Bandsmen enlisted at the New Orleans Custom House, room 306, 423 Canal Street.

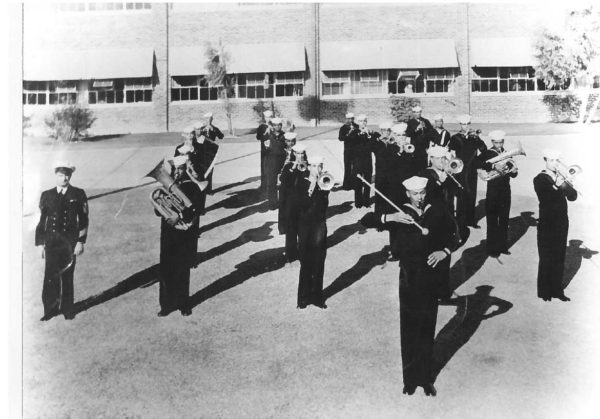

New Orleans’ first Navy band was assigned to the Lakefront Air Station, which was located near Elysian Fields and Lake Pontchartrain on property that is now the University of New Orleans. Formed with 23 New Orleans musicians who enlisted at the Custom House, it was also one of the first African-American bands recruited en masse and with a promise of service in their home territory for the war’s duration. The Navy had recruited Clyde Kerr’s locally popular orchestra, but not all in it could pass the qualifying tests. After their formal enlistment, the new recruits departed on August 10, 1942 for the Great Lakes Training Station in Chicago for what was announced to be two months’ training–the band was on duty at Lakefront less than five weeks later. “Many of the men are well known by local Negro night club patrons,” the Louisiana Weekly reported, “and the greater part of them are veteran musicians of long standing.” The Weekly added that “another Navy band would be formed within the next few days,” to be stationed at Algiers Naval Station, across the Mississippi River.

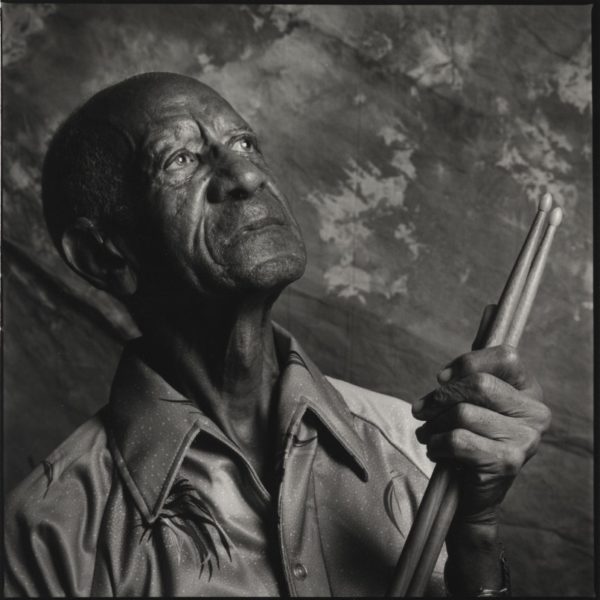

Wendell Eugene celebrated his 90th birthday on October 12, 2013, by performing at the Palm Court Jazz Cafe on Decatur Street. RAFoto.

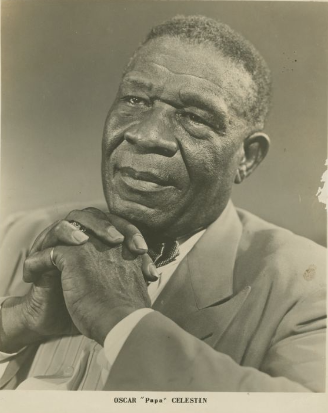

Wendell Eugene, who was playing with Papa Celestin’s band at the time, remembers recruiters coming to his house to discuss his enlisting. “They were trying to recruit musicians from different cities and states,” he told Barry Martyn in a 1999 interview. “So they contacted some of the old guys like Willie Humphrey–they were all of age. I had played with all of them and they liked my playing. Going in with a musician’s rating, I didn’t think they’d send me out on a ship or have me washing dishes, so I volunteered.”

Bandmaster Walter Knight came to New Orleans from the Navy’s School of Music to lead the band, but they were likely recruited by another White bandmaster, Vernon B. Cooper, who generally requested that potential recruits bring their instrument with them to his 306 Custom House office. Wendell Eugene recalled a battery of tests, including a sight reading exam. “They put two or three sheets of music out there and I played them,” he said. “One of the tests was hard–16th notes, syncopation, all that, just me by myself on the trombone. They told me I passed but you had to weigh 125 pounds to get in.” Because he was light and needed to gain “7 or 8 pounds,” he was told to “eat some bananas and come back, and I did and I weighed just that,” so he was accepted.

Eugene remembers the music tests as having been given about a week before formal enlisting, at which point, after passing a physical exam, “We left here and they put us on a train about 7 o’clock at night and we went to Chicago. Homer [his brother] brought me to the station. He gave me a bottle of gin, and on the trip, Clyde Kerr wanted a little sip, and then someone else wanted a little sip. We all sipped on that.”

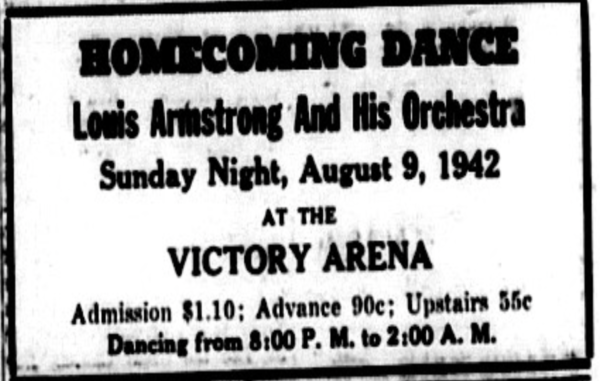

Most of the 23 Lakefront band recruits had, no doubt, been part of the weekend’s festivities that surrounded Louis Armstrong’s visit and performances on August 9, which were arranged by local promoter Louis Messina, who owned the Gypsy Tea Room and had recently begun promoting Black boxing matches at the Victory Arena (re-branded from the Coliseum). Prior to a show and dance there, he had been feted with a parade that wound up at the Gypsy Tea Room–also home to the Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club–where he was given a key to the city in a scene that “looked like carnival day,” and continued well into the morning of August 10, the day the Navy’s newest bandsmen’s left New Orleans for Chicago..

This was only the fifth time Armstrong had visited his home for performances since leaving for Chicago. Of the city’s three White daily newspapers, only the Item noted it, informally in a column by local ad agency executive Ken Gormin: “Tomorrow night he’ll raise his $1500 gold horn at the Victory Arena and show lovers of swing how it should be played. . . [He will play for]] both white and colored as he’s never played before, for Louis wants to ‘do it up brown’ and give Orleanians all the music his swing-infected soul can pour out.”

Certainly some if not all of the 23 young Navy recruits would have marveled, as they sipped on Wendell Eugene’s bottle, at how they were following Armstrong’s own path, almost 20 years prior to the day, August 8, 1922, when he left New Orleans for Chicago? Surely they had been among the crowds who celebrated Armstrong’s homecoming–several had performed onstage at the Gypsy Tea Room and would continue to do so during their Navy tenure, and it would seem a fair to guess that among them would be some who’d have sat in with the Armstrong’s band at the GTR that evening On one of his subsequent visits, he and his band would also perform for the Algiers Station Navy band.

None of the White press noted the Navy bandsmen’s departure: Local news in the Item, the States, and the Times-Picayune that weekend included reminders of a Sunday pleasure-driving prohibition and the beginning, at midnight on August 10, of a ban on selling alcohol to men in uniforms daily from midnight to 7 a.m.

