Treasure Island is the big white hexagon extending out from Yerba Buena Island in the middle of the SF-Oakland Bay bridge. Treasure Island vintage postcard collection.

That Treasure Island was to get one of the first Black Navy bands of World War II was announced in mid-August 1942. They were one of several bands recruited as a unit from the ranks of popular jazz musicians, duty in a Navy band being much preferable to the high odds of being drafted by the Army and into who knows what role and where?

Barracks construction at Treasure Island. Treasure Island Museum.

The first Black band destined for Treasure Island was organized after Secretary of Navy Frank Knox announced on June 14, 1942 that Blacks would no longer be restricted to service ranks, primarily cooks and stevedores, but before Camp Robert Smalls was ready to house them. Recruited from Chicago, many of the Treasure Island bandsmen were professionals who were living in Chcago, and others had been musically active in the area, which made it possible for their first “barracks” to be locally found housing. Until Camp Smalls was ready to house them, they rehearsed in the Savoy Ballroom every afternoon. They had entered the profession came from diverse backgrounds, musically and geographically, from Los Angeles, Minneapolis, New York, Alabama, Pittsburgh, and New Orleans as well as Chicago. Collectively, their musical pedigrees were impressive, its members having played with Fats Waller, Fletcher Henderson, Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Chick Webb, King Kolax, Coleman Hawkins, Duke Ellington, and Blanche Calloway among many other bands, and several symphonies and orchestras.

Savoy Ballroom, Chicago, post card detail

The T.I. bandsmen started at $66 a month with a daily living allowance added in; most were rated Musician 2nd or 3rd class. They were promised their service would be at the new base in San Francisco Bay and that they would stay together there for the duration of the war. After training and a long train ride, they arrived at Treasure Island on October 27, the first Blacks on a base previously comprised of 2,500 White men.

African-Americans & the Navy

The Navy was infamously slow to integrate, insisting that no White sailor would take orders from a Black, a circumstance that might not be avoided aboard a ship in war. So the Navy integrated its rating systems before integrating its ranks, meaning that prior to 1942, Blacks were restricted to service ratings of cook and steward, out of which no promotion into petty officer was possible: if you entered as a Cook, you left as a Cook. Black Navy bandsmen, with musicians ratings, were the first in the modern Navy who could move up that ratings rank, though to a certain point–a glass ceiling, really: they were kept from making the leap from Musician 1c to Bandmaster, which remained an exclusively White rating throughout the war. And the ranks themselves remained segregated; Black bandsmen served with other Blacks. It’s not surprising that the Black press thought creating Black bands hardly a progressive move, sometimes referring to the bands as Jim Crow units that furthered common stereotypes. Black Navy jazz bands integrated many spaces, though within those spaces they were rarely able to step out from a kind of third wall that separated them from their audiences.

Black bandsmen were also barred from attending the Navy School of Music, a requisite for all White musicians wanting to serve in Navy bands. This necessitated the recruitment of men who could already play, the Navy theorizing that they could be taught to march more easily than to play music at a professional level. Camp Robert Smalls was one of three bases built within the complex known as the Great Lakes in Chicago to house Black sailors. Its Barracks 1812 became informally known as the Black School of Music, its dlrector, Len Bowden. A Commander Peabody ran the future T.I. bandsmen through “strenuous rehearsals, drills and intricate band formations.”

Musicologist Samuel Floyd, who founded the Center for Black Music Research in Chicago and wrote the first history of the Navy’s Black bands, has called the training at Camp Smalls “the greatest single educational and musical experience for Blacks ever to occur in America.” Von Freeman, the Chicago jazzman who also played with the Navy’s Hellcats in Hawaii, said: “All of the great musicians ended up at Great Lakes. It was an incubator for the best and the brightest lights in the jazz world at that time, and the musical jam sessions were simply phenomenal.”

But not until the “Golden 13” were commissioned as officers in March 1944 did the Navy move forward in a significant way towards integrating its ranks.

Treasure Island & San Francisco Bay

Officially labeled the U.S. Naval Training and Distribution Center, San Francisco, the 403-acre station popularly known as Treasure Island was created on the shoals of Yerba Buena Island on what had recently been constructed for the 1939 Golden Gate International Exhibition. A mile long and nearly .75 mile wide, it dwarfed Yerba Buena.

On February 28, 1941 its space and all its structures were leased to the Navy. While the base was being prepared, its first barracks and classrooms for all personnel was the Delta Queen--during the war, the USS Delta Queen–the steamboat built in 1924 and known primarily for its many years service on the Mississippi River. In addition to new construction, the Navy re-purposed some of the fair’s structures, creating barracks in the Hall of Western States and in the Federal Building a galley that would eventually serve food to over 7,000 men an hour, seating up to 3,000 at a time. The Billy Rose Aquacade was converted to one of three swimming pools, and two buildings became theaters–before war’s end, a third was built.

On February 28, 1941 its space and all its structures were leased to the Navy. While the base was being prepared, its first barracks and classrooms for all personnel was the Delta Queen--during the war, the USS Delta Queen–the steamboat built in 1924 and known primarily for its many years service on the Mississippi River. In addition to new construction, the Navy re-purposed some of the fair’s structures, creating barracks in the Hall of Western States and in the Federal Building a galley that would eventually serve food to over 7,000 men an hour, seating up to 3,000 at a time. The Billy Rose Aquacade was converted to one of three swimming pools, and two buildings became theaters–before war’s end, a third was built.

