Vollis and His Fun Machine

I want to make things that are fun to look at,

that have no propaganda value at all.

—Alexander Calder

Wheels were turning in my head and I had to get them out.

—Vollis Simpson

It’s hard to describe this work or its reason for existence 30 feet above

rural Wilson County.

—Eddie Wooten

1. Wind works art, which dances with it a pirouette on a blue sky canvas or a dark one specked with stars or clouded over. Doesn’t matter. No wind works it, too, with light (and all those reflectors!) and the angles it reflects, infinite. Stand beneath Vollis’s fun machine and whichever way you look upon it, you’ll see framed in the sky a kinetic new vision. On a still day, tilt your head and, still, it changes. Lose the wind you lose the grind and squeak, though still it’s whole as if wind were not required.

But wind’s what makes it fun, Vollis said: Well, it’s got a little whizzy sound to them and you hear a little who-o-o-o … I hang some chimes under them so they’ll make a little music once in a while. It sounds like a piano player, when I had them in mint condition.

2. “Them” is the collection of mammoth whirligigs that Vollis Simpson constructed at his home between the Wilson County communities of Lucama and Rock Ridge, where Willing Worker Road dips down to Wiggins Mill Road and where, once upon a time, pasture and pond, woods and swamp, ditchbank and road, all were filled with flash and groan. After his first one attracted so much attention, Simpson began making more ‘gigs on weekends and as he created a bigger and bigger stir, locally and on the international art scene, he made more more elaborately and then more. The tallest, at sixty feet, has 2,000 reflectors; the heaviest, 13,000 pounds.

Why? Most of the time, my sculptures are about where I’ve been. I love airplanes, so there’s a lot of them, and farm equipment and animals. It’s mainly my history. I’ve done a lot of stuff in my life and I just wanted to do something odd, something people could enjoy and for the children. They bring their little pads and their little notebooks and their little pencils, and I let them sit out there and draw. And I’ll go get them some candy. [When] I know they’re coming I’ll send my wife to Wal-Mart and get a sack full of blow gum candy and pass them all out. [Sometimes the schools] bring a busload down here and stay two or three hours. And sometimes they’ll bring their lunch and I’ll let them have a little picnic out there. It’s fun to see them enjoy themselves.

A beautiful enlargement of this portrait by Burk Uzzle is displayed at the whirligig museum in Wilson.

3. I’m Vollis Simpson. I was born and raised at Old Hog Place place.

Born in 1919, Vollis was one of twelve children. He was a perfect-attendance kind of student at Lucama High School, where he was also president of the Young Tar Heel Farmers, and a 1938 graduate (a 2010 New York Times profile says he “graduated 11th grade,” which, in his Times obituary, got translated to “high school dropout”; public schools in North Carolina then went only through eleven grades) and went to work on his father’s farm, the one his father had farmed. One of their sidelines was house-and-barn moving, and Vollis seems always to have preferred working the moving parts of machines over digging dirt. Drafted in 1941, he served as a staff sergeant in the Army Air Force, stationed on Saipan and working memorably with B-29s, the largest airplanes in the world.

Vollis arrived at Saipan after the awful three-week battle (over 25,000 Japanese soldiers killed), a turning point in the Pacific war because it would mean secure air bases for the new B-29s that would then be within striking distance of Tokyo. But before the B-29s could come to Saipan, they needed a base, with the longest runways ever made. Vollis was among thirty-six North Carolina men commended by Brig. Gen. H.S. Hansell, Jr., commanding general of the 21st Bomber Command, for their expert and expeditious building, between August and October 1944, of Kobler Field on the southern end of Saipan. They “took up the unfamiliar task of airbase construction in addition to their regular duties,” and in addition to their priority task of completing the two 8,500-foot runways was “the unusual assignment of building administrative and service facilities as well as living quarters.”

A Japanese air attack on the base in November 1944 damaged several B-29s, and it may well have been from one of these that Vollis used parts, including propellers, to power a clothes washing machine for his base. Because dozens of Japanese soldiers had disappeared into the jungle instead of surrendering after the battle—the last Japanese on Saipan surrendered months after the war’s conclusion—his base was also under constant threat, so he further honed his mechanical skills by constructing booby traps to protect against night raids. We worked night and day with bombs dropping all around us. I didn’t think I’d ever see Lucama again. I was just lucky, I reckon.