Louisiana Weekly, Aug. 8, 1942: 6

The core of the original Lakefront band came from what Jack Buerkle and Danny Barker termed “Bourbon Street Black,” a music and family-centric extended Black community that produced countless musicians like Barker, Clyde Kerr and Wendell Eugene and even more music lovers and supporters. Buerkle and Barker define Bourbon Street Black as a “semi-community in New Orleans of musicians, their relatives, peers, friends, and general supporters, whose style of life is built around the fundamental assumption that the production and nurture of music for people, in general, is good.” They explain that this “intensely shared style of life” came from a core of professional musicians from a few core families, many of whose families had been “involved in Bourbon Street Black for four or more generations” as performers and teachers. The core families are predominately Black, but not exclusively so, and Bourbon Street Black “membership” remains open to any who “involve themselves deeply in the Black musical styles of New Orleans, particularly traditional jazz. Usually, to the extent that it is possible, they live Black.” Non-musicians and Whites are welcome in this informal fraternity, once “it becomes apparent to at least some in the core that they have a major emotional (and sometimes professional) commitment to the scene.” These include writers, researchers, critics, and jazz buffs.” Their involvement, however, “is usually not as intensive, or extensive as Black members’,” and tends also to be “transitory.”

The community proved over and over that it was glad to welcome into it musicians who moved to New Orleans and who took up their “intensely shared life.” In the early 1970s, Buerkle and Barker estimated Bourbon Street Black had between 400-500 core members with another 1500-2000 on the periphery, about 1% of the city’s Black population. Not only did most of the first New Orleans Navy bandsmen come from these core families, several were still active in the city when Buerkle and Barker published their book.

Papa Celestin’s Original Tuxedo Band included 2 future Lakefront Navy bandsmen, Bill Matthews at left and Louis Barbarin, 4th from right. Courtesy of Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

“There were sections of New Orleans that spawned whole bands,” Al Rose writes in I Remember. Local bandleader Joe Robichaux told him that he didn’t have to leave his neighborhood to put together his swing band. Rose identifies five such predominately Black neighborhoods: one, with part in the Faubourg Marigny and the rest “spread all the way back to the Industrial Canal toward Chalmette,” was home to Sidney Bechet’s family as well as Willie Guitar, the Baquets, “and dozens of others”; a 2-block uptown neighborhood around First Street and Simon Bolivar that was home to King Oliver, Kid Ory, Buddy Bolden and Wallace Collins; the Treme, home to Kid Rena, Alphonse Picou, the Morgans, Keppards, and George Lewis; the Perdido Street/ South Rampart neighborhood where Louis Armstrong, Johnny and Baby Dodds, and Punch Miller developed; and “what we always called the ‘Creole Section,’ roughly bounded by Esplanade, Elysian Fields, Claiborne Avenue, and North Broad Avenue.”

Don Albert grew up in a Creole section where his neighbors and mentors included the leaders of the Onward and Excelsior Brass Bands, a couple of legendary teachers, Danny Barker, and his cousin, Barney Bigard. Chris Wilkinson, in his biography of Albert, asserts that during the first two decades of the twentieth century music was as ubiquitous in New Orleans as it had been in West Africa. He was specifically referring to Don Albert’s Robertson Street neighborhood, but he could as easily have extended his range to include the other music-centric neighborhoods. “Music,” he adds, was part of “all the culture, dawn to dusk, marking the stages of life along the way.”

Willie Humphrey & McNeal Breaux were still playing together in 1961, here recording with Sweet Emma Barrett’s band & photographed by Ralston Crawford. Courtesy of Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane U.

At least 17 of the original 23 Lakefront bandsmen, with surnames of long-time local musician families, were a part of the Bourbon Street Black community: Leo Dejan, William Matthews, Manuel Crusto, Theodore Purnell, Wendell Eugene, brothers Carey and Michael Lavigne, Willie Humphrey, James Ursin, Jr., Louis Barbarin, Raymond Glapion, Eddie Pierson, Clyde Kerr, McNeil Breaux, Sr., and Wendell Eugene,

Several of the others had come to New Orleans for work in bands prior to the war: Fred Darnes, Robert Johnson, Joseph Brown, William Drake, Ernest E. Bridges, Earl Joseph, and Froebel Brigham. From Arkansas, Brigham had been performing–like many of New Orleans’ best players of his generation–with Papa Celestin.

Drake, from Oklahoma, had somehow become a resident of Wendell Eugene’s neighborhood, where he easily qualifies as part of the Bourbon Street Black community. But whether he came to the city for work, to visit family, to vacation, is unknown. Bridges was an aspiring journalist as well as a musician when he graduated from Alabama State, but again, how he wound up in New Orleans is unknown.

It’s tempting to guess that all the non-local bandsmen came to New Orleans because of the city’s well earned reputation as a good place for live music, but the renown of its jazz scene had waned nationally during the 1930s. By the tine World War II broke out, a revival of sorts was under way, and when the Lakefront band was formed in August 1942, music was being performed live in New Orleans in countless venues and by an untold number of musicians. The city’s Black community made and enjoyed music in increasingly more public and popular fashion: celebratory and funeral parades; battles of the bands, dances and festivals, both public and the many sponsored by fraternal orders, social and pleasure clubs; and by street bands and singers and bar room piano players. Over 85 Black churches held weekly services, many with additional concerts: what music did they make? Recitals by public and private school and academy students are noted regularly in the Louisiana Weekly. Traveling performers booked for clubs or special dates at larger venues or the auditoriums at Xavier University and the new Booker T. Washington High School. And as the military presence grew, so did the music scene, with bands established not only at Lakefront but at the Algiers Naval Station, the Coast Guard station, and at Jackson Barracks. All kept active public performance schedules.

Parades and bond rallies were the most public occasions the military bands played for; those, too, were segregated in their ways: the Chicago Defender terms one a “Jim Crow” parade for including only two Black units, the two Navy bands, and the bond rally parades for the Black community stayed in Black neighborhoods, with little notice from the White world, none from its press but for an occasional tally of what had been pledged.

The Lakefront band returned home from their Great Lakes training on September 12, 1942 to a city already teeming with band music: municipal, military, school, recreational, fraternal, community and corporate bands–Higgins Boats, for example, had a 125-piece band that performed at ship launchings, parades, and special occasions. The police department’s band gave its last concert of the season at the City Park stadium, for 4 hours on September 13. Though the last three of four WPA bands were closing down operations, they still performed regularly into November 1942 multiple concerts, often daily. Of the military bands, the Coast Guard band, directed by Freddie Neuman, was the best before the Lakefront band arrived. Of the high schools, Alice Fortier’s Military Band got the most press. One of four recruits from that band told the Times-Picayune, “We’ll jive for the Navy, too, if they’ll let us.”

The Fortier students were part of at least one White band recruited locally, and a second was sought. When announcing a second call for Negro musicians on August 16, 1942, local recruiter and bandmaster Vernon B. Cooper also said the Navy was in need of “another White band.” A month later, he announced the induction of the Black band that would be stationed at Algiers, and that he would tour eight Louisiana cities to audition musicians for that second White Navy band. He was still looking for his quota on September 24.

Events off-base at which the Lakefront band played during the fall of 1942 were most often associated with bond rallies and recruitment drives as the Navy continued to push its advantages: all volunteers, all specialists, “sign up all the way up to the minute of your Army draft induction.” But programs for these events are difficult to re-create, and newspaper accounts are clearly incomplete. Still, among the bigger events likely to have featured the Lakefront band were a September 27 celebration of the launching of the 15th Liberty ship at the shipyard on Canal; an October 27 Navy Day flotilla and address by Gov. Jones (the Coast Guard band was selected to play for advancing of the colors); and a November 1 war bond parade and meeting (originally scheduled the previous Sunday but postponed because of weather), with “Negroes to gather at the Autocrat Club” in the Calliope Housing Project. The following Sunday, November 8, a White bond rally and parade with over 7,000 marchers kicked off at 2:30 p.m., while a Black parade began at 1 p.m. The Armistice Day parade, on November 11, a Wednesday night, was staged at night to make it more Carnival-like.

