Algiers Station Navy Band. Courtesy of Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

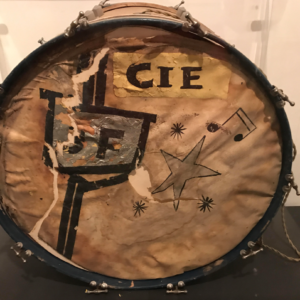

Cie Frazier’s drum. RAFoto, New Orleans Jazz Museum

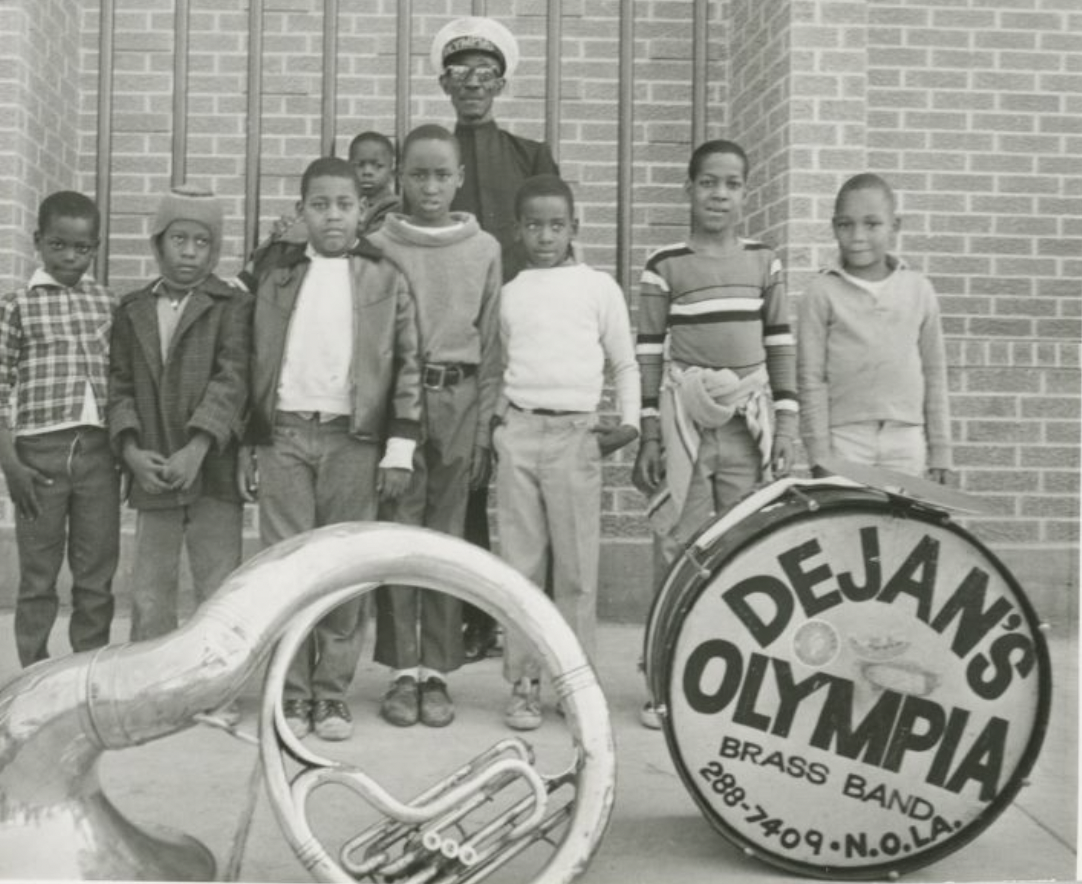

Harold Dejan thought that the Navy band at Lakefront had gotten “the cream of the crop” of local musicians. “They took all the best musicians you could find,” he recalled, including his brother, Leo, and Willie Humphrey. “They had all the top musicians.” Wendell Eugene, who played in that band, agreed, telling Barry Martyn in 1999 that the Lakefront band was clearly the better of the two. But the Algiers band also had an impressive roster of some of New Orleans’ finest musicians, including several locals from the Bourbon Street Black community: Harold Dejan, Tats Alexander, Polo Barnes, Cie Frazier, and William Casimir. George Williams and Reuben Roddy are perfect embodiments of musicians who became part of that community by their immersion into it: both were born elsewhere but stayed in New Orleans after the war as prominent players in dance bands and brass band parades.

