photo courtesy of Michael Bayes, US Navy archivist, and the U.S. Navy

During World War II, over 6,800 musicians served in the U.S. Navy in about 285 bands. Over 100 of these bands were comprised of African Americans. All but B-1 were trained at Camp Robert Smalls, one of three camps outside of Chicago that were collectively known as Great Lakes. Camp Smalls was the primary training post for African Americans, who began arriving in large numbers in August 1942 to train for jobs in the many ratings that had opened up to Blacks as the Navy eased its segregationist policies. Although not officially a Navy School of Music, barracks 1812 at Camp Smalls functioned as one. Directed by Leonard L. Bowden, a well-known teacher and bandleader who appears also to have been in charge of much of the recruiting for the Navy’s Black bands, it provided an intense learning experience for the musicians who lived there. Most Navy bandsmen were already accomplished musicians, a necessity because the Navy’s School of Music was for whites only. Bowden also recruited musicians from other ratings after they arrived at Great Lakes for training.

One of several thousand unknown African-American musicians who served in the Navy during World War II, photographed by Charles “Teenie” Harris at his Pittsburgh studio. Harris was the primary photographer for the Pittsburgh Courier. Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art.

Samuel Floyd has called the Great Lakes experience “the greatest single educational and musical experience for Blacks ever to occur in America.” His monograph, The Great Lakes Experience, 1942-45, is the primary document on these bands. Many of those who came through Great Lakes had already had some formal music training and some were professional musicians; others were recruited from African-American sailors sent to Camp Smalls at other ratings. Concert and marching bands from Black colleges “contributed to the high musical proficiency” of the Navy musicians, writes Floyd, who numbers them at more than 5,000. The Chicago Defender reports that H. Noble Simms trained more than 100 bands at Great Lakes. Simms was one of Bowden’s three assistants; the others: Russell Boone, who was charged with training drum majors in band directing and the bands in military ceremony; and Jimmy Canada, who was in charge of arrangers.

The Navy recognized the value of recruiting musicians for two reasons. First, as a way to help placate Black leaders who for the most part wanted integrated units, the musician rank was deemed an appropriate one at which to make public the Navy’s new policy that took effect on June 1, 1942 to allow Blacks to enlist at ranks higher than messman. Individual units remained segregated. Second, for the sailors themselves, at duty stations throughout the U.S. and in the Pacific, the enlisting of many of the nation’s top jazzmen meant an elevated level of entertainment that would ultimately lessen the stresses of service.

Alton Augustus Adams stands apart from this history. One historian described his role in leading a Navy band of African-American musicians during World War I as “an exceptional situation inspired by exceptional circumstances.” The same held true in World War II. Adams became a Navy band leader and chief petty officer when the U.S. bought the Virgin Islands from Denmark in 1917; Adams was the leader of a popular band that was inducted whole into the Navy to help ease racial tensions. He left the service in 1933 but was called back in early July 1942 to lead a White band stationed at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. He brought along with him “a number of his former members” of Black bands, using “colored musicians along with the White players and the earth continued to revolve on its axis without a jolt.” By war’s end, he was once again leading an all-Black band, this one in Puerto Rico.

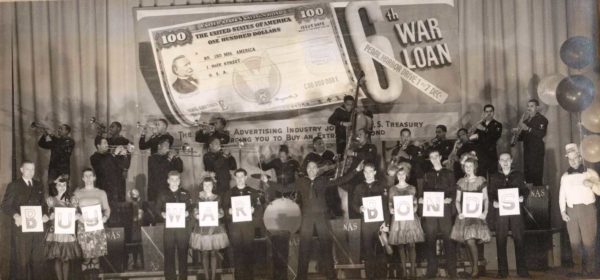

Black audience newspapers of the time carried frequent notices about the losses from the best jazz bands, White and Black, to both the Army and Navy. The Navy’s bandsmen had to be be better than jazzmen, though, as most would be required wherever they wound up being stationed to perform symphonic works, patriotic pieces, martial music and Americana, as well as popular songs and jazz. They would also have to know how to march, as parading for bond rallies would be a frequent assignment. The Navy’s job, at Camp Smalls, was to instruct them in all of this.

Von Freeman, the Chicago jazzman who also played with the Navy’s Hellcats in Hawaii, recalled: “All of the great musicians ended up at Great Lakes. It was an incubator for the best and the brightest lights in the jazz world at that time, and the musical jam sessions were simply phenomenal.” In addition to the main regimental band at Camp Robert Smalls, bands were also formed for Camps Lawrence and Moffett, part of the Great Lakes complex. Bowden directed the Camp Smalls band and from the three bands, he selected and led an all-star band that performed special concerts and played on a weekly “Men o’ War Radio Show,” which was broadcast from WBBM in Chicago every Saturday night, the “only all-Black service show presented weekly over a radio network.”

Also featured on the radio show were a 200-voice regimental choir, a vocal octet, and a vocal quartet, Flats and Sharps.