Like most other Navy bands, work for the Lakefront band was primarily a day job. The New Orleans Item reported that they performed “during the impressive ceremony of raising colors each morning, pounding out the marching beat for the drills of the instructors under training and every Saturday night jiving out for the station dance.” After lunch, if they didn’t have a job somewhere, they practiced, and at 5 p.m. they were done for the day.

Like most other Navy bands, work for the Lakefront band was primarily a day job. The New Orleans Item reported that they performed “during the impressive ceremony of raising colors each morning, pounding out the marching beat for the drills of the instructors under training and every Saturday night jiving out for the station dance.” After lunch, if they didn’t have a job somewhere, they practiced, and at 5 p.m. they were done for the day.

The lack of accommodations at Lakefront for African Americans provided Eugene and his mates with a bonus: “They paid me to go home at night,” he said. “They didn’t want Blacks staying on the base, so they paid us off, a 23-piece band, to all go home. We were glad of it because money was kind of slow. We got $100 a month extra to live at home. Subsistence, they called it, plus our salary, and I was living with my mother.”

“Every morning we had to report at 7 a.m.,” Eugene said. “They used to pick me up at a bus stop about seven blocks from my house. They picked up the whole band. I was the last one they picked up. I was the closest to the base, me and Bill Drake, who lived a street over. We’d walk to the bus stop together, but when Homer [his brother] went into the service, I got his car, so I’d pick up Bill Drake.”

In addition to their performances for bond rallies and parades, bandsmen also played for dances and parties. Whereas Lakefront appears to have been the standard 23-piece Navy band that marched and performed concerts, with a dance band of about 12 pieces (one news report says the Lakefront’s dance band was a 15-piece), the two in New Orleans also had Dixieland jazz bands. According to Eugene, the Lakefront Dixieland jazz band played primarily at the officers club. It was a Bourbon Street Black band, with Wendell Eugene on trombone, Manuel Crusto on trumpet, Louis Barbarin on drums, McNeal Breaux on bass, Willie Humphrey on clarinet, and Raymond Glapion on guitar.

With the dance band, Eugene remembered, “We played for a Black dance about once a month and we played for some dances at the base across the river. Sometimes we’d play a football game, a baseball game. We played in the auditorium for enlisted men.” The band also escorted dishonorably discharged sailors off the base. Eugene recalls this happening four or five times, though only once to someone he knew–not a bandsman but another fellow accused of stealing. “We played them off the base,” he said. “Louis Barbarin would play the snare drum, and we marched along with him, marched them out to the gate. All he played was cadence, and we marched along. They’d give ’em a suit of clothes and $15 and push ’em out.” Although it was frowned upon by the Navy, some fellows also played gigs at night. Eugene played Wednesday and Sunday nights at the S&J on St. Bernard. “It was a White people’s bar,” he said. We’d get $5 a piece plus tips.” He also performed once at the Gypsy Tea Room, in uniform: “Somebody reported us. They called us to captain’s mess and said we heard you boys played outside last night. We said we didn’t know we couldn’t do that. They said you can’t do that.” So subsequent gigs, primarily at the S&J, were done in civilian clothes.

One disadvantage to playing in the Navy’s official dance and Dixieland bands was that everyone else went home each night at 5 p.m. “We didn’t get any extra money [for playing official Navy evening dances and other night-time events],” Eugene said. “James Ursin, he got to go home every night.”

For Eugene, the Navy was a valuable musical experience because of the discipline it taught, and for its emphasis on reading music. “Willie Humphrey was a good reader,” he said. “Manuel Crusto, he was a good reader but he didn’t have the lips to play the high notes. Alton [Fournier] was a pretty good reader, too.” The secret to learning to play high notes, he said, was to “keep on going, holding your notes. That’s what they had us do in the Navy, practice holding notes. That’s the best way to learn. My best practice was in the Navy.” Every year they were together, Eugene recalled, because he was the youngest in the band, he posed as the New Year during one opposite Willie Humphrey as the Old Year.

Saxophonist Theodore Purnell said that the Navy band he played in with Clyde Kerr at the Lakefront air station was the best band he ever played with. Wendell Eugene agreed with McNeal Breaux’s recollection that Kerr and Michael Lavinge were its principal arrangers. “Clyde wrote advanced harmony,” Breaux told jazz historian Barry Martyn in a 2005 interview. “But Chief would scratch it out if it went past the 7th.”

Breaux said he and Chief Bandmaster Walter Knight had major conflicts: “He’d say ‘why the hell can’t you play what you see?’ I don’t know how he got to be bandmaster.”

Knight, like all rated bandmasters during the war, was White. “He said I had a bad attitude,” Breaux recalled. “I said, ‘Naw, if I did, I’d be knocking on your head.’ [U.S. Navy B-1 had an African-American leader, James B. Parsons, but he never attained rank of bandmaster] and the Navy twice tried unsuccessfully to put White bandmasters in charge of his band. Parsons’ highest rating was Mus1c.] “He said ‘With your attitude, you’ll never make stripes.'”

“I said, ‘You can’t fire me and I ain’t going to quit.'”

It took a new chief being named to the base for Breaux to get his second stripe, which was worth another $100 per month.

Wendell Eugene recalls a similar conflict: “In the marching band, we rehearsed every morning. Chief Knight, he was over the band, and he wasn’t nice to me at all. At certain times, some guy would mess up. The second trombone, he was a beginner, and the other one would miss occasionally, too, not play a part right. Every time somebody made a mistake, Chief’d jump on me. He’d look at me, tell me how it’s supposed to go. This went on for months–it was always me. The second trombone and the other one, he’d never tell them anything. So, I went in to see him one day to see what I was doing wrong. We had guys couldn’t play, I don’t know how they passed the music tests. So the chief said ‘I’m going to tell you: I don’t like you. As long as you’re under me, you’re not going to get a rating’ [promotion to Musc2c]. He gave the 2nd trombone player the rating. Never did get one till I got a new chief.”

Identifications of band members in the photo above have been made by Barry Martyn.

Far left: Chief Walter Knight.

In rows from left to right and front to back

First row: McNeal Breaux, Raymond Glapion, Leo Dejan, E.E. Bridges, unidentified.

Second row: Bill Drake (from Oklahoma), Clyde Kerr, Sr., unidentified, unidentified, unidentified.

Third row: Eddie Pierson, Frog Brigham or Fred Dawns, Manuel Crusto, Carey Lavinge (?), Theodore Purnell.

Fourth row: Wendell Eugene, James Ursin, Frog Brigham or Fred Dawns, Louis Barbarin, Willie J. Humphrey. Drum major: Oliver Dixon.

Louisiana Weekly, April 20, 1940

Clyde Kerr’s orchestra, from which many of the bandsmen came, was a big band. McNeal Breaux recalled: “Just before World War II, he had one of the best aggregations in the city. We had every Sunday afternoon on the Tick Tock, and the majority of the night dances, except when they had out of town attractions. But every matinee we had it on the TickTock. Oh, he had a big band! Dave Bartholomew on trumpet, and his younger brother who has deceased since, was killed in Chicago, and I think he had three trombones up there too; he had about six brass, and about five or six reeds, and full rhythm at all times, piano, bass, guitar, and drum.”

Kerr was a natural, then, as leader of the swing band that formed out of the larger Lakefront band. The Shipmates of Rhythm featured the base’s best musicians, and a smaller dance band, called the Salty Seven, was popular at officers’ socials.

Kerr continued to publish songs while serving in the Navy and also composed music for the Shipmates of Rhythm, whose assistant director was Leo Dejan, Mus1c. Both the Shipmates of Rhythm and the Salty Seven made recordings for the Navy, some of which were likely for “Skyway to Victory,” the Shipmates of Rhythm’s weekly radio program, which aired on WWL Fridays at 9:30 p.m. “We cut a lot of records for overseas,” McNeal Breaux says, “but like I say, they wasn’t for sale, they were strictly Uncle Sam’s business” of entertaining troops. Some performances on what the Bayou Tale Spinner called “one of the nation’s top-ranking service shows” were behind featured singers. Breaux remembers Robert Taylor emceeing some of the shows; while stationed at Lakefront, Taylor also served as a flight instructor. The band was so good that on some occasions it was the sole feature, performing original Kerr compositions such as “Victory Bounce.”