From their ranks came a Dixieland band and, with other locals–Booker T. Glass, for example–one of the most popular dance bands in town, the Gobs of Rhythm which, by late in the war, was doing Gypsy Tea Room battles (where “the cats and chicks are all on the beam and stay that way”) with other hot bands. Like the other Navy bands, they trained at Great Lakes–Harold Dejan recalls 16 weeks there–but the timing of their arrival at Algiers and commencement of musicians duties remains unclear. Given that several of the members played with Papa Celestin, it’s possible that he was still leading the WPA #4 band that was still active in New Orleans’ Black communities in late 1942, and that these enlistments might have coincided with the WPA band’s dissolution.

From their ranks came a Dixieland band and, with other locals–Booker T. Glass, for example–one of the most popular dance bands in town, the Gobs of Rhythm which, by late in the war, was doing Gypsy Tea Room battles (where “the cats and chicks are all on the beam and stay that way”) with other hot bands. Like the other Navy bands, they trained at Great Lakes–Harold Dejan recalls 16 weeks there–but the timing of their arrival at Algiers and commencement of musicians duties remains unclear. Given that several of the members played with Papa Celestin, it’s possible that he was still leading the WPA #4 band that was still active in New Orleans’ Black communities in late 1942, and that these enlistments might have coincided with the WPA band’s dissolution.

Top row: Bandmaster Vernon B. Cooper, Booker Washington, Alexander William Spencer, Paul Barnes, Herbert Trist/Trisch, William Casimir, Sidney Dufachard, Leon Harris, Frank Fields. Bottom row: Gilbert Jones, Vernon Gilbert, Robert Anthony, Bertrand Adams, Thomas Brooks, unknown, John Jones, Henry Ross Davis, Harold Dejan, Adolphe Alexander, Jr. Courtesy of the New Orleans Jazz Club Collection of the Louisiana State Museum.

That Algiers station would get a black Navy band was announced locally in the Louisiana Weekly on August 15, 1942: “Heartening news to local Negroes who were unable to enlist as members of the first band is the announcement made today by Lieutenant Kenneth C. Elliot, officer in charge of the local recruiting station, that another navy band would be formed within the next few days.” It would have the same qualifications: “Applicants must not be under 17 years of age and not over 50. They must be able to pass the navy physical examination, and must be able to read music scores. There are no educational requirements.”

Harold Dejan’s recollection of how long the band stayed at Great Lakes would put their arrival in Algiers at no earlier than January 1943. “Every time we were supposed to leave, ” he said, “they made our chief recruit another band. So we took off from boots about three times. Everything went well. Oh, you wouldn’t know there were so many musicians in the world.”

Dejan said that the band played parades quite often: “We used to start playing a march at the river and Canal and play a medley of marches and end up at Rampart and Canal, that’s right. We had a good band.” At Algiers, Dejan played tenor sax with the marching band, baritone sax and clarinet with the orchestra, and in a Dixieland band he led he played alto sax. Dejan also played in what he called a “mixed band” while stationed at Algiers—it included white musicians.

1942 saxophone section, Algiers Naval Station band, bottom up: Harold Dejan, Adolphe Alexander, Jr., H. Trisch, Paul Barnes, William Casimir, with Bandmaster Vernon B. Cooper. Courtesy of New Orleans Jazz Club Collection of the Louisiana State Museum.

The Louisiana Weekly‘s “Here It Is” column, written by a local identified only as Mike, reported in August 1944 that the Gobs of Rhythm “can dish it up a la [Sidney] Desvigne any old time and then some.” Mike announced in April 1945 that Desvigne’s band would battle the Gobs of Rhythm at the Gypsy Tea Room, also calling the Gobs a “mixed band.” He notes that the band is led by Bertrand Adams. Other players listed include Pete De Mio (also known as “Grayboy”) and a “bass digger [who] is also of the same race,” and three Navy bandsmen: Polo Barnes, Bill Casimir, and Dejan.

Mike doesn’t report who won this battle, but he writes in early 1945, “The Gobs of Rhythm are about tops in these circles.”