Treasure Island was the primary Navy installation in San Francisco, a last gateway for service into the Pacific and a first port for those returning stateside from that service. T.I.’s embarkation center processed an average of 20-25,000 men a month. All Marines entering area service stopped by T.I first for processing. During the war, over 4.5 million service personnel would find at least a transitional stop there. The Navy also operated an armed guard center and an advanced Naval training school (ANTS) for mining and radio electronics specialists. Its auxiliary airport and crews supported helicopters, fixed wing planes, seaplanes, blimps, dirigibles and airships, repairing and preparing them for return to service. Its first 18 WAVEs arrived in November 1942; by war’s end, over 800 were stationed there. T.I. WAVES were among over 200 from five bases who paraded in Oakland to celebrate their first anniversary in July 1943, the T.I. band leading the parade.

Red dots – mine fields. Red hash-marks – a submarine net. Green squares – gun installations. Black squares – troop quarters. Green squares – mine & submarine defenses. Detail of larger map. National Park Services.

Treasure Island’s establishment was a major step towards turning San Francisco into “one big Navy base.” Its command reach extended to Camp Parks, a pilot training base at Livermore, and Fleet City, which included Camp Shoemaker and the Port Chicago Naval Magazine, at Concord, 45 miles inland. The Navy also had two shipyards, one at Hunters Point and another at Mare Island, the only place on the West Coast where submarines were built; its Tibron Net Depot, which created over 100,000 tons of netting for West coast ports, created the 7-mile long net that protected the bay; only 85% complete on December 7, 1941, overtime work finished it by December 23.

The Army had long been tasked with protecting San Francisco Bay, with Forts Baker, Barry, and Cronkhite around the tip of Marin County. Fort Point was built prior to the Civil War to protect the Golden Gate Straits. Within the bay, Fort Mason was the principal Pacific port of embarkation for soldiers–about 1.7 million were processed there; the Presidio and Forts Scott and Miley and Hamilton Army Airfield were major installations. Alcatraz was a military prison.

Shipbuilding dominated San Francisco’s war economy: Kaiser’s Richmond Shipyard Number Three built 1,400 vessels–a ship a day, on average; Mare Island Naval Shipyard provided repair and shipbuilding facilities; and the Union Iron Works Shipyard south of the Embarcadero built cruisers, early S-class submarines, and battleships. They and over 30 private shipyards in the area built and launched an additional 1,600 ships during the war

Entertaining the hundreds of thousands of troops and support personnel who came through San Francisco was also a major part of that war economy. The combination of performers who’d have played such a market anyway combined with the many USO shows and countless troops headed to the Pacific Theatre, all spending considerable time at leisure in the city as they awaited transport, created what often seemed like an endless party scene, with always a need for a good band.

Courtesy of Steefenie Weeks

Jim Crow West-coast Style, Troubles in the Bay

Prior to and early in the war, many Black leaders and its press were calling for Blacks to refuse a fight against the evil isms of the world–Naziism and fascism especially–until the U.S. had conquered racism at home, a campaign soon ended in favor of a more dominant ism, patriotism, as the war ramped up. Only small steps such as the integrating of the Navy’s ranks with musicians ensued, a move early on decried by some as just another version of Jim Crow.

San Francisco’s racial dynamics were transformed during the early days of the war by imported racism; that is, the large influx of White Southern workers brought with them attitudes that infected many places where American troops served, most especially Hawai’i. Two incidents arose from the tensions brought about by the emergence of Jim Crow practices in the Bay area, both at or near Navy bases with large numbers of Black personnel. The first, at Vallejo, which like much of the area enjoyed a war time boom in its population and economy, erupted in late December 1942. The initial round of violence ignited on “a rowdy stretch” of Georgia Street, outside a nightclub and near one of two USOs in the Bay area that openly welcomed Blacks. The Navy and local police blamed the outbreak on those Southern workers and their unfortunate attitudes to Vallejo and Mare Island–where Black sailors were bossed by White civilians who frequently directed them with overtly racist language–and the over-reaction of those Black sailors at this treatment on base and in town.

Whether a riot or an uprising, something went badly wrong on December 27, and Marines were called to quell a disturbance that Javier Arbana terms “a rebellion against the segregationist policies of the Twelfth Naval District and the Navy’s open tolerance of Jim Crow in the quotidian spaces for nightlife.” A combination of Marines and local police spent a couple of days quelling the disturbance created by 200-400 Black sailors who would not disperse that night. How many were shot by Marines (or police) is not known. These events resulted in a call by the NAACP “for the reform of the Twelfth Naval District,” which was already known for its lax attitude towards the prevalence of Jim Crow-like conditions throughout its jurisdiction. But the District command, headquartered at Mare Island until near the end of the war, seemed oblivious to what was going on literally outside its doors as well as in the larger contexts regarding racial conditions in its ranks and how they were evolving. The district’s 4-volume history is housed at the Navy Department Library at the Washington, D.C. Navy Yard, and in recent years the Navy has made good much of what has previously been kept secret more readily available.