My hand inside a mold of Vollis’s hand, at the whirligig museum in Wilson

Back home, his marriage to Jean Barnes on January 20, 1947, was the first of dozens of Wilson Daily Times news notes from the Lucama and Rock Ridge communities that would detail the Simpsons’ social life regularly through the 1980s: frequent visits with her family, housewarmings, weddings and baby showers, funerals, big Thanksgiving feasts, Vollis and brother Dewey to the 1947 National Air Races in Ohio, excursions to White Lake and Airlie Gardens, Vollis and Jean’s children off to colleges. One front page photo of Jean Barnes Simpson accompanies a story about Governor Terry Sanford’s tax proposals, quoting her: “I think it is hard enough for poor people to manage without taxing essentials. I think we are already taxed enough.” Another shows Vollis comparing his famously large hands to those of girls on a Louisiana softball team (said the novelist Allan Gurganus: “I love shaking his hand. You put your hand on his, and it’s like two catcher’s mitts closing around”). The Simpsons were such respected fixtures in their community that obituaries for both Vollis and Jean’s fathers were front page news.

In 1950, he and two brothers built the machine shop on Willing Worker Road from which he would work as a self-styled jack-of-all-trades until his death in 2013: For 30 years we worked on all kinds of farm and tobacco machinery. We even built our own parts—worked on every kind of machinery: truck bodies, tobacco trucks, you name it. I also had a house-moving business. I learned a lot about balance and adapting machinery in all those years.

His first wind-turbined devices were made for work, not fun—that Army washing machine and a home heating aid he made during the 1970s oil crisis. He moved that one from his home to his pond-side, where it became the basis for his first whirligig and soon began attracting local attention. In 1984, he told a Wilson reporter that he didn’t have a name for the “contraption” he’d built from that heater, or “a reason for its existence.” He called it a mess, and from it grew the collection that within a decade would become “Acid Park.”

He also clearly liked the mess he had made and the attention it garnered, and as he eased into retirement, he filled his days more and more with building contraptions from what others didn’t want. What he collected to use was too good to be thrown away, he said, not “junk,” “industrial waste,” or “abandoned industrial products”: When I built it, I didn’t know anything about art. I still don’t. Didn’t call it nothing. Just go to the junkyard and see what I could get. Went by the iron man, the boat man, the timberman. Ran by every month. If they had no use for it, I took it.

4. Bicycles, tricycles, and cars and their tires, rims and parts, airplane tires, cones, metal headlight rims, scrap iron, reflectors, propellers, go-carts, hubcaps, road signs, HVAC fans of all sizes (Roger Manley noted his preference for “fans from barn [chicken-shed, pig-shed] ventilation systems—in both cases, unlike household fans, they could be super sturdy because you didn’t have to worry about noise or the possibility of chopping fingers off”), ceiling fans, toasters, mirrors, stovepipes, I-beams, pipes, textile mill rollers, ball bearings, aluminum sheeting, various woods, steel rods and bars, rings, pans, milkshake mixers and cups, metal globes, heating oil drums, washing machines, metal wine goblets, roofing tacks, sirens, threaded rods and tie rods, and hundreds of cut-out figures from thick sheet metal, brightly painted stars, ducks, and farm animals were among his particular favorites.

5. I first heard of Vollis from my colleague Jim Barnes at East Carolina University, where I went in 1981 to teach freshman English. “Who knows about Acid Park?” became one of those ice breakers I’d ask at semester’s start, like “Who’s ever ridden in the trunk of a car?” or “Who’s been crapped on by a bird?” Always a few students knew where it was, had been there, knew the story of how this man’s daughter had died in an awful car wreck while tripping on LSD and he’d built this elaborate psychedelic memorial to her: you can even see the car she died in, with reflectors all over the trees around it and the one that’s grown up in it.

After Jim left Greenville, I continued to stop by to visit Vollis, often bringing traveling friends to see what I had subsequently learned was one of two world-class Roadside America–kinds of attractions in eastern North Carolina—the other being Mrs. Way’s Museum, in downtown Belhaven. Vollis was always generous with his time, sometimes working through a visit, and one-on-one always affable, though he’d rail against trespassers, litterers, and vandals who’d ride their four-wheelers through his nearby family cemetery, “overgrown but identifiable, with broken fence enclosure.”

Once I asked him about the Acid Park story, and he leaned into the question with a sudden seriousness: I never had a daughter killed in a wreck. Not until much later would I realize the cruelty of this rural legend. The Simpsons’ third child, their first daughter, had in fact died, not in a wreck but on the day she was born, in 1958, and she was buried in that family cemetery he so vigilantly guarded.