The Algiers Naval Station was commissioned in 1901 as a dry dock that was operational by January 1902. It proved “perfect in all details” and helped the port of New Orleans because it was usable by merchant vessels and warships alike. Congress appropriated almost $5 million additional for the construction of new buildings and other improvements and the purchase of additional land which pushed the station’s river frontage to 3,700 feet with a depth of 3,000 feet. The station was closed briefly for financial reasons about 1913 but reopened in 1915 after Secretary of Navy Josephus Daniels and his assistant, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, visited the site and “were impressed by the splendor of its buildings and their outstanding care and maintenance.” Principal among these buildings was a plantation house on the grounds that had attracted the attention of President Theodore Roosevelt and his daughter, Alice, during inspections for the dry dock. The President ordered that the stately magnolias on the base site not be disturbed and recommended that the mansion be used as the Admiral’s home. It later became the home of the Commandant of the Eighth Naval District. During World War II, Algiers Station operated as Receiving Station and Industrial Navy Yard for repairing vessels, housing machine, blacksmith, boiler, and carpentry shops and a foundry with “the largest rollers for rolling steel plates in the South.” Submarine chasers, 88-foot harbor tugs, and seaplane wrecking barges were built there, and captured German ships were repaired and remodeled. The base also included a supply department and hospital, and a fireman’s and machinist mate’s school. Most operations at the base ceased in June 1933, and for the next two years the base was used to house transient military personnel; from December 1938 to September 1942, the National Youth Administration used most of the station as a training school, housing as many as 1,500 youth at a time. The original dry dock was disassembled and sent through the Panama Canal to Pearl Harbor in the buildup to World War II, which saw a resurgent Navy presence at Algiers; the naval station was formally re-opened in 1939. During World War II, the base had a supply department used to outfit the many Navy vessels being constructed in the region; an armed guard center that trained guards for merchant ships; an inspections center; a landing craft program that outfitted LST (landing supply troop) vessels; and a new dry dock. Also operational there were firefighting and gunnery schools.

Except for the band, who were all musician-rated, and steward-rated sailors, all who served at Algiers Naval Station were White.

Although not much is currently known about the activities of the Algiers Station Navy Band, a roster of musicians who played with it is impressive:

The Gobs of Rhythm with unknown vocalist. Smithsonian Institute of Museum of African-American History.

Bertrand and Hazel Adams. Houston-Tilotson University.

Bertrand Adams, trombone.

Born April 29, 1912, died January 4, 1999.

Adams, from Waco, Texas, was the band director at Wiley College, where had graduated, prior to enlisting in the Navy band. He married his college sweetheart, Hazel Madree Poole, in 1941.

After the war, he and his wife moved to Austin, Texas, where they joined the faculty of Samuel Huston College, he in music, she in health; they both taught for the next decade. Samuel Huston College, now Huston-Tillotson University, was “once an East Austin institution that was a primary destination for promising musicians from around the country — drawn by a nationally renowned music program and names like Nat Williams and Bert Adams who offered education, cultural enrichment, and opportunity.”

Adams was named an Austin Living Legend in 1990 and inducted into the Clarksville West End Jazz and Arts Hall of Fame in 1994. His 18-piece band played alongside Nat King Cole in concert in 1947.

Cie Frazier recalls that Adams was one of two principal arrangers for the Algiers band, and Adams is cited by Mike in his “Here It Is” column as leader of the Gobs of Rhythm.

Tats Alexander (2nd from R) with Bunk Johnson (L) in 1945. Photo courtesy of Historic New Orleans Collection

Adolphe Leonce Alexander, Jr. saxophones, clarinet, bass horn. July 15, 1898-1968.

Tats, the oldest of the Navy bandsmen at Algiers, was born into a musical family at St. Philip and Deberginy Streets. His father, known as Taton because he was short, taught music but hadn’t the patience to teach his own children, so Tats, his brother, and three sisters learned from a succession of neighbors, for Tats most notably “Papa” Tio, Sr., until he gave up teaching because of illness, and Tats then finished studies under Alphonse Picou.

As well as “Tats,” he was also known to fellow musicians as “Biscuit,” in part because he worked at a the Pelican Cracker Factory and had a fondness for eating crackers.

