed in 1896 with Sam Lucas’ Darkest Ameria show. In 1897, with Rusco & Holland’s Minstrel Festival, he “made a marked a sensation” as the Alabama Blossom, who “disports a mouth that a train of cars might well mistake for the entrance of a tunnel and is ‘in it’ at all stages of the game.” In 1898, back with the Darkest America Comany, Rucker was “known all over the United States and Canada as the Alabama Blossom, is incomparable in his new monologue, never fails to receive four encores nightly. His impression of Uncle Amos Jackson, the aged darkey, is absolutely the finest piece of character work seen in our city [Wheeling, Weest Virginia] since the early days of Milt G. Barlow. His make-up is original and true to nature, and connected with his natural ability, places him par excellence as a versatile performer and undisputed star.” In 1910, Rucker’s Down in Dixie Minstrel Company included an afterpiece, “The United Brothers of Possum Catchers” that starred Billy Kersands, and its band included Mose McQuitty.

1913: Miller & Bigeou vaudeville team played the Midwest. Of their extended run at the New Crown Theater, proprietor Tim Owsley wrote that they were “a pretty classy team.” Flournoy Miller and Aubrey Lyles’s production The Cabaret also starred Kid Brown.

1914: Miller and Bigeou’s vaudeville routine included his tango. They joined Kid Brown’s company in Chicago, for which Miller wrote Mr. Ragtime as a “farce comedy,” with Miller playing straight man to Brown ‘s comedy.

1915: .Miller’s Broadway Rastus played first in Philadelphia. His first hit, “it packed theaters and brought instant fame to the young playwright.” W.C. Handy assisted in composing the music, and after Philadelphia, it played Atlantic City for several weeks and then the Apollo.

1916: The show Broadway Rastus evolved into the Broadway Rastus Company, which Broadway Rastus opened the year in Jacksonville, Florida, at the Strand, a complete show, 2 1/2 hours long, with a film as part of its attraction. In April, a new play, Hidden Valley was to open at the Strand, to star Miller, Leigh Whipper, and Chinee Walker.; Quintard Miller was also set to join the show. By September, the company was presenting Mr. Ragtime again, at the Grand Theater in Indianapolis; the Freeman wrote, “Mr. Miller is a stage genius.” In December, their Sultan for a Night at the Washington Theater in Indianapollis starred Bigeou and included the sketch, “Hello, Mr. Green.”

1917: Hell, Mr. Green became a play, opening at the Lincoln Theater, New York, with a “beautiful chorus” in a 30-minute routine.

1918: Irvin C.’s second company played Cincinnati in February while the #1 show played Louisville. By November, his “big musical show” of 15 performers was in continuous performance daily from 2:30 – 11:30 p.m at the New Lincoln Theater.

1919: Esther Bigeou suffered a nervous breakdown.

1920: Miller’s Put and Take played the Town Hall in New York but didn’t do well, but his Alabama Bound became “a sesnastion.” A $10,000 vehicle, it was “the most pretentious production presented to our people, replete with comedy, Jazzy Music, and wonderful scenery.” Publicity also said that it had finished six weeks of “capacity business in New York” before opening at the Dunbar in Chicago in August, where it ran for a week and was followed by another production of Broadway Rastus. The Irvin C. Miller Costume Company was operating in Nashville, Tennessee; the Broadway Rastus Company played Nashville in November before moving to Shreveport at the Hippodrome and then New Year’s for week at the Lyric Theater, New Orleans.

1921: In January, Irvin C. married M. Kate Boyd, the only daughter of Henry Allen Boyd, “noted Baptist leader and publisher.” In July, Miller had Broadway Rastus at the Lafayette in New York and Chocolate Brown at the Howard in Washinfgton, DC. He was also slated to manage the Dunbar Theater in Philadephia for the summer, where would produce “a minstrel and several musical comedies.”

1922: Miller’s Liza, “first of the speed plays,” played at Daley’s Sixty-Third Street Theater in New York. His Hot Dog at the Douglas Theater in July was a “good show, beautifully costumed.” He began rehearsing his Bon Ton Buddy revue for an August opening, but Alex Rogers claimed it was his property; Miller’s Hurry On, with Gertrude Saunders, Lucille Hegamin and a cast of 40, subsequently opened at the Lafayette in New York. To resolve his dispute with Rogers, Miller opened Bon Ton Buddy, Jr. in September, starring Gerriude Saunders and Quintard Miller.

1923: In January, Miller’s How Come oened at the Attucks with a cast of 60 headlined by Salem Tutt Whitney and J. Homer Whitney, Frank Montgomery, and Andrew Tribble; it boasted 12 costume changes. Blanche Thompson, who would become Miller’s third wife, was featured. Charles “Pee Wee” Williams, cornetist and juggler in Miller’s Chocolate Brown show’s olio, received $175 in a judgement against Miller. Miller’s Dinah introduced the Black Bottom to mass audiences.

1924: Late in the year, Miller’s Broadway Rastus Company produced Dancing Days and then Shuffle Along Liza with Quintard Miller at the Bigou Theater in Nashville, Tennessee, to big business.

1925: The Broadway Rastus Company’s chorus of “Liza Girls,” presented as part of a bill at the Attucks Theater, was an early itieration of what would soon become the Brown Skin Models, and it starred two future Models, Lily Yuen and Blanche Thompson.

1926: Lobby display of Miller’s Brown Skin Models was arrested in Cincinnati; charges were dropped, and the display was returned to the show, which was “screaming them everywhere” in week-long engagements at Louisville, St. Louis, and Chicago.

Sources

“The ‘Brown Skin Models’ Like Old Man River, Just Keeps a Rollin'” Chicago Defender [national ed.]18 Feb. 1950: 20

Johnson, James Weldon. Black Manhattan. 1930. New York, Da Capo P, 1991.

Jones, Willie. Personal interview. Philadelphia, PA. August 1987.

Official Theatrical World of Colored Artists: National Directory and Guide. New York. 1928 ed. April 1928: vol. 1, no. 1.

Price, Clay. “Quntard Miller Wins Out.” Chicago Defender. 14 Aug. 1920: 5

Roy, Rob. “Brown Skin Models is back–better some say: Greats of first edition in wings for the opening.” Rob Roy’s Olde Tymer’s scrapbook. Chicago Defender [national ed.] 19. Mar. 1955: 7.

“Routes.” Chicago Defender 14 Aug. 1920: 5.

Sampson, Henry. Blacks in Blackface: A Sourcebook on Early Black Musicals. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow P, 1980.

—. The Ghost Walks: A Chreonological Historyt of Blacks in. Show Business, 1865-1910. Metuchen, NJ, Scarec row P, 1988..

Stearns, Marshall and Jean. Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance. 1968. New York, Da Capo, 1994.

also

Chicago Defender, national edition:

1924 Mar. 29: 4;

Indianapolis Freeman:

1915 Jan. 9: 6

1915 May 22: 5

1918 Feb. 9: 5; 16: 4

1920 Feb. 7: 3; 28: 5

1920 Mar. 20: 6

1920 April 17: 7, 24: 5

1920 May 1: 2; 8: 7; 15: 20; 29: 3

1920 Sept, 4: 6

Billboard, J.A. Jackson’s Page: 1923 May 19: 53

November 23, 2024

Wilson Daily Times