On another visit, he talked about trouble that had arisen when a booby trap attracted the sheriff’s attention. He’d learned booby-trap making in the service, he explained, and the trip-wire worked, but his shotgun’s birdshot load had been aimed too low, and one of the boy’s trucks had been plinked. He agreed to dismantle the booby traps–this may have been related to a February 1992 incident in which a charge of assault resulted in a voluntary dismissal–which were sometimes also set to protect that cemetery. But the trouble didn’t cease.

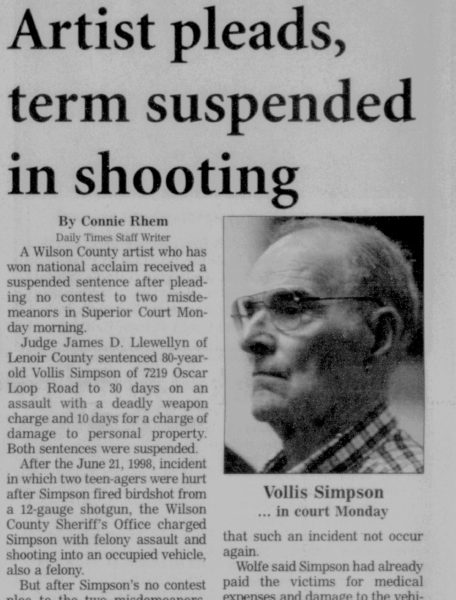

Reports of break-ins and thefts from his shop started in the mid-1960s, but they accelerated after media attention began attracting folks from farther away. It was three teenagers from Garner, an hour west, who triggered his arrest in 1998 on felony charges of assault with a deadly weapon with intent to kill, inflicting serious injury, and discharging a weapon into an occupied property. The indictment came two days after he was featured in People magazine.

The case dragged on for over a year, and the uproar over it brought letters of support to the local paper from artists and museums from all over the U.S. and Europe. Twice the local courtroom was filled beyond safe capacity with local supporters wondering why he’d been so charged when he’d been protecting his property after repeated acts of vandalism: his whirligigs used for target practice, bottles and bricks hurled at them—and him, once leaving his forehead gashed. The vandals, wrote one supporter, “deserve buckshot, not birdshot,” and another argued that those “defacing and desecrating this beautiful spot” deserve the punishment. Had he been “intending to kill, as he is charged, he certainly would have used more powerful ammunition than birdshot.”

In the end, Vollis pled guilty to reduced charges, a couple of misdemeanors, and his thirty-day sentence was suspended. He paid for the emergency room visit two of the teens had made, and for the damages to the other’s truck, and that one’s dad dropped his civil suit against Vollis, who agreed not to have guns on his property for five years and to submit to warrantless searches for weapons.

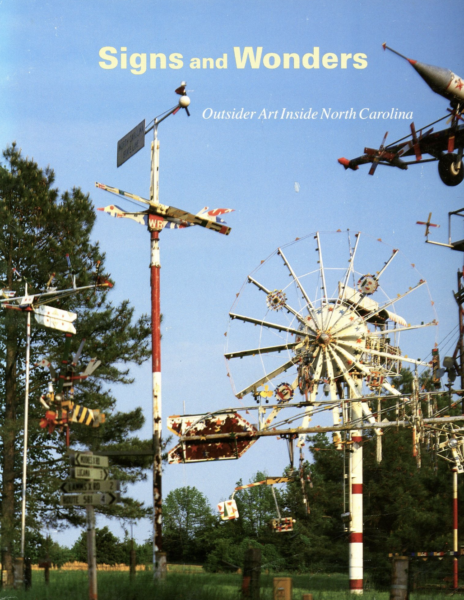

6. Only a few eastern North Carolina natives have their work included in the North Carolina Museum of Art’s permanent collection. Wilmington’s Claude Howell got accepted into his first juried show when Vollis was a high school junior and future farmer. Kinston’s Henry Pearson drew maps for the Okinawa campaign, a couple thousand miles away from Vollis, in World War II; they’d both have gone to Hawaii for R&R. And Long Creek’s Minnie Evans—how I love to imagine her working the gate at Airlie Gardens that day when the Simpsons came to visit, soon after the gardens opened in 1949, Vollis pausing to study her paintings. The Museum’s spectacular 1989 show Signs and Wonders: Outsider Art Inside North Carolina brought his art to the attention of a worldwide audience, and the wrap-around photo by Roger Manley on the oversized catalog for that show is still the best static depiction of the site where it all began. These days, Wind Machine, which Vollis constructed especially for the Museum in 2002, looks a little lost in the landscape at the top of a lovely sculpture trail far removed from the five-points in rural Wilson County that used to be dominated by the most fanciful of personal parks.