He was with the Tuxedo Brass Band in 1921, then played on riverboats with Sidney Desvigne’s orchestra while also working with Manuel Perez on the Rooftop Garden for a couple of years, and then with Clarence Desdune’s orchestra.

During the Depression, when “t’ings was getting bad, getting critical ’round here,” he got work with the WPA band before joining the Navy, where he began playing baritone horn. “Didn’t need lessons,” he said. “The fingering’s the same, just had to hear it.” With the WPA band, he said, “I’d take the orchestration home and I’d write a solo part for the baritone. In the Navy we had all the music already printed.” He had begun studies on baritone with the Albert system of fingering but changed to Boehm because, he said, those were the only books that the Navy would buy.

After the war, he was in New York and also with with Bunk Johnson’s band back in New Orleans in 1945. He played with Papa Celestin’s band into the mid-1950s and except for occasional gigs, especially around Carnival time, he retired from music in 1955.

Robert Anthony, trumpet.

Polo Barnes photographed by Ralston Crawford, 1958, at the Autocrat Club. Courtesy of Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University

Paul D. “Polo” Barnes, clarinet, sax.

b. NOLA Nov 22, 1902; d. NOLA April 13, 1981.

The brother of Emile Barnes, Polo started playing on a ten cent fife. He and Cie Frazier paraded as children with fife and snare drum and would entertain local students. He had a big musical family on both sides: his mother’s sisters were Marreros–his aunt’s kids all string players, his mother’s all instrumentalists. He took a few lessons from Lorenzo Tio, Jr. but considered himself mostly self-taught. In his first band, formed in 1919 with Frazier (who remembered it was called the Golden Rule Band and said it was the basis for the Original Tuxedo Band) and the Marrero brothers, Eddie and Lawrence, he played alto, what he believed was the only one in New Orleans at the time: “They were all playing clarinets, and my playing that alto saxophone was so successful that it changed the whole city of New Orleans to saxophone.”

He played with the Young Tuxedo Orchestra in 1920; the Original Tuxedo Orchestra with Papa Celestin & Ridgley in ’21; and led his own and then Lawrence Marrero’s Original Diamond Orchestras in the early ’20s. He was one of three saxophone players on Papa Celestin’s first Tuxedo Band recording sessions, and then played with Jelly Roll Morton, Kid Howard at Lavida, and with Kid Rena before joining King Oliver in Kansas City in 1927. Oliver’s band had especially bad years in 1931 and then again in 1934-35–he also kept a diary of those years.

He returned to serious work on the clarinet once he joined the Navy, making rapid progress, advancing from Mus3c to Mus1c, but pointed out, “The prejudice was so strong here that you couldn’t go any higher than first class musician no matter who you were.” [The prejudice, in fact, was not particular to New Orleans but to the Navy’s rating of all Black musicians, who were kept from making Bandmaaster, which meant that virtiually all the Black bands had White bandmasters.] In the Navy, he also “learned to play the classics, operatic music and all that.” He taught clarinet some and played in a 16-piece band for Saturday night dances. Most of what they played, he said, was symphonic and classical and for parades.”

Barrnes stayed in New York for a while after the war, then returned to New Orleans. He composed “My Josephine,” recorded by Papa Celestin.

McNeal Breaux said that Barnes was the last person he knew still playing an E-flat clarinet: “Up until 1968 he played it in brass bands. I saw him play with the Eureka band one time and he played that E-flat clarinet.”

Thomas J. Brooks, Jr. trombone.

Originally from Tennessee, Brooks was sent to Algiers after training at Camp Robert Smalls: “They needed a trombone player in a hurry. I filled the bill–I could read and write music, so off I went. It turned out to be one of the greatest experiences of my life. I remember the good times we had off base, enjoying our liberty passes on Rampart Street and Bourbon Street. Our job was to play a weekly set for something called the “ships Company Dance for White Sailors.” But eventually they had dances for the Negro sailors as well. We played for them all, including picnics, commission ceremonies for new ships leaving the naval base and other social events for Navy men throughout Louisiana. One of my greatest thrills as a young man was the time the great Louis Armstrong came to our base and played with us.”