Frank Rowe’s woodcut commemorating the Vallejo uprising, December 1942. Courtesy of Nancy Rowe & Javier Urbana, whose caption for it reads: “Scene of U.S. Marines shooting unarmed Black sailors in downtown Vallejo, California during World War II, based on Robert Pearson’s 1964 book No Share of Glory.”

One of the most notorious events of the war, the explosions at Port Chicago and subsequent trial for mutiny, outraged Black leaders and press. Racial and labor troubles prior to the 1944 “mutiny” had precipitated an unknown number of strikes and labor stoppages at both bases. Like at nearby Mare Island, Port Chicago’s worst jobs were held by Black stevedores tasked with unloading large crates of ammunition from rail cars and onto ships, sometimes in triple shifts, and often with a civilian boss wielding racist language with impunity.

The Navy’s official explanation of what led to the troubles at Port Chicago, where over 5,000 tons of munitions exploded:

In addition to the naval service’s segregation policy, the relative geographic isolation of the base, triple-shift operations, often-hazardous working conditions, lack of recreational facilities, and the unending tedium of the duty rotation contributed to discontent, low morale, and disciplinary issues. The chain of command focused primarily on maintaining a high operations tempo with periodically increased loading quotas.

The official contemporary summary of the events is awful, dramatic and detailed:

On the evening of 17 July 1944, disaster struck. Two cargo ships, SS Quinault Victory and SS E. A. Bryan, were berthed at the munitions pier, the latter vessel being loaded with a variety of munitions. In the holds of E. A. Bryan or on the pier ready to be loaded were 4,606 tons of antiaircraft ammunition, aerial bombs, high explosives, and smokeless powder. Another 429 tons were still in 16 railcars on the pier, awaiting transfer to both ships. According to witness statements, at 2218 (10:18 PM) a dull clang (possibly caused by a falling cargo boom) and a sound of splintering wood preceded a blinding flash and heavy detonation on the pier, followed within seconds by smaller detonations and then the massive explosion of munitions in E. A. Bryan’s holds. The ship, most of the pier, all structures within a 1,000-foot radius, and many of the flatcars disintegrated. The explosion blew Quinault Victory into large pieces that sank in the waters of Suisun Bay. A Coast Guard fire barge was blown away from the munitions pier and sank, taking its 5-man crew with it. The 320 individuals in the immediate proximity of the blasts— Navy personnel on the loading details, a Marine Corps sentry, the ships’ Navy Armed Guard and merchant mariner crews, and civilian employees—were killed instantly. Of these, the remains of only 51 were identifiable afterward. African American Sailors comprised nearly two thirds of those killed. More than 250 other personnel at the Port Chicago facility were injured, a number seriously. Most of the buildings on base, many of light frame construction, were damaged; the rest were destroyed. Secondary fires raged and munitions continued to cook off for some time after the explosion of E. A. Bryan. Smoke billowed over two miles into the sky, and the shock of the detonations caused structural damage and broke windows in surrounding communities, was felt 40 miles to the southwest in San Francisco, and registered as far away as Nevada. A number of privately owned vessels and small boats underway in Suisun Bay were damaged by falling debris.

After the explosions, a Navy inquiry found no one really to blame, except perhaps the Black stevedores who hadn’t been able to absorb all the necessary training, which might also have been a bit lax. After the Port Chicago survivors were transferred to Mare Island and ordered to work again, under similar circumstances, many of them refused. They were convicted of mutiny in an October trial at Treasure Island and then imprisoned for nearly two years, before being released and re-assigned to menial Navy tasks before their discharge. Not until 20245 were they pardoned, all posthumously, when the Navy agreed, finally, that those refusing to work “did the right thing.”

It’s difficult to imagine the impact of the Port Chicago story on Black servicemen, especially those in the Treasure Island band who’d surely have heard those explosions, though it would be some days before news would filter out, primarily via the Black press. The Port Chicago courts martials were held at Treasure Island, where the Black mutineers were first held. Whether the bandsmen knew of those imprisoned stevedores that shared their Treasure Island home, or had any interaction with them, can only be imagined. The Navy did a fair job, too, of keeping newspapers like the Chicago Defender off its bases, furthering the isolation the T.I. bandsmen must have felt.

Stevedores unloading ammo at Port Chicago. US Navy.

Port Chicago aftermath. US Navy.

Port Chicago aftermath. US Navy.

Survivors of the Port Chicago disaster peer from their barracks windows. US Navy.

Two civilian groups organized to assist troops helped maintain the status quo. The Red Cross famously “Jim-Crowed” its blood, not letting “Black” blood to be put into White bodies. The USO, its 3,000+ clubs adhering to “local standards,” was not much better. Generally, in USOs where Blacks were not kept out, they were made uncomfortable enough to not stay or return. San Francisco had six USO clubs for Whites, one for Blacks, at 1530 Buchanan Street. A USO proposed to welcome Blacks was kept from opening in Richmond after locals protested its location. How deeply did Jim Crow infest San Francisco? One Black bandsman recalled being refused service at the Stage Door Canteen while he was on break from performing there. It seems the norm that bandsmen in the South expected was also prevalent in San Francisco; that is, they would usually be playing in places and for events that they would not have been allowed to attend as patrons. As Thomas Gavin, the B-1 vet who also began the marching band at Fayetteville State University said, “We often played in places where we could not have danced to the music we were playing.”