The Weekly notes that in order “to give music that hot or sweet rhythmic effect so necessary to dance music, most of the numbers played by the band have been arranged by members of the group.” Other popular tunes performed by the band were Carey Lavigne’s compositions “Sailor Boy,” “Lovers of Liberty,” and “Boot Camp Jive”; “Clyde’s Jive,” composed by Kerr; and “I’ve Found the One Who Loves Me,” composed by Ernest E. Bridges.

The Item reported that the Shipmates of Rhythm also presented daily jam sessions in the hangar during lunch break for pilots and enlisted men who were working on the planes: “Many a flyer has been known to zip his plane through maneuvers snappily and smartly after hearing a hangar-rocking rendition of the “Two O’clock Jump.’” The Shipmates also played swing concerts for those in sick bay and for happy hour programs and talent shows.

The Weekly recognized the band’s first anniversary at the Lakefront station in August 1943 with a photo and front page article that listed the band’s personnel. Bandsmen included who were not among the first recruits included Fred Darnes, Eli Johnson, and James Brown. Those listed in the original band but not as part of the band in August 1943 were William Matthews, Joseph Brown, James Ursin, Jr., Oliver Dixon, and Thomas Johnson.

Dooky Chase explains what it was like to play a Battle of the Bands against Clyde Kerr’s Navy band.

Dooky Chase recalls his band playing a battle of the bands against Kerr’s Navy swing band in the Gypsy Tea Room. Chase, who was 15 when he organized his first band, said his band benefited greatly by so many local players having joined the Navy, leaving fewer bands to fill gigs about town. After the war, he hired several former Navy musicians to play with him.

• • •

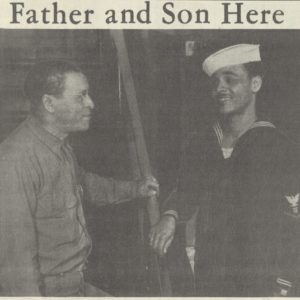

Wendell Eugene with his father

In November 1944, the base magazine, Bayou Tale Spinner, ran this photo, at right, of Wendell Eugene and his father, Homer Eugene, Sr., who was a porter in the Algiers base instructors school, and notes that three other Eugene boys are in the military: Sgt. Homer Eugene, Jr., with the Marines at Camp Lejeune (his posting was most likely at the nearby Montford Point, which was the first Marine base for African-Americans); Sgt. Adrien E. Eugene, who was in France; and S/Sgt. Lehman C. Eugene, who was at Camp Stewart, Georgia.

E.E. Bridges wrote a regular column for the Tale Spinner, “Coloredata,” that was targeted to the base’s Black population. He reports that bandsmen James Ursin and Manuel Crusto were outstanding in a double-header win by the base’s Black baseball team; Michael Lavinge is the top pool player and Robert C. Johnson the best ping-ponger; and Froebel A. Brigham, a 4-letter man in sports at Southern University and Arkansas State, was assistant coach to the basketball team.

The band stayed at Lakefront for over a year before being broken up. Members were then sent back to Great Lakes for re-assignment, an experience that mirrors that of other Black Navy bandsmen who were promised duty for the duration at one station only to be shipped elsewhere. Personnel in the second Lakefront Navy band is unknown; they were replaced in 1945 by a third band that included Lou Donaldson and his Greensboro, N.C. buddy Carl Foster, among others.

Crusto told Al Kennedy that this band was broken up once it was realized they weren’t supposed to stay together. He also told Kennedy about an incident that he said got the “colored” signs removed from the base mess hall and himself nearly arrested.

After the band was broken up, Kerr and some of his band went back to Camp Robert Smalls in Chicago, where Kerr led the Ship’s Company Band A for a brief period; members of his orchestra included Clark Terry and Marshall Royal. Royal would become a leader of the band attached to the Navy’s PreFlight school at St. Mary’s College. Other New Orleans bandsmen in the Bay Area were Alvin Alcorn and Willie Humphrey, who also wound up at the St. Mary’s PreFlight School, where he got picked up by the second dance band because its leader, Marshal Royal, didn’t know who Humphrey was.

After New Orleans, Lavigne and Eugene were sent to Port Chicago, where they were stationed when the July 17, 1944 explosions sank one Liberty ship and killed over 200 African-American dockworkers; 208 Blacks were subsequently court-martialed.

Little is known about the band that replaced the first one at Lakefront Naval Air Station. Its replacement, Navy Band 757, was the last band posted there.

• • •

New Orleans is prominent in Navy history as the site of the famous battle during the War of 1812 in which a small flotilla of American gunboats, aided by the pirate gun ships of Jean Lafitte, assisted Gen. Andrew Jackson in defeating the British. That battle is significant, too, for African-Americans; before it, Blacks were officially excluded from service in the U.S. military, but Jackson’s desperate need for manpower necessitated the creation of the Louisiana Free Men of Color. His address to those troops before the Battle of New Orleans is remarkable: “Through a mistaken policy you have heretofore been deprived of a participation in the glorious struggle for national rights in which our country is engaged. This no longer exists.” Jackson, however, was wrong; the “mistaken policy” was still in place and would remain in place until the Civil War, and variations of it would persist through World War II.

The Navy had a station in New Orleans from 1803 to 1818 but its first building activity was the construction of a dry dock commissioned in Algiers, across the river, in 1901. Until the Lakefront station was built, Algiers Naval Station was the only Navy operation in the city.

The New Orleans Naval Air Station at Lakefront was started on a 182-acre tract deeded by the city to the Navy on the shores of Lake Pontchartrain, where it had been the site of an amusement park. It was first commissioned, on July 15, 1941, as a Naval Reserve Aviation Base and later became a primary flight training school as well as a teacher training institute charged with preparing flight instructors. In September 1945, it became the headquarters air station for Naval Air Bases Command, Eighth Naval District, which was transferred from Charleston, and also a Naval Personnel Separation Center. It was decommissioned in 1957 and its operations moved to Callender Field, across the Mississippi River in Belle Chasse. The University of New Orleans campus now occupies the land where the air station was located.

Muster list of musicians who played with the first Lakefront band:

1993 photo of Louis Barbarin by John McCusker, Times-Picayune, courtesy of the Collections of the Louisiana State Museum. Gift of John McCusker and Times-Picayune

Louis Isidore Barbarin (Oct. 24, 1902 – May 12, 1997) drums.

Louis Barbarin was the son of Isidore John Barbarin, who played cornet in the Arnold Brass Band with his uncle’s brother, Louis Arthenol on clarinet. Louis was one of four brothers, all born at Columbus and St Claude Avenue in New Orleans. Although his older brother, the drummer Paul Barbarin, is remembered more today, Bob French considered Louis Barbarin “the king. . . the greatest drummer of all time.” Their brothers William and Lucien were also musicians.

Louis Barbarin recalled hearing Louis Armstrong performing at the Waif’s School while Armstrong was still a child living there. He played in bands as a teenager and by 1923 was with the Imperial Serenaders. When the Serenaders’ leader, Albert Snaer, left, Sidney Desvigne came to New Orleans from St. Louis and the band soon became his Southern Syncopators, which would remain one of New Orleans’ most popular dance bands through the 1940s. Barbarin started playing with Papa Celestin in 1937 and went back to Desvigne’s band before joining the Navy. After the war, he went to New York with Danny Barker, then joined a USO show, rejoined Desvigne’s band until 1950, then went back with Papa Celestin. He also played with the Onward Brass Band along with fellow Navy bandmate, from Algiers Station, Adolphe Alexander, Jr.