After his honorable discharge from the Navy on March 16, 1946, Brooks attended Tennessee State University, where he played with the Tennessee State Collegians Band. “We played Carnegie Hall [and] won a national contest as the best college band. We played the Savoy Ballroom in New York, and the football classics in Washington, DC, and we played all throughout the South.”

He earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in music education and taught at Tennessee State for 37 years.

William Casimir, clarinet, saxophone.

Bill Casimir was one of three musical brothers who grew up in the Humphreys’ neighborhood, where Jim Humphrey was one of their first teachers. John Casimir was a well-known clarinet player, and his interview with Richard Allen provides excellent information on the family background. “All my brothers play music, all my people play,” he told Allen. “My daddy used to play with the old pickwick band, you know, meolphony–peck horn, mellophone.” Their brother Sam played guitar in Chicago.

John Casimir said, “My brother Bill was one of the best tenor players they had. He used to work with Walter Pichon on the boat and quite naturally, he was out playing the neighhorhood every night, some little band.”

In Pichon’s band on the SS Capitol was Manuel Crusto, who served in the New Orleans Lakefront Navy band. After the war, Casimir played saxophone on a recording by Roosevelt Sykes and two by Eddie Boyd. Brother John Casimir, who led the Young Tuxedo Brass Band in the 1950s, claimed kinship to Marie Laveau and was generally thought to have a second-sight that allowed him to tell when someone was close to death, a gift he got from his grandmother.

Vernon B. Cooper (White), bandmaster, who is credited with having organized the band in 1942.

The Original Moonlight Seranaders, 1919-21, with Leo Dejan on trumpet, Harold Dejan (middle) on sax; Arnaul Thomas, drums; Henry Casanave, sax, Sidney Cates, banjo. Courtesy of the New Orleans Jazz Club Collection of the Louisiana State Museum

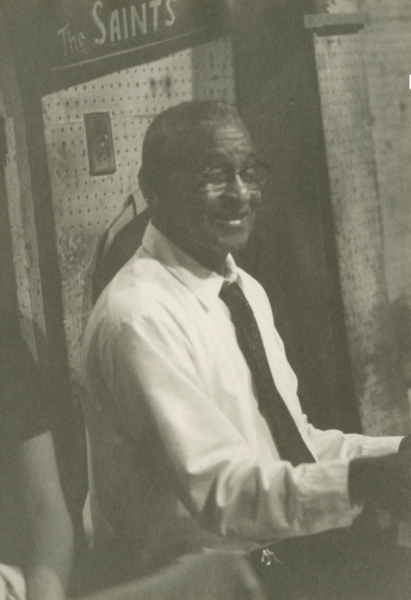

1967 photo of Harold Dejan. Courtesy of the New Orleans Jazz Club Collection of the Louisiana State Museum.

Harold Dejan, e-flat clarinet, saxophone.

One of the most beloved of all New Orleans musicians, Harold Dejan was born on February 4, 1909 and died on July 5, 2002.

Dejan was renowned as a performer, band leader, and friend to any in need. He led several small rhythm & blues groups in New Orleans and was in his brother Leo’s Moonlight Serenaders about 1918. He toured with the Joyland Revelers and Ridgley’s Tuxedo Band in the 1920s and then quit music briefly.

By 1929, he was playing locally and traveling with Clarence Desdune’s orchestra in a Model A Ford bus that Dejan kept at his Dumaine Street house. Dejan, who played tenor saxophone with Desdune, recalled having left Bebe Ridgley’s band to join Clarence Desdunes’ Joyland Revelers on the recommendation of Earl Fouché, who did not want to go out on tour.

In the ’30s he worked on the steamer SS Dixie, which sailed from New York to New Orleans, and the SS Ouchita on Lake Ponchartrain; in the ’50s, with the Young Tuxedo Brass Band and then as leader of the Olympia Brass Band (with fellow Navy bandsman Wendell Eugene on trombone). Dejan also led what Theodore Purnell called “the only Dixieland jazz band in the Navy” during World War II, comprised of players from the Algiers Navy band and others. Dejan, he said, “didn’t play anything he didn’t have to lay. When he got threatened with a transfer, he’d not play well until the officer who wanted him out had been transferred, then he’d play well again.”

Barry Martyn recalls meeting and interviewing Dejan in the documentary “Harold Dejan: A Sentimental Journey,” which is available on Youtube.