Back to the Music: Treasure Island’s first Black Navy band a big hit at the Stage Door Canteen

The T.I. band worked regular Navy duties tailored to the particulars of its base, but its unique location contributed to its off-base duties, as the San Francisco area was dense with military personnel. The need, then, for good bands to entertain them was great. The San Francisco Chronicle daily listed over 40 “activities for servicemen” hosted at church and civic spaces and six USOs. Its columnist “The Owl” covered highlights of club performances and musical activities, all catering to White audiences.

The demand for good bands was steady, and playing for club dates and dances was what the T.I. bandsmen had been doing professionally prior to the war, it just happened that most of such work for them were Navy-sponsored. Whether they worked outside gigs is not known–the Navy frowned on the practice though it was not uncommon, especially for bandsmen serving at stations that did not allow Blacks to stay on base, as at St. Mary’s College, whose players worked San Francisco gigs as often as possible–many of them had been professional musicians in the city before the war and had homes in the area. Most of those professionals had been members of the White musicians union Local 6 subsidiary, which had taken over operations of a previously all-Black union in 1934, and their best work was in the Filmore district clubs.

The bandsmen kept to themselves and their work. The Masthead described their catalog and their routine:

They play at colors, programs at Pre-Embarkation, operational training school, noonday concerts or jam sessions at the Tower of the Sun’s bandstand. Then to one of the Island piers to play for bluejackets before they set sail for destinations unknown. Then back to barracks in time to make orders for more engagements.

Those on-base engagements were both formal, such as graduations, openings, and recognition ceremonies, usually with the full band, and recreational events, dances and smokers (boxing exhibitions) especially, usually with the swing band. Some are noted in The Masthead.

Two factors made Treasure Island’s one of the more remarkable of the Navy’s war bands: the talent level of those recruited for this band–as well as for those who would, in 1944, replace it; and its location in San Francisco Bay, where their performances in the city for war bond rallies and parades, war loan drives, Army-Navy shows, and commissioning ceremonies for ships launchings attracted large crowds. The Masthead names the USS O’Ryan, USS Ashland, and USS The Sullivans as “among the ships that have slid down the stocks as the band’s patriotic notes climaxed the fitting ceremonial tribute paid to those honored and courageous sons of liberty who gave their lives in order that democracy may hold high the torch of freedom that will lead this war-torn, war-wearied world to a world of peace and brotherhood.”

On base, they were especially popular with daily concerts of patriotic and popular tunes. But it was their swing band, cut from the larger 22-piece band, that got most of the attention. It was featured at “leading theatres in downtown San Francisco,” and it short-waved recordings overseas for the “doughboys who are delivering the goods that will eventually spell disaster for all the “isms” designed to conquer and enslave the world.”

The swing band quickly became a popular and regular attraction at the famous Stage Door Canteen, “the home of happy G.I. guys who ‘riff like mad’ to the torrid tunes and sizzling rhythms of this fine band.” After it opened, its base performances were so curtailed that the base organized a second dance band of volunteers to work dances and smokers, and then a second Navy band, that is, one comprised of bandsmen serving at Musician rank, arrived.

Robert E. Johnson–who, after the war would become a founding editor at Jet magazine–wrote in The Masthead that the band’s history “evidences a veritable note of true patriotism”:

Like Captain Glenn Miller and Artie Shaw, who, in the acme of their musical careers, dropped their batons to give their talent to “deal ol’ Unc’ Sam,” the members of the TREASURE ISLAND band being overwhelmed by a similar surge of patriotism, gave up their urban gayety and key positions in various renown musical aggregations and volunteered as a unit to “don the gobs” of this military organization—the U.S. Navy.

He added that “because of their spontaneous recognition, the band received top billing and was called upon to play concert and dance engagements in San Francisco and neighboring cities.”

On base, they most often played for segregated events, and as more Blacks were stationed there, sometimes with big USO shows staged for Black personnel at Treasure Island and other bases, including shows headlined by Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and the Nicholas Brothers.

In San Francisco, their regular performances at the legendary Stage Door Canteen, after it opened in April 1943, furthered their reach and reputation. Like its New York counterpart, the Stage Door quickly became a go-to spot for stars eager to network while showcasing their patriotism as well as their talents. Open daily at 430 Mason Street from 6 p.m. to midnight, it offered non-stop entertainment and continuous dancing as well as coffee, sandwiches, and cake, all for the benefit of troops at leisure, an average of 2,000 a day.

At the Stage Door, the T.I. swing band’s dance performances might be interrupted at any time by the sudden appearance with them on stage of a star, as the Stage Door hosted “most of Hollywood’s stage, screen and radio celebrities and many of the nation’s great dance bands.”

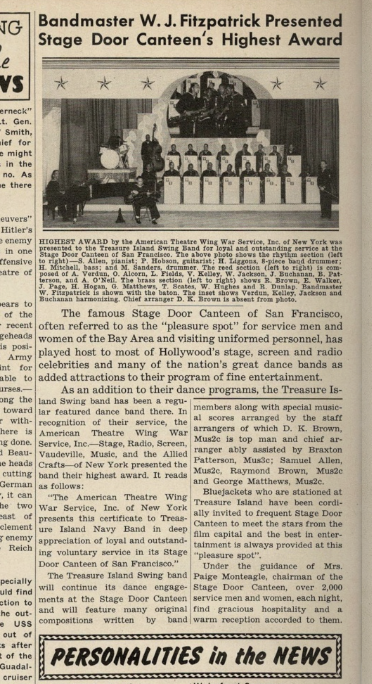

The band was honored by the Stage Door’s sponsors with “its highest honor,” a commendation that read: The American Theatre Wing War Service, Inc. of New York presents this certificate to Treasure Island Navy Band in deep appreciation of loyal and outstanding voluntary service in its Stage Door Canteen of San Francisco.