6. Only a few eastern North Carolina natives have their work included in the North Carolina Museum of Art’s permanent collection. Wilmington’s Claude Howell got accepted into his first juried show when Vollis was a high school junior and future farmer. Kinston’s Henry Pearson drew maps for the Okinawa campaign, a couple thousand miles away from Vollis, in World War II; they’d both have gone to Hawaii for R&R. And Long Creek’s Minnie Evans—how I love to imagine her working the gate at Airlie Gardens that day when the Simpsons came to visit, soon after the gardens opened in 1949, Vollis pausing to study her paintings. The Museum’s spectacular 1989 show Signs and Wonders: Outsider Art Inside North Carolina brought his art to the attention of a worldwide audience, and the wrap-around photo by Roger Manley on the oversized catalog for that show is still the best static depiction of the site where it all began. These days, Wind Machine, which Vollis constructed especially for the Museum in 2002, looks a little lost in the landscape at the top of a lovely sculpture trail far removed from the five-points in rural Wilson County that used to be dominated by the most fanciful of personal parks.

The last Vollis whirligig standing at Willing Worker Road, 2019. RAFoto.

Most of Vollis’s fun machines have made the ten-mile move to Wilson, where they populate the Vollis Simpson Whirligig Park, and the site where they used to stand is ghostly quiet, like it had become as Simpson became unable to maintain their moving parts, and the mechanical symphony that permeated his environment was choked out by rust and vines that have now reclaimed almost all of what used to be his shop. One lone giant, safe inside an electric company chain link fence, still moves creakingly; the grass beneath it has been weed-eaten around its parts most recently shed. But still it works.

7. Heft and balance, air and color,

shadow and shape, form within form,

motion, mass (and massive).

Geared: how one thing working works another

and it, another,

so long as the grease holds.

Pause draws an arabesque.

What you see depends on time and place:

how long you’ve got

and when and where you stand

to watch a constellation drawn

with cutout stars and landfill gleans.

• • •

Vollis Simpson, Wind Machine, 2002, steel and other media, H. 30 x W. 30 x D. 15 ft., Commissioned by the North Carolina Museum of Art with funds from the William R. Roberson Jr. and Frances M. Roberson Endowed Fund for North Carolina Art. RAFoto 2019.

Vollis Simpson, Wind Machine, 2002, steel and other media, H. 30 x W. 30 x D. 15 ft., Commissioned by the North Carolina Museum of Art with funds from the William R. Roberson Jr. and Frances M. Roberson Endowed Fund for North Carolina Art. RAFoto 2019.

Sources used in writing “Vollis and His Fun Machine”

Batts, Lisa Boykin. “Folk Artist Vollis Simpson Dies at 94.” Wilson Daily Times. 1 June 2013: 1, 3.

—. ”The Man behind the Whirligigs,” in Vollis Simpson Whirligig Park.

Ball, Sandra, Sudie C. Forbes and Mark Hathaway. ”Hawley/Howell Cemetery.” 8 May 1993. Survey of Graves in Wilson County. [Wilson, NC] n.d.: 149.

“Barnes-Simpson Marriage Announced.” Wilson Daily Times 23 Jan.1947: 5.

Calder, Alexander. qtd. in Rodman.

Currie, Jefferson and Vollis Simpson: “Portfolio: Vollis Simpson Whirligigs.” southwritlarge. n.d. Web. 17 Aug. 2020.

Edgers, Geoff. “A Field Full of Windmills.” Raleigh News & Observer 2 Aug. 1998: 2D, 5D.

“Infant Simpson.” Wilson Daily Times 7 June 1958: 2.

Joel, Jane M. “Vollis Simpson: the Don Quixote of East-Central North Carolina.” Folk Art Society of America. folkart.org. n.d. [1996] Web. 14 Aug. 2020.

Kampe, Adam. “Vollis Simpson: Making Something out of Nothing.” NEA Arts Magazine. arts. gov. n.d. Web. 3 July 2020.

Kosterman, Carol. “Simpson is a Jack of All Trades.” Wilson Daily Times 14 July 1986: 10.

“L.C. Barnes Dies; Funeral Services Set.” Wilson Daily Times 22 Apr. 1971: 1.

“Lucama Man Dies of Heart Attack.” Wilson Daily Times 17 Mar. 1953: 1.

Manley, Roger. Email to author. 25 June 2020.

—.. Signs and Wonders: Outsider Art Inside North Carolina. Raleigh. NC Museum of Art, 1989.