Sydney Dufachard, clarinet.

Frank Fields with the Dave Batholomew Band

Frank “Dude” Fields b. May 2, 1914. d. Sept. 18, 2005) , tuba, string bass.

Born in Plaquemine Parish, Fields started out with the legendary Claiborne Williams band in Donaldsonville, LA, and likely joined the Navy band with Claiborne Williams’ son, George A. Williams. After the war, he played with Papa Celestin and then became a principal session man at Cosimo Matassa’s J&M Studio. He recorded with Dave Bartholomew, Fats Domino, Little Richard, Professor Longhair, Smiley Lewis, Lloyd Price, Huey “Piano” Smith, and Ray Charles, among many others.

In 1965, he was playing with Albert French’s band and with the New Camelia Brass Band in the ’80s. He was named in 1990 to the Jazz All-Stars Honor Roll in New Orleans.

⊕

Cie Frazier at Preservation Hall 1975. Historic New Orleans Collection

Josiah Frazier (Feb. 23, 1904 – Jan. 10, 1983) drums.

Cie [pronounced Sy-ee] Frazier was born and lived on Touro Street in a neighborhood that included the musical Marrero, Bechet, Cottrell, and Barnes families. His father was a mattress maker and Baptist minister, his mother sang in their church choir, and his brother also played drums.

Cie Frazier played for many of the best known dance band leaders of the city, including A.J. Piron, Sidney Desvigne, John Robichaux, and Papa Celestin. He began playing professionally in 1921 with Lawrence Marrero, was in the Young Tuxedo Band in 1923, and worked in the ERA and WPA bands in the mid-1930s. He made his first recordings with Celestin in 1927.

He joined the Navy on September 4, 1942 with Henry Russ and Gilbert Young (who did not enlist in the band) and was discharged August 3, 1945. At Great Lakes, he showed bass drummers “how to play the New Orleans street beats.” William Russell recorded him with Wooden Joe Nicholas in May 1945, replacing Baby Dodds on a session at Artisan Hall.

He was with Papa Celestin again from 1950-52 and afterwards spotted with Percy Humphrey before joining the Sweet Emma Barrett band at Preservation Hall. He also played with Harold Dejan’s band. He went to Los Angeles with George Lewis and Earl Hines for a 6-week gig in 1956 and played with Kid Howard some on his return to New Orleans. Through the mid-1960s, he played with Harold Dejan, with Paul Barbarin his occasional substitute.

Listen to Cie Frazier drum!–courtesy of Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

Local musician and historian Barry Martyn talks about learning drums from Frazier in the documentary “I Had the Best Damn Teacher in the World,” which is available on Youtube.

Vernon Gilbert

Leon Harris

Gilbert Jones, trumpet.

John Jones

Reuben Roddy, alto sax.

b. Joplin, MO May 5, 1906; d. NOLA 1960.

Reuben Roddy was one of the most experienced musicians who enlisted in the Algiers Navy band, although the circumstances of his enlistment are a mystery. By the late 1920s he was with Walter Page’s Blue Devils; he played on their only two recordings. He also played with Benny Moten in Kansas City.

Roddy stayed in New Orleans after the war. He played with the Eureka Brass Band from 1946 into the mid 1950s and made several recordings with them. Jeff Crom notes, “Roddy’s New Orleans recordings show him to have thoroughly absorbed the New Orleans brass band and dance band styles.”

Henry Russ, drums, tuba, string bass.

b. NOA Aug 7, 1903.

Bandleader at dance halls in ’20s, w/ Peter Lacaze’s NOLA Band; in the Depression, he switched to trumpet and worked with WPA and ERA groups. He joined the Navy band with Cie Frazier.

Alexander William Spencer, horn.

Herbert Trist/Trisch, clarinet.

Booker T. Glass photographed by Betsy Burleson. Courtesy of Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University

Two Booker Washingtons

Booker T. Glass Washington

The Booker Washington identified in the group photo above is clearly not the same as the one pictured at right, who was born Booker T. Glass, in New Orleans on May 10, 1881 and died there on June 25, 1981. He would have been nearly 20 years too old for Navy service. Harold Dejan remembers Booker T. Washington, who also performed with him in the Great Olympia Band, as being in the Navy band, and said that he was re-named Booker T. Washington by the White doctor who adopted him.