The band was honored by the Stage Door’s sponsors with “its highest honor,” a commendation that read: The American Theatre Wing War Service, Inc. of New York presents this certificate to Treasure Island Navy Band in deep appreciation of loyal and outstanding voluntary service in its Stage Door Canteen of San Francisco.

They also integrated several USO shows, preforming with Bing Crosby’s and Edward G. Robinson’s, they played the last set of a big bond rally headlined by Artie Shaw’s orchestra, and the full band was the sole feature of a concert at Stern Grove.

The full band rehearsed over 600 arrangements, including 350 popular dance arrangements, 175 concert pieces, 80 forceful marches, and scores of novelty tunes as well as an untold number of original numbers composed by bandsmen.

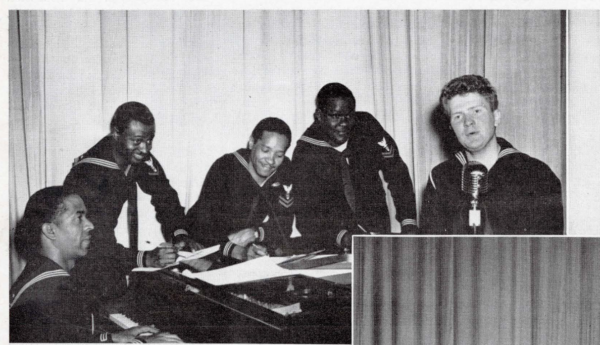

Among the stars of its 17-piece swing band were the principal arrangers, who also wrote original tunes for performance: David K. Brown, Mus3c, “top man and chief arranger ably assisted” by Braxton Patterson, Raymond Brown, George Matthews, and Samuel Allen, all Mus2c. Allen and Van Buren Kelly led the swing band. David Brown and Leonard Fields also took advantage of their proximity to the University of California, Berkeley, to enroll in music education classes.

The band’s first big engagement came in early December at a concert to celebrate the base’s newly organized Ship’s Service, the detail which would be charged with recreation services, and of scheduling the band’s performances. Artie Shaw and his orchestra opened the show; the T.I. swing band closed it.

They were part of the 2-show engagement that opened at a newly opened base theater the USO show “Keep Shufflin'” in early January. Produced by Noble Sissle and based on his WPA show, which had been adapted from the 1928 Miller & Lyles Broadway musical, it was touted as one the biggest of 15 USO stage musicals on tour in 1942. It included plenty of “jive and swing,” boasting “top Negro talent” in a cast of 38, with a 9-piece band led by Eubie Blake.

In April 1943, for the opening of a new gym and swimming pool, the band played the National Anthem and later entertained a Chiefs Party called “the best ever,” with over 150 Chiefs attending.

In May, for the radio show “Treasure Island on the Air,” they were part of the Hellzapoppin USO show, starring Lynn Bari and Allyn Joslyn, based on the wacky Three Stooges-like movie of the same name.

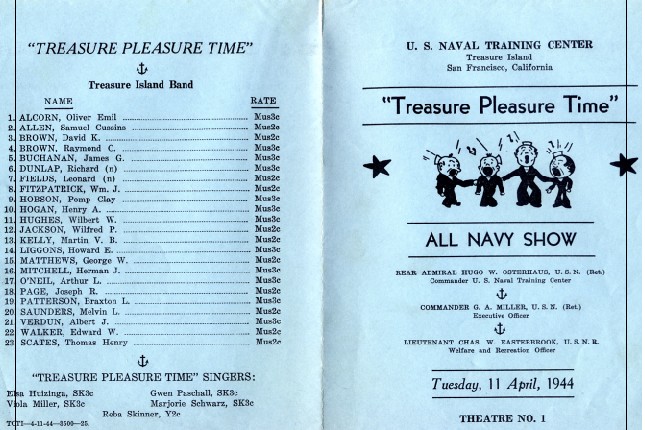

One of their biggest engagements was a July 3 concert they presented at Stern Grove in San Francisco, and during that summer the camp began producing its own variety shows, “Treasure Pleasure Time,” which starred the band and included singers and other acts drawn from base volunteers. Its January 1944 show featured over 100 performers, and in May the “hillbilly barn dancing” version included “jive, joy and wacky goings on,” with new music and lyrics written especially for this show by the swing band’s Raymond Brown, Braxton Patterson and Samuel Allen.

In September 1943 they were featured in “perhaps the greatest military spectacle ever before presented in San Francisco,” celebrating California’s statehood and launching the U.S.’s third War Loan Drive–northern California’s goal, $480,000. Over 12,000 marchers from all service branches were joined by Roy Rogers and Trigger Also, lots of military machinery: “imposing pieces of mechanized equipment” that afforded for locals an opportunity “to see for themselves the vast quantity and variety of fighting machinery needed for America’s still overwhelming battle against the forces of darkness,” including amphibious jeeps, 75 mm guns, assault guns, beach boats and “much other moving apparatus never seen here before.”

