Lord-Warner Pictures, Inc.

Lord-Warner Pictures, Inc.

North Carolina’s Warner Brothers

Although they never rivaled their California namesakes, the Warner brothers from Washington, NC wrote their own regional and little-known history with two films, both made in 1947 by John and Walter Warner. “Pitch a Boogie Woogie,” a 26-minute musical comedy featuret, got limited distribution as one of the last films made exclusively for Black audiences, where it premiered in Greenville in showings for white audiences at the State, and for Blacks at the Plaza. John Warner ran the Plaza, which anchored the dynamic Black retail and nightlife Albemarle Street neighborhood known as the Block, and he was certain that a Cabin in the Sky kind of audience still existed.

The State was also where Lord-Warner Pictures premiered its other film, the 30-minute civic promotional documentary on the city of Greenville, which has been lost.

Credits-readers might not have suspected that Lord & Warner were brothers, raised in a small waterfront community in an apartment in the Washington Hotel, in which their father owned the bar where William, second oldest, sometimes slept. After prohibition began, Dad lost the bar and began drinking heavily; William joined the Navy and John Warner, who didn’t finish high school but was a mechanical genius, married and moved to Greenville, where he hoped to make a living as a sign painter.

William Lord, courtesy of Clyde Gallop

Walter Benjamin Warner (July 17, 1897 – September 26, 1981

Walter Warner died a month after I moved to Greenville, in 1981; his biography is constructed from interviews with family and others who knew him. One nephew said he was “a mystery person” and a “loner,” and that “nobody knew him much at all.” He left North Carolina for New York “with goals to be in the theater” after the war.

Clyde Gallop, who noticed publicity surrounding my research on “Pitch a Boogie Woogie,” led me to a few family contacts, but it was Gallop himself who provided most of these details.

Salutatorian of his class, 1914, despite a perfect 100 average–“political favoritism” made him 2nd best. Accepted to Davidson College but enlisted in Navy and subsequently moved to New York City.

Gallup said that Lord had performed on Broadway, background and chorus parts in three productions, all while in Black-face. Of Porgy & Bess and In Abraham’s Bosom (Paul Green’s 1927 Pulitzer-Prize winner) in blackface. I could find no verification of that claim, but the full cast of The Green Pastures, Marc Connelly’s play noted for Richard Harrison’s portrayal of De Lawd, includes in its chorus the alto John Warner as part of the renowned Hall Johnson choir. Produced in 1930, it is sometimes erroneously called the first all-Black cast Broadway play when, perhaps, it’s the first Broadway production written by a White person with an all-Black cast. It makes sense that William Lord would not want to use his real name, which was at least somewhat known in New York theater circles of the late 1920s and ’30s, and which would disprove the claim of it having an all-Black cast, whether the first or not; and using his brother’s name would be safe. So maybe that’s a detail.

At the City Museum of New York, in the Billy Rose Theater Collection, I found a clipping headlined “Song Writer Sues Club for Barring Negro.” William Lord sought damages for the January 10, 1940 incident at a men’s residence club at 317 W. 56th St. When he attempted to bring Charles H. Dixon, a singer “with 12 years experienc” to his room to rehearse songs, the clerk said “no coloreds” were allowed. Lord said, “This is outrageous and unconstituional.” The clerk replied, “This is our policy and I believe I am entitled to it.”

Gallup said that William Lord knew Mary Martin well, was acquainted with Paul Robeson, and a dear friend of Helen Ware, the vaudeville and silent film actress. Once married, and estranged from his son.

Gallop was the last of William Lord’s lovers, and when we visited, he talked almost non-stop, standing all the while and showing off things not necessarily related to “Pitch”: lots of family genealogies on old scrolls, a settlers’ family tree that shows his family’s intermarriage with Native Americans of Croatan, photos of all his lovers–he recites their names and speculates what’s likely happened to them.

Courtesy of Clyde Gallop

He shows me Bill’s trunk beautifully handmade, pegged, from Honduran mahogany in 1920, while he was stationed in the Virgin Islands, and inside the trunk, Bill’s typewriter, a suitcase, his comb and scissors set, a clock that doesn’t work, swagger sticks hand-carved also from mahogany. We’ve already examined the four framed photos of Bill, three in standing frames on end tables, a fourth, an 8×10 portrait of the Gatsby-looking Bill from the 1920s. The one of him smiling at 75, champagne glass in hand, was the last photo ever made of him.

“He radiated energy and curiosity,” Gallop said. “He was a seeker and had extreme self-confidence though he said it hadn’t always been so, that he was misunderstood when he was young. Although he’s gone, there are times I can feel him close to me, a silent closeness. But he said ‘Don’t grieve, I’m always with you,’ and that’s true.”

They met after Lord had moved back to North Carolina, advertising for a housemate in Raleigh: “I knew as soon as I met him that I’d known him before, that I’d seen him before, because one night I’d seen his face come to me.”

Gallop said that he travels to Arlington National Cemetery every September to place one white rose on Bill’s grave for every year he’s been gone.

Helen Harris met Bill Lord in New York soon after the war, said that he was a stage manager on Green Pastures. She considered Bill “absolutely dynamic,” qualifying with “and I’ve met Cesar Romero.” He was tall and “very handsome–women were crazy about him, but he was gay. He adored me and I adored him. We could look at each other across the room and we’d burst out laughing. Yes, he was so good and so so wonderful–he practically owned Park Avenue. Those women went mad about him.”

By the time the Warners began their company, Walter Warner had long been gone to New York City, where he had become William Lord in the 1920s in a Rosicrucian naming ceremony and pursued a dramatic arts career.

Gallop also said that Lord wrote under the pen name of “William Loder.”

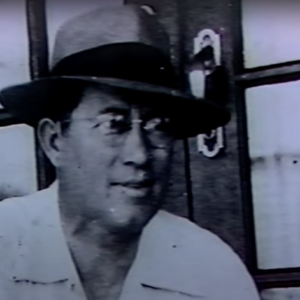

John Warner in doorway of Plaza Theatre, ca 1947. Sam Underwood Papers, Special Collections, ECU.

Sources

Gallup, Clyde. Personal interview. 9 July 1985. Rocky Mount, NC.

Harris, Helen. Telephone interview. July 1985.

Johnson, James Weldon. Black Manhattan. 1930. New York, Da Capo, 1991.

“Song Writer Sues Club for Barring Negro.” New York Herald-Tribune. 14 Feb. 1940.

Underwood, Sam. Personal interview. 19 Feb. 1985. Greenville, NC

–September 17, 2024