Booker T. worked first making bricks and then as a plumber, telling Richard Allen in 1972 that he and a crew of 20 men “put in all that plumbing at the Algiers Naval Station,” so it seems likely that instead of serving in the Navy as a bandsmen, he worked on the base and played in outside bands with Dejan performing clubs and other civilian dates with the Gobs of Rhythm and other bands. He and his wife often took with them their pet alligator, Pete, to his shows, and they also were known for an unusual duck they kept as a pet.

Before the war, he had also played in at least one other band, led by Armand Piron, that included the New Orleans Navy musicians Eddie Pierson and Louis Barbarin, who served at the Lakefront station, and Bill Casimir, who served at Algiers.

Booker T. Glass’s obituary, June 26, 1981, archived by UPI:

NEW ORLEANS — Drummer Henry ‘Booker T’ Glass, a pioneer of Dixieland jazz, died Thursday. He was 101.

Glass, best known for his work with the Olympia Brass Brand died at his daughter’s home after a long illness.

Funeral arrangements were incomplete, but a traditional jazz funeral was being planned.

Glass was one of the last musicians whose development pre-dated the Dixieland style of the early 1900s.

‘His career goes all the way back to the very beginning,’ said Allen Jaffe, a tuba player with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band, who got his start with Glass.

‘He was the only one I know of who was still around who knew Buddy Bolden, generally credited with being the originator of Dixieland.’

Bolden and a handful of other New Orleans brass band musicians developed the swinging blues style at the turn of the century in the seamy saloons and brothels of the city’s fabled Storyville section.

Glass originally played bass drum and later acted as grand marshal for the Olympia Brass Band. He gave up in 1973 when his vision began to fail.

‘He was known as an incredibly powerful bass drummer,’ said daughter Bernadine Zardis. ‘He could march and play all day until he started losing his eyesight.’

She said Glass was remembered mostly for his colorfully costumed appearances at the city’s jazz funerals.

Booker Washington

The Booker Washington pictured in the group photo above attended Thomy Lafon Elementary School with Preston Jackson, Lee Collins, Joe Robichaux and Gideon Honore. Jackson recalled that he also played in Sidney Desvigne’s band.

Cie Frazier said that Booker Washington “taught a lot of the Navy musicians in Great Lakes how to play New Orleans-style parade bass horn.” He also taught local bassist and fellow Navy bandsman Frank Fields.

George A. Williams, trumpet (1910 – 1965), Donaldsonville, Louisiana.

Harold Dejan recalled that George Williams was the son “of the famous Claiborne Williams.” He taught music at Donaldsonville and was performing with his father’s band by the 1920s. By 1940, he was leading what had been his father’s band, and it included fellow Navy band recruit Frank Fields. It’s possible that one or more of the still-unknowns who served in the Algiers band also came from the Williams band.

Cie Frazier remembered that he was one of two principal arrangers with the Navy band. Roger Mitchell said he was “a fine sax player–an accomplished country musician” and that he played both piano and trumpet in the Navy band.He earned Mus1c, the highest rating a Black bandsman could attain during World War II.

Another George Williams

The George Williams who led his own brass band in 1950s New Orleans, pictured below, was born October 10, 1910, near Dryades and Third streets in New Orleans. He makes clear in an interview with William Russell that he is not the George Williams who was the son of Claiborne Williams; that George Williams was conducting a good band in Baton Rouge at the time of Russell’s interview, said New Orleans-George Williams.

At left, George Williams Brass Band parading at the corner of LaSalle and Josephine streets. Photograph by Ralston Crawford, 1958. Reproduced from the Jazz Archivist, the online newsletter published by the Hogan Jazz Archives at Tulane University.

At left, George Williams Brass Band parading at the corner of LaSalle and Josephine streets. Photograph by Ralston Crawford, 1958. Reproduced from the Jazz Archivist, the online newsletter published by the Hogan Jazz Archives at Tulane University.

The photo is part of a fascinating article, “Then and Now Photographs,” by Anthony DelRosario, who has combined his archival work with an excellent eye for the rare historic architectural treasures of New Orleans still standing, at least in 2012 when it was published.