Warren Bell, alto sax.

McNeal Breaux

McNeal Breaux (Aug. 11, 1916 – 2002), upright bass and bass horn, New Orleans. He was born “on Josephine and Willow, “right next to Mrs. Hebert Cole’s house. ”

Breaux told interviewers in 1958, “When I first started playing music was right there on St. Peter Street with Professor Middleton, and I started playing drum.” Because he was big for his age, Middleton suggested that he switch to bass horn; his mother bought his first one from Werlein’s for about $50.; he later picked up bass and would play each throughout his long New Orleans music career (drums or horn in parades, upright bass with ensembles), often with fellow Navy buddies, especially Willie Humphrey and Cie Frazier.

His first band, the Crescent City High Hatters, was formed with friends in the Treme, and they played together for 2-3 years. before Breaux joined Bill Phillips’ Dixie Syncopators. “I played with practically every local band in this territory,” he said, and then listed a few: Joe Robichaux, Paul Barbarin, Henry Harding, Kid Howard, Kid Rena, and Clyde Kerr. He also played with Isiah Morgan’s orchestra; “Red Allen’s daddy’s band, across the river”; Cato’s trio; and the Johnson Brothers, Raymond and Plas (whose mother sang on Bourbon Street); and recorded “a few songs” with Fats Pichon: “I don’t think they sold.” He had his own band on Bourbon Street for several years, before joining Paul Barbarin’s at the Paddock Lounge.

Breaux vividly recalled several early New Orleans musicians, not all of whose identities are complete. Peter Locaze had the best tone on bass horn, he said, “he used to make it ring out.” Manuel Manetta described how powerful Locaze was: “Remember how he used to make all that noise when he’d blow them pickets out of them fences there? Man, he’d pass by Old Featherhead’s there, and blow there and knock the fence down1”

As a youngster, Breaux also enjoyed sneaking into the Artistocrat Club to see Joe Robichaux’s orchestra, especially the drummer, remembered only as Buckets, who was “more pigeon-toed” than Robichaux and “had a lot of novelty with him, you know–stick tricks and all that kind of stuff.” He was also so short that he never sat on a stool, but leaned on it as he played.

On the piano player known as Burnell: “Could he play? Good gracious alive! Burnell had such a keen ear he could work in anybody’s band, and I don’t care what kind of modulations you’re making he’ll change key right along with you like he was reading. I recall one time, I think it was on the Pelican, that Earl Hines came down, and he and Burnell got tied up there in a piano contest and he gave him a draw. He really was great.”

In 1958, Breaux lamented how hard it was to find work as a musician, because rock and roll had “got things sewed up so bad.” He added: “For what you call stomp-down jumping, a good Dixieland band, you just can’t get around it, because you always have that absolute beat, and that’s very essential with that type of music.”

Fro Brigham, 1970s, San Diego. From California Soul: Music of African-Americans in the West

Froebel Astor “Fro” Brigham, trumpet, Magnolia, Ark.

Brigham was working in a CCC camp when he read that the Navy was recruiting African-American musicians. “They made me a recruiting officer for the New Orleans-Baton Rouge area,” he recalled. “We had to learn Navy ways; thereafter we returned to New Orleans.” Prior to joining the Navy, he had played with Papa Celestin, and he had an interest in traditional music early on: “In the barracks some of us would sit around and talk about preserving 100 years of music. . . I named my band [in New Orleans] Preservation, attempting to preserve the good songs of yesteryear and the good ones of today.”

Brigham, from Magnolia, Arkansas, married Pearl Inez Barnes of New Orleans at Trinity Methodist Church in New Orleans in December 1943. Their wedding announcement notes that he was a student in physical education at Southern University prior to enlisting, and prior to moving to New Orleans, at Arkansas State, where he was a 4-sport letter-winner. He was the only bandsman on the base’s Black basketball team.

After the Lakefront Navy band was broken up and its members returned to Camp Smalls, Brigham had a choice of going to San Diego, Boston, or Norfolk: “Being a country boy, I didn’t know too much about California; however, I chose San Diego because the weather was cold in the other cities.”

That was in 1945: “Once established in Point Loma, I began to come to town and get acquainted.” He earned his early reputation working for Troy Floyd at his Creole Palace in the Douglas Hotel and was recruited to form its house band. He regularly drove to Los Angeles to pick up performers such as Redd Foxx, Errol Garner, Jimmy Reed, and Big Joe Turner for performances that his band would accompany.

He also called his band in San Diego the Preservation Jazz Band, which he led for over 30 years, playing with a mouthpiece given him by Louis Armstrong. For over 20 years, he also played regular Friday and Saturday night gigs at Pal Joey’s in the Allied Gardens and on Wednesday and Thursday nights at Patrick’s II in downtown San Diego. His late night gigs at the Creole Palace included Harold Land on sax; Billie Holiday, Count Basie and Duke Ellington were among the performers who played there after their regular shows in San Diego. Brigham won two San Diego Music Awards and was honored in 1993 as “Grandaddy of San Diego Jazz” by the Catfish Club. He was once flown by Lady Bird Johnson to her ranch in Texas to perform.

He worked as a groundskeeper for San Diego Parks and Recreation from 1949-79.

Earl Ernest Bridges, piano, bass drum.

Bridges was a graduate of Alabama State and the Newspaper Institute of America. He played piano in the dance band and bass drum in the marching band. He also wrote a column, “Coloredata,” for the base newspaper, the Bayou Tale Spinner, that debuted in the April 22, 1944 issue and noted that the number of “colored enlisted has increased considerably”.

James W. Brown, saxophone.

Brown was a graduate of Jackson College.

Manuel Crusto, trumpet, New Orleans.

Crusto, who also played clarinet and saxophone, was born in New Orleans on May 2, 1918. He played with Fats Pichon on the SS Capitol in the 1930s and ’40s and played often at Heritage Hall and Preservation Hall. After the Lakefront band was broken up, he was sent back to Camp Smalls in Chicago for re-assignment. In June 1945, he and fellow bandmates Clyde Kerr and Leo Dejan were sent with a newly formed band, with Kerr as its leader, to the naval station at Treasure Island in San Francisco Bay, where he served until the war’s end.

Fred Darnes or Dawns, trumpet, New Orleans.

Leo Dejan at a 1982 jazz reunion. Courtesy of Tulane University Digital Archives.

Leo John Dejan, Jr., trumpet, assistant bandmaster, New Orleans.

Born in New Orleans on May 4, 1911, Dejan began playing violin at 7, at 14 had his own band, and at 15 was leading the Moonlight Serenaders. In the ’20s, he led the Black Diamond Orchestra.

He began studying pharmacy at Xavier University but was persuaded by a college dean to change majors to music. He graduated from Xavier in 1933.

With the Navy band, he earned Mus1c rating, the highest given to African-American bandsmen during World War II. The Louisiana Weekly said that he was “largely responsible” for the development of the Lakefront band.

After the Lakefront band was broken up, he was sent back to Camp Smalls in Chicago for re-assignment. In June 1945, he and fellow bandmates Clyde Kerr and Manuel Crusto were sent with a newly formed band, with Kerr as its leader, to the naval station at Treasure Island in San Francisco Bay, where he served until the war’s end.

Oliver W. Dixon, drum major, flute, Jackson, Mississippi.

Dixon was a graduate of Alcorn College. Wendell Eugene recalled that Dixon was a good drum major but only held his flute in a playing position when they marched: “He never did play it.”

William Drake, trombone, Oklahoma.

Wendell Eugene, trombone, New Orleans.

b. Oct 12, 1923 d. Nov. 7, 2017

The youngest of five sons born to Homer Eugene and Apah Burbank Eugene on October 12, 1923, he is remembered by Dooky Chase as the best trombone players of his time. Eugene was in Chase’s dance band after World War II ended. “He was one of the best trombone players in the country,” Chase told Tad Jones and Jack Stewart in a 1999 interview. “He could play the high part when the other trombone player couldn’t play it.”