Courtesy of Steefenie Weeks.

In early 1944, the base began producing its own shows, “Treasure Pleasure Time,” that featured the band or the swing band and a variety of talent selected from base personnel. In April 1944, “future Paul Robeson” James Allen Jones sang “Ole Man River” and as an encore “The Lord’s Prayer.” The swing band’s Edward Walker “soothed the pulsating beats of throbbing hearts with his [trumpet] solo in Raymond Brown’s beautiful arrangement of Fats Waller’s song “Ain’t Misbehaving.”

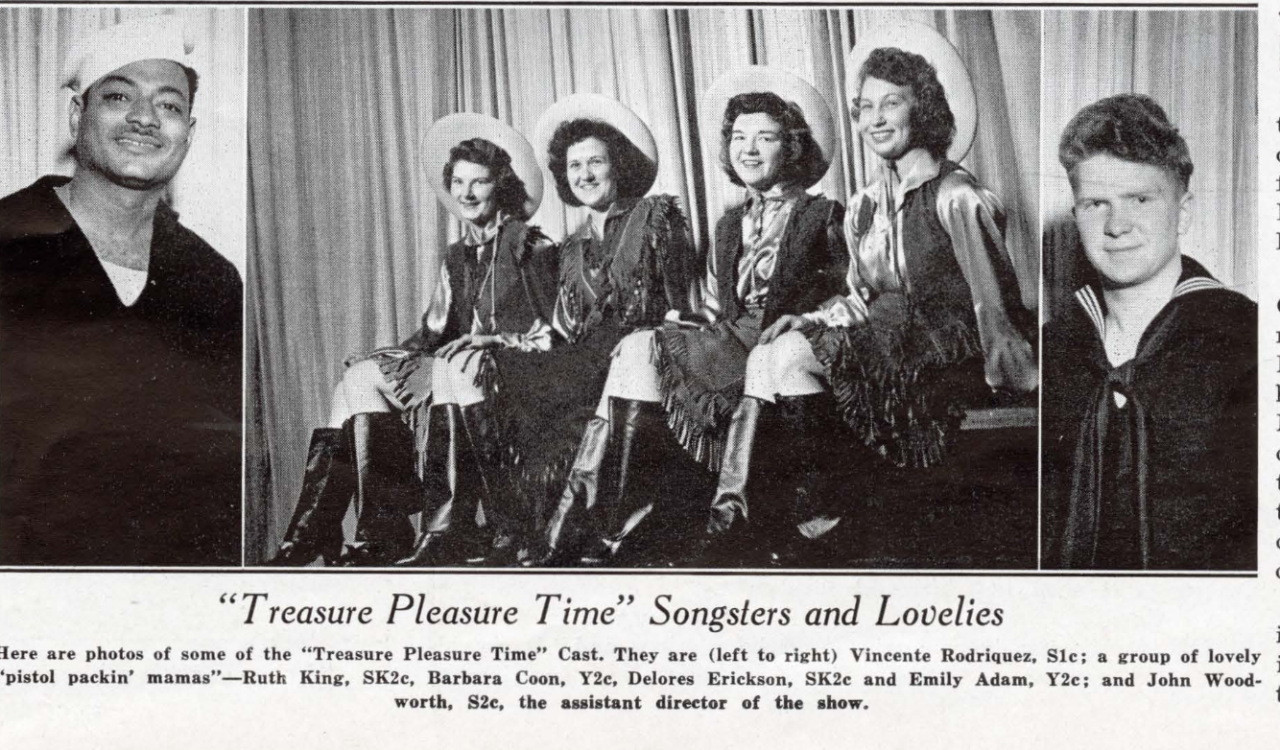

In a May production, the T.I. swing band provided “musical background” during another all-T.I. show with a WAVEs trio, an accordionist/comedian, an impersonator, several vocalists, a hillbilly quartet of White “jivesters,” a “square dance presented by a group of ‘pistol-packin’ mamas,'”and western movie star and champion yodeler Hal Careyy.

The Masthead. 13 May 1944: 1. Collection of the author.

Also in May, the full band played at the “I Am an American” program at the Civic Center in San Francisco with bands from area Army, Marines, and Coast Guard bases and entertainers Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, and Dina Shore, and a keynote address by Gov. Earl Warren.

In August 1944, it played for a gala dance hosted on Treasure Island for over 1000 WAVES, and the swing band backed up Bing Crosby in a preview of his upcoming USO show, with Joe de Rita, Darlene Garner, and the Baxter & Harris dancers.