Montgomery, Jackie. “Getting to Know Us.” Wilson Daily Times 18 Aug. 2000: C1.

Oppenheimer, Ann F. “She Supports Simpson.” Wilson Daily Times 11 July 1998: 10.

“Personals.” Wilson Daily Times 29 Aug. 1947: 5.

Rhem, Connie. “Artist Pleads, Term Suspended in Shooting.” Wilson Daily Times 29 June 1999: 1.

Rhem, Connie. “Artist Pleads, Term Suspended in Shooting.” Wilson Daily Times 29 June 1999: 1.

—. “Crowding Stalls Court.” Wilson Daily Times 29 June 1999: 1, 2.

—. “Vollis Simpson Case Put on Hold.” Wilson Daily Times 28 July 1998: 2.

“Rights to Protect Property at Issue.” Wilson Daily Times 27 June 1998: 16.

Rodman, Selden, ed. Conversations with Alexander Calder, New York: Devin-Adair, 1957: 136.

Shane, Scott. “Junkyard Poet of Whirligigs and Windmills.” New York Times 6 Apr. 2010: C1.

“Simpson Family.” History of Wilson County and Its Families. Wilson County’s 130th Anniversary Committee. Dallas, TX. Taylor Pub., 1985.

Simpson, Thea, “Local Welder’s Whirlygigs Gain Fame as ‘Outsider’ Art.” Wilson Daily Times 9 Oct. 1997: 57

—. “Lucama Man’s Windmills Turn Heads in Museums across Country.” Wilson Daily Times 23 Apr. 1998: 4C.

Smith, Michael. “Governor Sanford’s Tax Proposals Draw Strong Criticism in Wilson.” Wilson Daily Times 3 Mar. 1961: 1.

“S. Sgt. Vallis [sic] Simpson.” Wilson County Veterans. [Wilson, NC], n.d.: 272.

Stair, Margaret J. “Artist’s Supporters Back Property Rights.” Wilson Daily Times 26 Sept. 1998: 1.

Tarleton, Hal. “Windmill Builder Featured in Time.” Wilson Daily Times 9 Aug. 1989: 1, 3.

“36 Tar Heels Help Build Saipan Base, Sgt. Vollis Simpson Commended.” Wilson Daily Times 3 Feb. 1945: 1.

Vitiello, Chris. “The Extraordinary Legacy of Vollis Simpson.” indyweek.com. 5 June 2013. Web. 17 Aug. 2020.

Vollis Simpson Whirligig Park: A Guide for Explorers. Wilson Daily Times n.d. [2017]

Waggoner, Martha. “Vollis Simpson.” Associated Press. tenneseean.com. 1 June 2013. Web. 14 Aug. 2020.

Wilkerson, Heather. “People Features Folk Artist.” Wilson Daily Times 16 Dec. 1998: 1.

Wooten, Eddie. “Simpson’s Work Blows in the Wind.” Wilson Daily Times 10 Dec. 1984: 3.

Yardley, William. “Vollis Simpson, Visionary Artist of the Junkyard, Dies at 94.” nytimes.com. 5 June 2013. Web. 14 Aug. 2020.

Also a survey of news and social notes from the Wilson Daily Times, 1919 – 2020.

• • •

“Vollis and His Fun Machine” was originally published in the 2021 NC Museum of Art book You Are the River: Literature inspired by the North Carolina Museum of Art. For the book, Helena Feder asked North Carolina writers to respond to an item of their choice from the museum’s collection, and I was delighted that mine, to write about Vollis’s “Wind Machine,” became part of the project. It spins 24/7 on the lawn at the museum in Raleigh.

It’s a beautifully produced large format book, more than reasonably priced ($25 via the museum).

The essay was great fun to put together, mostly from a lot of other sources, especially those who had interviewed him. It’s basically constructed as a kind of Vollis bio made from those interviews, news, and local history details I discovered primarily at the Wilson County Public Library.

Unfortunately, the museum cut my sources during production, making it appear as though I had somehow conducted all the interviews that resulted in Vollis’ extended comments throughout the essay. Although I visited with him many times over the years, it seemed by the time I met him in the late 1980s there was already enough being written about him, and that, perhaps, he had had enough of that kind of attention and the kinds of folks it brought to his piece of Wilson County.

Anyway, I couldn’t have written very much of this essay without all those sources, now included with the essay, especially from back issues of the Wilson Daily Times, and I’m sorry these credits weren’t included in the book.

The shop on Willing Worker Road, 2019. RAFoto.

Vollis Simpson Whirligig Park. RAFoto 2020.