Eugene played with the Don Raymond and Kid Howard bands before joining Papa Celestin’s about 1940. “Celestin was working [a day job] with the WPA with my father digging ditches,” he said, “and he needed a trombone player.”

After Dooky Chase’s band broke up in 1946, Eugene played with Lucky Millinder’s band, Celestin’s orchestra off and on for years, the Olympia Brass Band for about seven years, and others.

He recorded “When the Saints Go Marching In” in 1952 in a band that included fellow Navy bandsman Willie Humphrey.

Watch the two of them performing in a French Quarter club band in the 1950s–nearly 12 minutes of great vintage film.

Alton Fournier [?], alto saxophone, clarinet, New Orleans.

Raymond Glapion, L, and Eddie Dawson. Photo by Ralston Crawford. Courtesy of Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University

Raymond Glapion, guitar, French horn, New Orleans.

The Raymond Glapion who was born in New Orleans about 1895 is, perhaps, the father of Raymond Glapion who played in the Algiers Station band. During World War I, the older Glapion played with orchestras at the lakefront resorts, primarily with the Gaspards and Paul and Emile Barnes and was in Polo Barnes’ dance orchestra in 1932.

Robert H. Holland, tenor sax and clarinet, Dayton, Ohio.

Holland played with the Wilberforce College Collegians prior to joining the Navy. He was a replacement bandsman sent to New Orleans, transferred in from the Olathe, Kansas Naval Air Station in July 1944.

Willie Humphrey & Thomas Jefferson at the Mardi Gras Lounge. Photo by Ralston Crawford. Courtesy of Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

Willie James Humphrey clarinet, New Orleans.

b. Dec. 29, 1900 d. June 7, 1994

As long time clarinetist with Sweet Emma Barrett at Preservation Hall, Willie Humphrey has been heard by countless thousands of tourists without knowing the depths of his musical pedigree. He was the oldest of the Humphrey brothers, one of New Orleans’ many outstanding families of jazz. “All of us learned how to play from my grandfather,” he told William Russell. “My dad [Willie E. Humphrey] played, my granddaddy [James Humphrey] taught a lot of musicians.” He started out on violin, then tried piano, before settling on clarinets and saxophones. They lived on Freret Street, between Napoleon Avenue and Jena Street, in a neighborhood filled with musicians.

As a young man, Willie J. Humphrey led a 22-piece orchestra at New Orleans University, where his grandfather taught on Saturdays. His first paying gig was in a band with his father. He worked in a band led by George McCullum and then, about 1919, the Silver Leaf Orchestra, which got work on the Streckfus riverboat the Sydney.

After that job and a few months in Chicago, he returned to New Orleans, working for a while as leader of the Frankie Duson dance band at the Pythian Roof Garden in the summer and the Royal Gardens in the winter. He also had a regular Saturday night gig at the New Orleans country club and fronted the Durand-Humphrey band, and then joined Kid Rena’s band for about a year.

About 1925, he returned to riverboat work, this time on the Capital, led first by Dewey Jackson and then Fate Marable. He lived in St. Louis, where the Streckfus Steamer line was based, for a few years in the mid-to-late 1920s. He recorded 4 sides for Vocalion in 1926 with the St. Louis-based Dewey Jackson’s Peacock Orchestra, including “Go On to Town” and “The Capital Blues.”

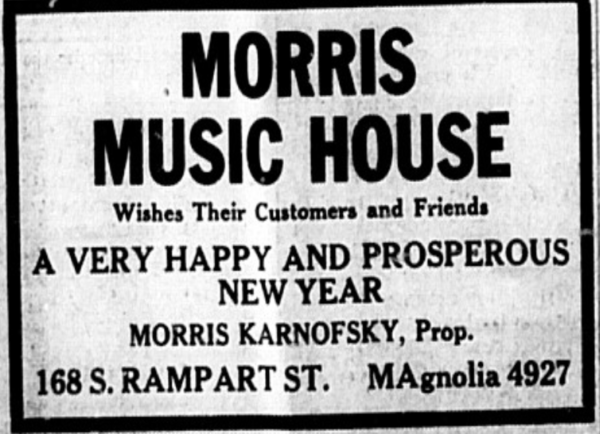

He returned early in the Depression to New Orleans where he had a growing family. “Things was bad then,” he said. “I had a few dollars, but a few dollars wouldn’t last.” With help from his father and Prof. Pinchback Tureaud, he got work teaching: “I taught at the schools before they put music in the Negro Schools. I got permission through [Morris] Karnofsky–he had a music place, he set up a school. I got 25 cents, 15 cents a student. I went house-to-house in a raggedy old Ford, sometimes 50 cents a lesson. I had to do the collecting: the school got some of it, too, I didn’t get it all. He [Karnofsky] had some used instruments, too, at a certain price, and I’d collect a dollar on that and get 15 cents of it.” [The Karnofskys hired 7-year-old Louis Armstrong to help with their coal deliveries, and Morris Karnofsky fronted him the money with which he purchased his first cornet; the brothers’ tailor shop was located at 427 S. Rampart St. Morris later operated Morris Music at 168 S. Rampart Street.]

Louisiana Weekly 1937

This teaching work may have extended into his service with what came to be known as the WPA band, which paid musicians to teach as well as to perform in concerts. After the war, he taught at the Grunewald School of Music. One of his pupils, the drummer Earl Palmer, said Bob Barbarin was his first teacher, but “Willie Humphrey was my best teacher. He took special pains with me and taught me all about my favorite subject, harmony. Willie always said he was surprised I’d come to Grunewald when I already played so good and knew all the New Orleans styles. He had known me as a kid, and I think he was proud that here I was, a dancer and a musician that wanted to formally learn what I’d been doing. Willie was a nice man.”

Humphrey’s teaching legacy has continued well into the 21st century. Charlie Gabriel, 90, a 4th generation New Orleans musician profiled in August 2022 in the Times-Picayune, named Humphrey in a list of legends who ‘tutored” him that included Kid Rena, Papa Celestin, Kid Sheik, and Willie’s brother Percy Humphrey. They “encouraged me to practice more so I would be qualified to play with these with these guys. I came up in the right time (1932-46), in the right place (on N. Galvez in the 6th ward). I was truly blessed to have all them tutor me. They helped me become who I am.” Soon after the war, Gabriel moved to Detroit with his family, where, still a teenager, he joined the Lionel Hampton band. He returned back to New Orleans in 2009 and performs regularly with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band,

Humphrey played in the Excelsior Brass Band with fellow Navy bandsman Bill Matthews, and the Eureka and Young Tuxedo Brass Bands.

He also told Russell that for years if there were any Black musicians playing in Carnival parades, it was because they were passing. “My grandaddy’s band, the Excelsior, they used to play in the parades, they needed them [back then], they didn’t have enough White musicians, but afterwards, they didn’t use them–I never seen no Negro bands in the parades when I was growing up. Then the first one we played, the Eureka, we played, to my memory, that was the first one.”

E.E. Bridges notes in March 1945 that Humphrey, Mus2c, “has had charge of directing the military band during rehearsals and during noon concerts. He isolates himself in a corner before each concert where he hums the various parts over to himself.”

Willie Humphrey 3rd from left with Jackson’s Peacock Orchestra. Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University

Thomas Jackson, saxophone, New Orleans.

Robert C. “Bobby” Johnson, piano, Rayne, Louisiana.

In May 1944, E.E. Bridges notes Johnson’s promotion to Mus2c and that he “plays nearly every instrument in the band, including piano.” In August 1944, Bridges reports that Johnson was singled out for having a “perfect shoe shine,” and in January 1945 he is cited as best ping pong player, inviting all opponents to try him out.

Eli Johnson

Earl Joseph, New Orleans.

Clyde Kerr, Sr., trumpet, arranger, New Orleans.