In addition to Floyd’s seminal work in documenting Black Navy bands, Clark Terry’s autobiography is an excellent source of first-hand information about the experiences of Black musicians in the Navy. Terry had known Bowden from the pre-war music scene in St. Louis. Bowden, who joined the Navy on August 20, 1942, had been band director at Tuskegee Institute, his alma mater. In 1922, he was band director at the Alabama Reform School at Mt. Meigs, and then band director at Alabama A&M, where he helped establish the Bama State Collegians. He was leading his own band in St. Louis before enlisting. His job was to direct the music programs that would be developed at Camp Robert Smalls. According to Terry, Bowden was in charge of new musician recruits but how much he traveled to recruit is not clear.

Bowden’s experience in St. Louis enabled him to successfully recruit other talented musicians from there, including several from the Jeter-Pilars Orchestra: James Cannady, guitarist and arranger; Roy Torian, a trombonist who had been treasurer of the Musicians Equity Association, the “race sub-local of the American Federation of Musicians”; Merrill Tarrant, trumpet; Charles Pilars, saxophone; and Elbert Clabrook, trumpet. They all went to Camp Smalls for basic training, where, by May 1943, “scores of musicians from leading bands and orchestras” had reported for duty at musicians ratings.

Recruiting for Navy bands was done through extensive publicity in Black audience newspapers and also by direct recruiting wherever there were Black local musicians unions, Seattle, San Francisco, New Orleans, St. Louis, and Chicago especially. And in addition to the many outstanding college players, a surprising number of high school musicians were recruited–at least nine from Dudley High School in Greensboro, NC, which had a 100-piece marching band directed by James B. Parsons, and several others from Industrial High School in Birmingham, where Fess Whatley was their instructor. When NC A&T’s band director, Bernard Mason, was unable to pass his physical to enlist and serve as Navy B-1’s director, Parsons was recruited for that position.

With the exception of those bands led by World War I vet Alton Augustus Adams, all of the Navy’s Black bands in World War II but B-1 were headed by White bandmasters. The Navy twice tried to replace Parsons with White bandmasters but on both occasions–once in Chapel Hill and again at Pearl Harbor–bandsmen would squeak their clarinets or saxophones during a National Anthem rehearsal until the designated White replacement gave the baton back to Parsons, who was never awarded the rank of bandmaster; he retired at musician first class.

John Coltrane and Lou Donaldson were two of the best of those who were recruited as musicians after joining the Navy. Coltrane was originally an apprentice seaman, the rating he held when he was shipped to Manana Barracks at Pearl Harbor, but his musical talent got him transferred from a construction detail to a job with the base band, the Melody Masters, which he eventually led.

Donaldson told Marc Myers in a 2010 interview that he was in radar school at Great Lakes and doing quite well at it when he wandered by the base’s band room and heard a clarinet squeak: “I stuck my head in to see who was making that noise. The bandmaster was giving a guy a lesson. The guy was playing ‘Barnum and Bailey’s Favorite,’ a march.” After being noticed listening by the bandmaster, who asked if he could play, the bandmaster “put music up on the stand and asked me to read it. I did. He put up another song. I read that down, too. He said, ‘You are the best clarinet player I’ve heard around here. Do you want to join the band? Do you play the saxophone too?'” And though he’d never touched one, Donaldson said yes and was issued an alto sax and clarinet and given a musicians rating.

Donaldson had been a student at NC A&T when he enlisted. Like Von Freeman, he started out in the base’s C band, made up of most of the younger guys. But everyone mixed when it came to jamming. “The musicians in the different bands used to get together and hold jam sessions,” Donaldson told Myers. “I’d sit in and learn stuff. That’s where I met Clark Terry.”

The Camp Smalls band, or A band, was featured in the “Forty Million in Forty Days” campaign in Chicago in 1943, using a “stump the band” approach: for a liberal donation, they would perform any three compositions requested by the donor, and they were never stumped. The Company A band also performed a spectacular open-air concert at Comisky Park that was broadcast on July 8, 1944.

Floyd writes that bandsmen trained at Great Lakes were shipped out to various bases across the country in 25-piece units and that one 45-piece (or regimental) band was sent to Chapel Hill. But he, like others, conflates two bands that served in Chapel Hill. B-1, the first to be stationed there, was a regimental band; it trained at Norfolk in June and July 1942 because the Great Lakes facilities were not complete. B-1 was replaced in Chapel Hill by a 25-piece Great Lakes-trained band in May 1944. The one regimental band (but with 32 pieces) that left Great Lakes was sent to St. Mary’s College in Moraga, California, to be stationed with the pre-flight school there. The Navy also kept at least one White regimental band stationed at its Music School.

Floyd writes that bandsmen trained at Great Lakes were shipped out to various bases across the country in 25-piece units and that one 45-piece (or regimental) band was sent to Chapel Hill. But he, like others, conflates two bands that served in Chapel Hill. B-1, the first to be stationed there, was a regimental band; it trained at Norfolk in June and July 1942 because the Great Lakes facilities were not complete. B-1 was replaced in Chapel Hill by a 25-piece Great Lakes-trained band in May 1944. The one regimental band (but with 32 pieces) that left Great Lakes was sent to St. Mary’s College in Moraga, California, to be stationed with the pre-flight school there. The Navy also kept at least one White regimental band stationed at its Music School.