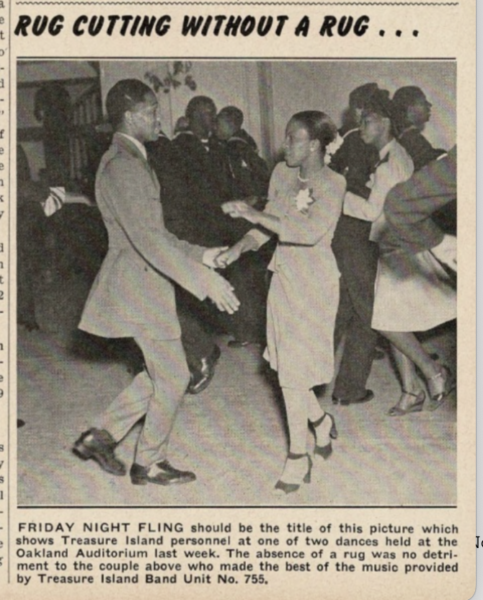

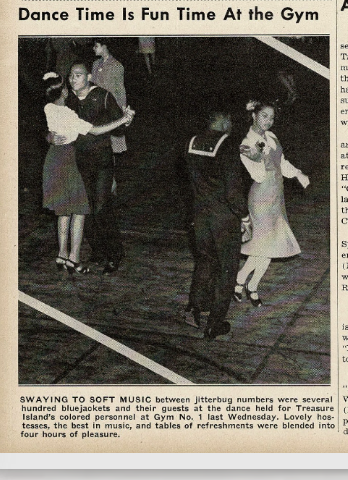

The number of Black personnel at Treasure Island had grown sufficiently that by August 1944, the band played its “initial dance for colored bluejackets,” the first of several, with USO girls from the Bay area hosting: “Fine music, girls and food will highlight the affair.”

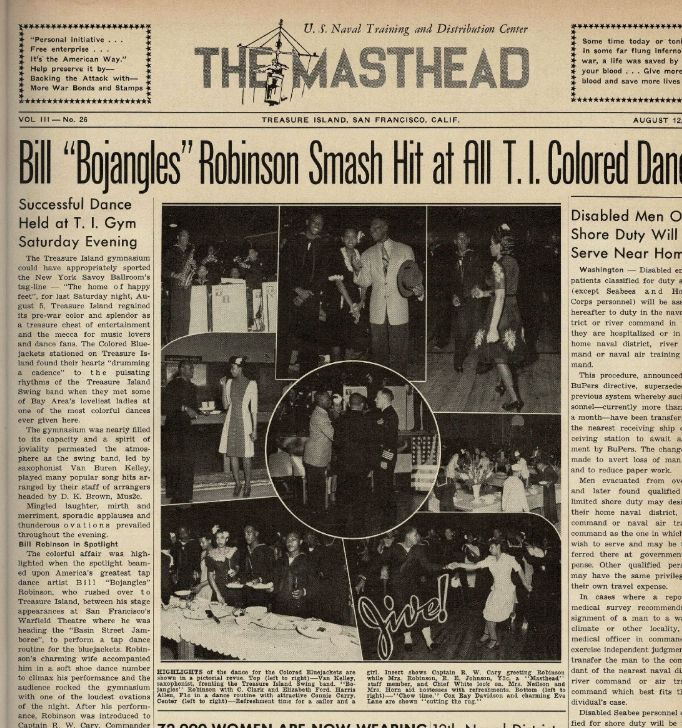

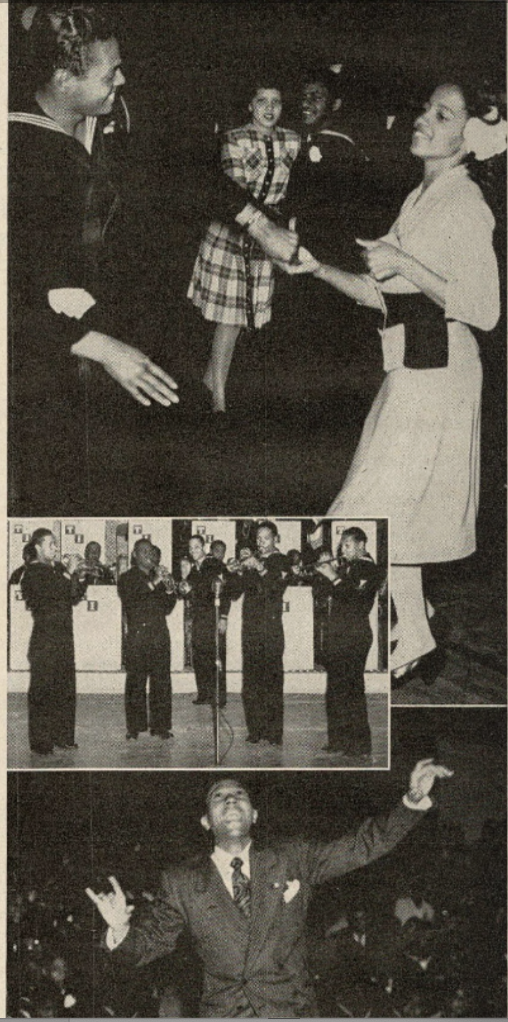

A week later, Bojangles Robinson was a “smash hit at the all T.I. colored dance.” Van Buren Kelley led the swing band, which played “many of their hits arranged by D.K. Brown,” to a nearly packed gym. Robinson, who was between performances in San Francisco, said that of all his shows for military audiences, he loved Treasure Island the best because it was the “cream of all the music affairs.”

One indicator of how good and professional and well-mannered the bandsmen were wherever they performed was their selection as entertainment for a WAVES picnic at La Honda–all White women. The all-day affair included lunch, a sermon, games, and a parade. Just a couple of weeks earlier, they’d performed at T.I.’s “first dance gala affair,” honoring over 1,000 WAVEs, from throughout the Bay area, that ran from 10 p.m. – midnight.