Born December 2, 1913 in Giddings, Texas, Kerr was the second child of Lilly Daisy Heck Kerr and Edward Joseph Kerr, who were both music educators. They would later add three more children to their family, and all would play musical instruments. Al Kennedy writes that Kerr’s father directed the Prairie View College Band and also high school bands in San Antonio and Dallas. His great-grandfather was a circus musician and his grandfather a musician and teacher. At Athens, Texas, Clyde Kerr’s parents were the entire faculty at the colored school; his dad organized a 30-piece community band there.

The family moved to New Orleans in 1919, where Clyde Kerr attended Daniel Elementary School for Colored and their home was quickly integrated into the Bourbon Street Black community. After transferring to McDonough 35 for high school in 1927 , he became active in the flourishing jazz scene. His primary instructor was Osceola Blanchet, who taught chemistry at McDonough and also performed with the Manuel Perez Jazz Band as well as the Osceola Five.

Kerr intended a pre-med major at Xavier College in New Orleans but soon began playing with bands led by Papa Celestin, Fats Pichon and others, including Sidney Desvigne’s Orchestra on the steamer President, and he also formed his own orchestra. In January 1937, Eddie Burbridge, on his “jive tour of clubs,” noted that “Clyde Kerr is really coming along with his Sharps and Flats” at the Tick Tock Tavern.

He graduated from Xavier in 1935 and was accepted at Meharry Medical College in Nashville. Instead of medical school, though, he enrolled in a teacher-training program and married “the love of his life, Violet Carmen Baquet.”

He wasn’t long into his first teaching job, at Bunkie, Louisiana, before enlisting in the Navy. He was still leading the Clyde Kerr Orchestra, and McNeal Breaux remembered a Navy recruiter visiting one of the band’s performances to recruit them, assuring them that if they enlisted they would “complete their military service while playing music in New Orleans.”

After the war, Kerr continued to play in bands around New Orleans but he built his lasting legacy as a teacher, first at Booker T. Washington High School and then Xavier Preparatory High School and Priestly Junior High School, where he retired in June 1976. Among his many successful students are Anthony “Tuba Fats” Lacen, James Rivers, and Michael Pierce. Al Kennedy’s excellent book, Chord Changes on the Chalkboard, is meticulously researched and fills in much more on Kerr’s early life as well as on several other influential early music teachers in New Orleans.

Walter Knight, chief, Passaic, NJ

Knight was the Lakefront Navy band’s White bandmaster.

Carey Lavigne, Jr. Shreveport, La., saxophone, clarinet

Carey Lavigne’s father was a druggist in Shreveport. The family moved to New Orleans when Carey was young, and his first music lessons, short-lived, were on piano. His “interests and efforts” turned to saxophones and clarinet, which he played for the Lakefront band.. He was 29 and a senior at Xavier University working towards a pre-med degree when he enlisted with his brother, Michael. At Camp Robert Smalls, he graduated “as honor man of his group” for which served as clerk. He composed “Lovers of Liberty” at Camp Smalls and continued to write, arrange, and compose while at Lakefront. He also played and arranged for several Xavier U. ensembles as well as the local bands led by A.J. Piron and Leary’s Orchestra. E.E. Bridges wrote that he was a top pool player. Lavigne’s compositions were performed regularly on the radio show “Skyway to Victory,” which aired on WWL on Thursday nights at 9:45 p.m. Two of his most popular: “Boot Camp Jive” and “Sailor.” When he was profiled in the Louisiana Weekly soon after arriving at Lakefront, he had recently completed his first classical composition, “Realm of Dreams.” He also wrote the band’s theme song.

Michael Lavigne, Shreveport, LA

Lavigne was also known as an excellent swimmer, according to E.E. Bridges.

1950 postcard of Bill Matthews, courtesy of the New Orleans Jazz Club Collection of the Louisiana State Museum

William Matthews, drums, trombone, New Orleans.

Bill Matthews grew up at 719 Newton Street, and his Algiers neighborhood was another that was permeated with music and support for the people who made it; his brother “Bebe” also played drums. Matthews started out on snare drums, calling himself “one of New Orleans’ original drummers.” From about 1915-19, he played with Buddy Petit’s band, with Kid Rena and Frankie Duson, and then John Robichaux’s playing at West End at Ponchartrain, and then with Duson’s orchestra. He remembers teaching drums to Zutty Singleton (another Navy man, though it’s unlikely in World War I that he would have played in a Navy band), who got his start playing at the Rosebud Theater in 1915.

On Alphonse Picou’s recommendation that he pick up something “easier to lug around, ” Matthews changed to trombone and began taking lessons from Vic Gaspard, “one of the great baritone and trombone players” in New Orleans. Originally from Algiers, by 1918 Gaspard was living at 1725 N. Robertson Street. Matthews’ first trombone was custom-built: Harrison Barnes, who lived across the street, gave him one with a good bell on it, and from Jack Carey’s barbershop, he got another with a good slide on it and put them together. Within about two weeks, Gaspard told him he had progressed enough to leave his lessons book at home; they subsequently went over some of Robichaux’s orchestral arrangements and Gaspard told him he didn’t need any more lessons: “You know more music than I do. I wish I had ever learned as much as you do.”

Growing up, he recalled hearing Buddy Bolden often at Mason’s Hall on Perdido Street; his recollections of “those days,” the music scene prior to the first World War, include jobs with Moret’s band at City Park and Audubon Park every season “with Dave Perkins and all them,” back when “white and colored musicians worked together.”

Matthews started his own band about 1922. During the ’20s, he also played briefly with King Oliver’s band, and then with Papa Celestin’s orchestra. He worked with the Excelsior Brass Band on both trombone and snare.

He toured with Jelly Roll Morton, which may have gotten him to Kansas City, and was playing in St. Louis with Charlie Creath at Jazzland, until he received a telegram asking that he and Pops Foster (who was playing on a Streckfus-steamer in St. Louis), join Sidney Desvigne’s band in Cincinnati playing on the Island Queen. Back in New Orleans, he joined Papa Celestin’s band performing on the pleasure boat The Greater New Orleans, for about five years.

Why he listed Port Arthur, Texas, as his home when he enlisted in the Navy is not clear.

After World War II, he worked regularly in Bourbon Street clubs, first with Papa Celestin’s Tuxedo Orchestra, and then for many years at the Paddock Lounge, where, eventually, Celestin became the house band leader.

He performed on several recordings, with his own band and also with Papa Celestin’s, which also included such notable New Orleans musicians as Slow Drag Pavageau, George Lewis, Alvin Alcorn, and Alton Purnell.

Bill Matthews died in New Orleans June 3, 1964.

Eddie Pierson. Courtesy of Historic New Orleans Collection.

Eddie Pierson, trombone, New Orleans

Eddie Pierson was born Aug. 1, 1904 in Algiers, La., and died in New Orleans on December 17, 1958. He played with Sidney Desvigne’s orchestra on riverboats in the 1930s, along with two other Lakefront bandsmen, Theodore Purnell and Louis Barbarin. He also worked with the Sunny South, A.J. Piron, and with the Barbarin and Young Tuxedo orchestras. He played on the steamer President in 1939 with Oscar Rouzan. From 1951, he played with Celestin’s orchestra and led that band after Celestin’s death in 1954.

Ted Purnell at Port Chicago en route to his St. Mary’s College posting. Courtesy of Hogan Jazz Archive, Tulane University

Theodore Purnell, alto sax & clarinet, New Orleans

Ted Purnell was born in New Orleans about 1903 and died there on November 25, 2974. He recalled studying clarinet for two years with Prof. William Nickerson before he was allowed to play a tune. He later took lessons from Adolphe Alexander, Sr. He was with David Jones at the Lavida Ballroom in 1925 and played on the Jones-Collins Astoria Hot Eight recording session in 1929. He joined the Sidney Desvigne band about 1930 in Peoria, Illinois, performing on the steamer Capital and then others during the 1930s before playing with Walter Pichon’s band touring with Mamie Smith in vaudeville.