Most Black bands were billeted on the base they served, and their duties were exclusively music related. They played for military functions at command and for public occasions such as bond rallies and parades and ships launchings, and also for varieties of public events at almost any kind of venue. Smaller bands cut from the main band at each base also played at dances for officers, at base functions and at USOs, and it is not unusual to find evidence of Navy bandsmen moonlighting with other professional combos at night, especially in San Francisco, Seattle, and New Orleans, in their rich jazz scenes. Although bandsmen were supposed to be assigned tasks only related to their musicians rating, documented conflicts over menial assignments given to bandsmen occurred in St. Louis and Hawaii and no doubt elsewhere.

For the most part, the civilian worlds that surrounded the bases on which the bands worked were rigidly segregated. Dance bands were accustomed to playing in places that they would not have been allowed to enter were they not with the band, an extension of the civilian world in a place like New Orleans, where most of the Bourbon Street clubs were closed to Black patrons. When the Navy bands from the Lakefront and Algiers stations performed in a big bond rally parade in 1943, the Chicago Defender headlined its coverage “Lily White Parade for New Orleans’ Navy Day” and noted that the parade was “without a single Negro face except those furnishing the music by which their White ‘comrades’ marched.”

The accompanying list of Navy bands is woefully incomplete, a work in progress. Some base bands took on non-Navy names; when possible, all are listed according to the Navy base where they were stationed. Bases did not necessarily keep the same bands for the duration of the war, the Navy generally didn’t keep records of unit bands, and bands did not necessarily stay together, although several were recruited as whole or nearly whole bands and for the most part stayed together for the duration of their service.

For an entertaining program that also provides historical background on the service of African Americans in U.S. Navy bands, watch Navy Pioneers: A History of African Americans in the Navy Music Program, a Smithsonian Institute production that was written by Navy band archivist Senior Chief Musician Michael Bayes.

—Alex Albright

February 6, 2025

Sources

Albright, Alex. The Forgotten First: B-1 and the Integration of the Modern Navy. Fountain, NC: R.A. Fountain, 2013.

Clague, Mark. The Memoirs of Alton Augustus Adams, Sr.: First Black Bandmaster of the United States Navy. Berkeley, U of California P. 2008.

Floyd, Samuel A. The Great Lakes Experience, 1942-45. Carbondale, IL: S. Illinois U, 1974.

—. “An Oral History: The Great Lakes Experience.” The Black Experience in Music 11.1 (Spring 1983): 41-61.

“Jeter-Pillars Orchestra Loses Men to the Army and Navy.” Chicago Defender 3 Oct. 1942: 21.

“Lily White Parade for New Orleans’ Navy Day.” Chicago Defender 6 Nov. 1943: 12.

“A Little Known Legacy: The Great Lakes Experience: A Salute to African American Navy Bandsmen at the Great Lakes Naval Base, 1942-1945. A Weekend of Nostalgia, Feb. 28 – Mar. 2, 2003.” Chicago, IL: Feb. 2003.

Myers, Marc. “Lou Donaldson Interviews.” Jazz Wax. June 2010. 3-parts. Web. 29 July 2014.

“Navy Musician Trains over 100 Bands.” Chicago Defender 25 Aug. 1945: 14.

“Navy’s Three Sees Troupe as One of the Greatest.” Chicago Defender 9 Oct. 1943: 19.

Porter, Lewis. John Coltrane: His Life and Music. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1999.

“Gaillard in Texas” [?] Baltimore, MD. Afro American: 6 Apr. 1944: 6.

Strawther, Larry. Emails to author. 5, 6 June 2016.

Terry, Clark, Gwen Terry and Bill Cosby. Clark: The Autobiography of Clark Terry. Berkeley, CA: U of California P, 2011.

“U.S. Navy Bandmaster Leads White Navy Players in Cuba.” Chicago Defender 25 July 1942: 9.

“Willie Smith of Lunceford Crew Is among others Starred Here.” Chicago Defender 15 May 1943: 19.

• • •

James A. Albright’s official Navy portrait was taken in New London, CT.

My father’s first Navy duty station, in 1942, was at New London, Connecticut. As a family en route from NC to Cape Cod in 1964, we drove there for a look; none of us but him were interested in anything about this detour. I can only imagine that he might have at least wanted to get out of our new Plymouth Fury, and that he might also have shared a memory or two.

After New London, he was transferred to one of the Great Lakes bases. One night, he helped a drunken officer get back to base; that officer had enough clout to pull Dad’s orders for the Pacific, so his duration wound up being in Chicago, where he worked as an airplane mechanic for the duration of the war. He loved music–one of his favorites to sing was Slim Gaillard’s “Flat Foot Floogie with the Floy Floy.” During the war, Army Corporal Gaillard was an airplane mechanic at Laughlin Field, Del Rio, Texas.