• • •

Cie Frazier drumming at Papa John Joseph’s funeral parade. Courtesy of Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University

Sources

Alexander, Alphonse L. Interview with William Russell, Ralph Collins, Harold Dejan. New Orleans 8 Mar. 1961. Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

Barnes, Paul. Interview with Barry Martyn, Lara Edegran, and Richard B. Allen. New Orleans. 16 June 1969. Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

“Bertrand Adams” and “Hazel Poole Adams.” HT Faculty: Gatekeepers of Knowledge and Wisdom, Faculty of the Huston-Tillotson Legacy. storymaps.arcgis.com. Web. 21 Aug. 2022.

Burns, Mick. The Great Olympia Band. New Orleans: Jazzology Press, 2001.

Breaux, McNeal. Interview with Barry Martyn. New Orleans. 2005. Hogan Jazz Archive, Tulane University.

Casimir, John. Interview with Richard B. Allen. New Orleans. 17 Jan. 1959. Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

Chase, Dooky. Personal interview with author. New Orleans. Oct. 10, 2014.

Crom, Jeff. “Reuben Roddy: KC/New Orleans Saxophonist.” 16 May 2014. Jazz Forums. Organissimo.org. 8 Aug. 2022.

Dejan, Harold. Interview with Richard B. Allen. New Orleans. 29 Mar. 1963. Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

Dejan, Harold, with Els W. Velduisen. Everything Is Lovely: A Family Portrait. Pijnacker, the Netherlands: Holland Olympia, 1989.

Eugene, Wendell. Interview with Barry Martyn. New Orleans 4 Nov. 1999. Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

Fields, Josiah. Interview with William Russell and Ralph Collins. New Orleans 14 Dec. 1960. Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

Glass, Booker T. Interview with Richard B. Allen. 19 May 1972. New Orleans. Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

Glass, Booker T. Interview with William Russell. New Orleans. 2 Mar. 1962. Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

Hobbs, Holly. “Polo Barnes.” 64parishes.org. 2 Feb. 2013, 30 Nov. 2016.

Jackson, Preston. Trombone Man: Preston Jackson’s Story as told to Laurie Wright. Essex, England, 2005.

Koenig, D. Karl. Trinity of Early Jazz Leaders: John Robichaux, “Toots”Johnson, Claiborne Williams. basinstreet.com. n.d. web. 20 Aug. 2022.

Mike. “Here It Is.” Louisiana Weekly 19 Aug. 1944: 6;

—. 13 Jan. 1945: 6;

—. 28 Apr. 1945: 6.

“Naval Trumpeter.” [George A. Williams] Louisiana Weekly 20 May 1944: 1.

Newhart, Sally. The Original Tuxedo Jazz Band. Mt. Pleasant, SC: History Press, 2013.

Purnell, Theodore. Interview with William Russell. Feb. 3, 1961. New Orleans: Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

Rose, Al. I Remember Jazz: Six Decades among the Great Jazzmen. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1987.

Rose, Al and Edmond Souchon. New Orleans Jazz: A Family Album, 3rd ed. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1984.

“23 Musicians Inducted for Naval band.” Louisiana Weekly 15 Aug. 1942: 6.

Woods, David L. “New Orleans, La., Naval Station, 1803-1818; Algiers Naval Station, 1901-1933, 1939-1947; Naval Station, 1947-1966; Naval Support Activity, 1966-1983.” in United States Navy and Marine Bases, Domestic, Paolo E. Coletta, ed. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1985: 333-336.

“Thomas J. Brooks, Jr.” in A Little Known Legacy: The Great Lakes Experience: A Salute to African-American Navy Bandsmen at the Great Lakes Naval Base 1942-45 [Chicago, IL] [Feb. 2003]. Wray Herring Papers. Special Collections, Joyner Lib. East Carolina U.

The Algiers Navy band marching at an undated event. Courtesy of the New Orleans Jazz Club Collection of the Louisiana State Museum.

Tats Alexander, 1953, photo by Julian Smith Coswo. Courtesy of the New Orleans Jazz Club Collection of the Louisiana State Museum.

Booker T. Glass with second-liners, photographed by Betsy Hamden. Courtesy of Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

November 4, 2024