He recalled recording with the Lakefront band and Leo Dejan and said it was “one of the best” he ever played with. He also said he preferred playing third saxophone to first because third sax “got off” more–that is, got to improvise and play more jazz. McNeal Breaux identified him as “Wiggles.”

“Or Mr. Wiggles,” Harold Dejan said, adding that he got the nickname from Sidney Desvigne’s bass player because “he couldn’t sit still.”

When the Lakefront band was broken up, Purnell and Carey Lavigne were sent to the St. Mary’s College Pre-Flight School band. Led by Marshal Royal, it was, Purnell said, the “best” he ever played with.

He was the pianist Alton Purnell‘s brother.

Lawrence Story

James V. Ursin, Jr., French horn, New Orleans

Like Leo Dejan, Ursin was a graduate of Xavier College.

John T. Welch, trumpet and baritone, Birmingham.

Welch was trained at Camp Robert Smalls and then assigned to the San Diego Navy Field Band and later transferred to NAS New Orleans at Lakefront. He was discharged on April 16, 1946.

• • •

Sources

Abbott, Lynn. “Dewey Jackson and His Peacock Orchestra.” Jazz Archivist 23 (2013): 35-37.

Albright, Alex. The Forgotten First: B-1 and the Integration of the Modern Navy. Fountain, NC: R.A. Fountain, 2013.

Barbarin, Louis. Interview with Richard B. Allen, William Russell, Ralph Collins. New Orleans. 22 June 1960. New Orleans, Hogan Jazz Archive, Tulane University.

—. Interview with William Russell, Richard B. Allen, and Bob Campbell. New Orleans. 27 Mar. 1957. New Orleans, Historic New Orleans Collection.

Breaux, McNeal. Interview with Al Kennedy. New Orleans. 2 Mar. 1994. Collection of the interviewer.

—. Interview with Barry Martyn. New Orleans. 2005. New Orleans: Hogan Jazz Archive, Tulane University.

—. Interview with William Russell and Richard Allen. 24 Nov. 1958. New Orleans: Hogan Jazz Archive, Tulane University.

Bridges, E.E. “Coloredata.” Bayou Tale Spinner. New Orleans, n.d.: 9. Collection of Al Kennedy.

—. “Coloredata.” Bayou Tale Spinner. New Orleans, 22 April 1944; 6 May 1944: 11; 20 May 1944: 9; 4 Aug. 1944: 14; 26 Aug. 1944: 14.

—. “U.S. Navy Band Musician Makes Hit as Composer.” Louisiana Weekly 28 Aug 1943: 6.

Buerkle, Jack V. and Danny Barker. Bourbon Street Black: The New Orleans Black Jazzman. New York: Oxford UP, 1973.

Burbridge, Eddie. “New Orleans after Dark.” Chicago Defender 23 Jan. 1937: 5.

Chase, Dooky. Interview by Jack Stewart and Tad Jones. 29 Sept. 1999. New Orleans: Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

—. Personal interview with author. New Orleans: 10 Oct. 2014.

Clark, Nell. “Ida Leveled The Karnofsky Shop, Louis Armstrong’s Second Home.” NPR. 31 Aug. 2021. npr.org. 19 Aug. 2022.

Coletta, Paolo E. “New Orleans, LA., Naval Reserve Aviation Base, 1941-1943, Naval Air Station, 1943 -.” in United States Navy and Marine Bases, Domestic, Paolo E. Coletta, ed. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1985: 333-336.

Dance, Stanley. “Jazz Musicians in San Diego.” 10.1 (Spring 1899) Black Music Research Bulletin. Chicago: Columbia College: 10-11.

Dejan, Harold. Interview with William Russell. 3 Feb. 1961. New Orleans: Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

Desvigne, Sidney. Interview with William Russell. 18 Aug. 1958. New Orleans: Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

Determeyer, Eddy. “When Dooky Fooled Dizzy,” in Big Easy Big Bands: Dawn and Rise of the Jazz Orchestra. Groningen, Netherlands: Rhythm Business, 2012: 201-212.

Eugene, Wendell. Interview with Barry Martyn. 4 Nov. 1999. New Orleans: Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

Gormin, Ken. “The Spotlight.” Item. 6 Aug. 1942. 13 [?]

Goss. “Crescent City News.” Chicago Defender 8 Jan. 1944: 15.

“Hot Trumpeter Now Blowing for U.S. Navy Band.” Louisiana Weekly. 25 Sept. 1943: 6.

Hughes, Langston. The Big Sea: An Autobiography. 1940. New York: Hill and Wang, 1986.

Humphrey, Willie J. Interview by William Russell. 15 Mar. 1959. New Orleans: Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

“John T. Welch.” in A Little Known Legacy: The Great Lakes Experience: A Salute to African-American Navy Bandsmen at the Great Lakes Naval Base 1942-45 [Chicago, IL] [Feb. 2003]: 24. Collection of Carl Foster.

Kennedy, Al. Chord Changes on the Chalkboard: How Public School Teachers Shaped Jazz and the Music of New Orleans. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow, 2002.

Martyn, Barry. Telephone interview with author. New Orleans: Oct. 12, 2014.

Matthews, William. Interview with Bill Russell New Orleans: 10 Mar. 1959. New Orleans: Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

Meadows, Eddie S. “African Americans and “Lites Out Jazz” in San Diego: Marketing, Impact, and Criticism: 244 – 276. in California Soul: Music of African-Americans in the West, Jacqueline Cogdell DjeDje and Eddie S. Meadows, eds. Berkeley: U of California P, 1998.

“Naval Air Station Lakefront, New Orleans, 1940s.” The Past Whispers. Old New Orleans. Web. 15 June 2014.

“Navy Band at Lake Pontchartrain Rated as One of the Best Musical Organizations in the Country.” Photo caption. Pittsburgh Courier Aug. 21, 1943: 12.

The Negro in Louisiana. Typed manuscript. Marcus Christian Collection, New Orleans: U of New Orleans.

Newhart, Sally. The Original Tuxedo Jazz Band. Mt. Pleasant, SC: History Press, 2013.

“Oscar Rouzan Is Top Alto Sax. Man with Desvigne,” Louisiana Weekly 17 Mar. 1945: 6.

Purnell, Theodore. Interview with William Russell. Feb. 3, 1961. New Orleans: Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane University.

“Robert Taylor, Veteran (Part 2)”. giraffe44. 22 Aug. 2012. RobertTaylorActor.blog. 20 Feb. 2023.

Rose, Al. I Remember Jazz: Six Decades Among the Great Jazzmen. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1987.

Rose, Al and Edmond Souchon. New Orleans Jazz: A Family Album, 3rd ed. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1984.

Scherman, Tony. Backbeat: Earl Palmer’s Story. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Inst. P, 1999.

Spera, Keith. “Living in the Moment.” New Orleans Times-Picayune 28 Aug. 2022: E1, 7-10.

“Station Band Beats out Marches, Boogie-Woogie.” New Orleans Item 28 Sept. 1942: 31.

Stolp-Smith, Michael. “Port Chicago Mutiny (1944).” BlackPast.org. Web. 4 Mar. 2015.

“39 Louisianans Begin Training at Camp Robert Smalls.” Louisiana Weekly 29 Aug. 1942: 7.

“23 Musicians Inducted for Naval Band.” Louisiana Weekly 15 Aug. 1942: 6.

Wilkinson, Chris. Jazz on the Road: Don Albert’s Musical Life. Berkeley: U of California P, 2001.

Woods, David L. “New Orleans, La., Naval Station, 1803-1818; Algiers Naval Station, 1901-1933, 1939-1947; Naval Station, 1947-1966; Naval Support Activity, 1966-1983.” in United States Navy and Marine Bases, Domestic, Paolo E. Coletta, ed. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1985: 333-336.

“Zutty Singleton.” Top 500 Drummers. Drummerworld.com. 17 Feb. 2023.

–November 10, 2024