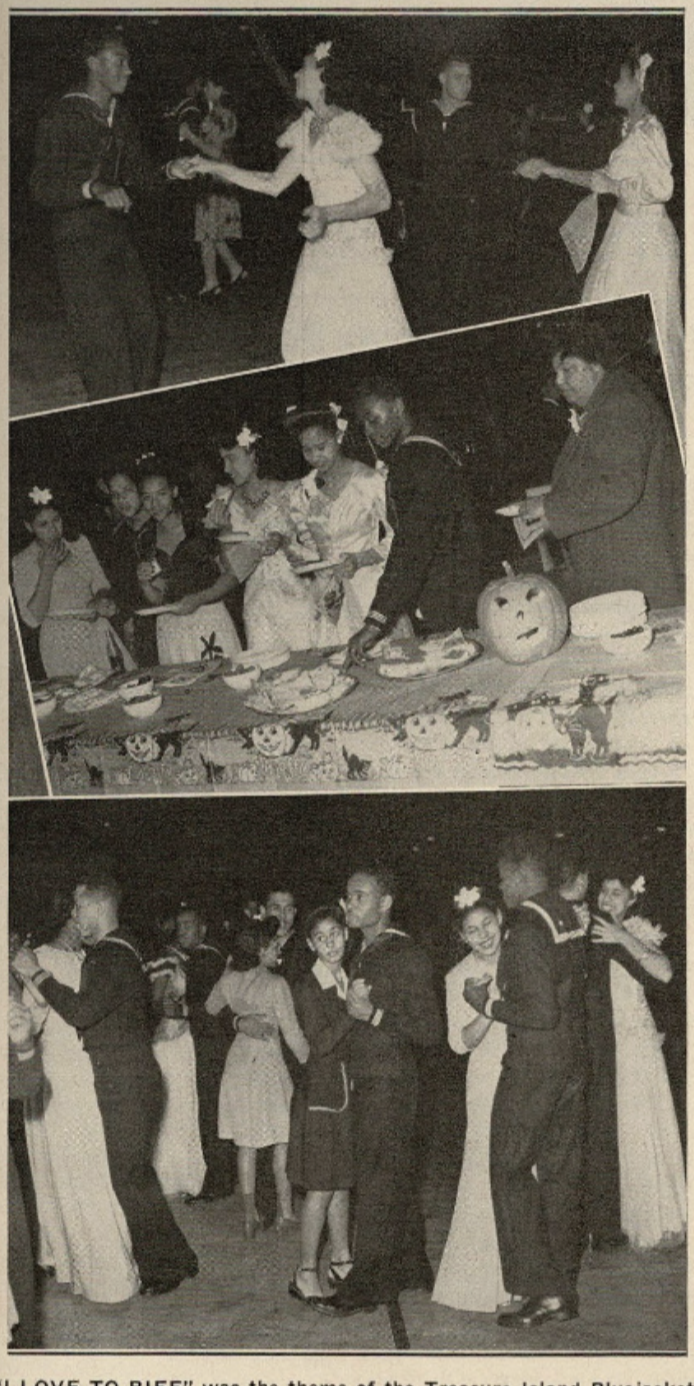

Two 1944 holiday events for Black personnel featured the band. At a big Halloween ball the band’s White leader, Bandmaster W.J. Fitzpatrick, led a Congo line, and a dance competition crowned the “king and queen of the rug cutters.”

Then at a post-Thanksgiving dance, the gym was packed again for a “jive session for colored personnel”–no dates allowed “but scores of Bay area hostesses available.”

The Masthead. 8 June 1945: 8. Courtesy of Treasure Island Museum.

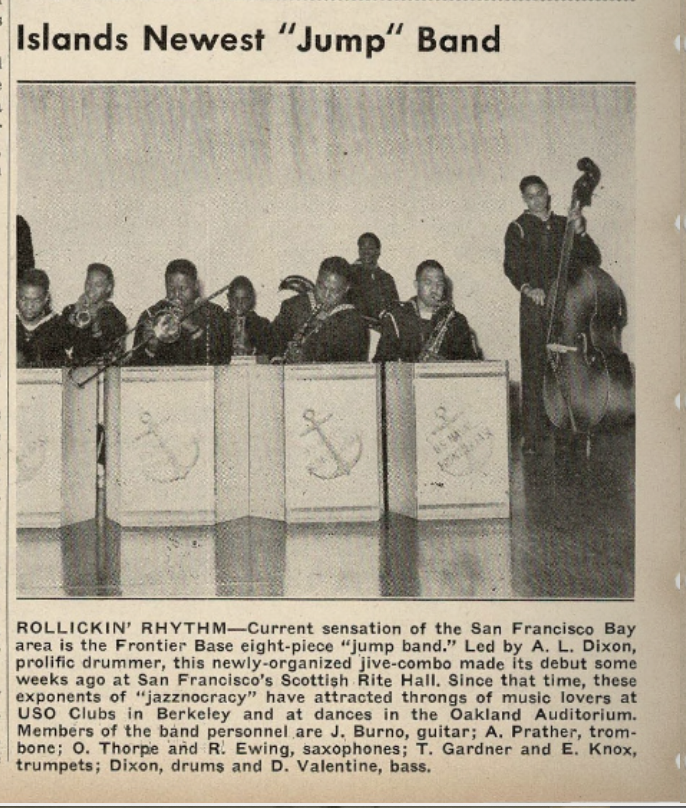

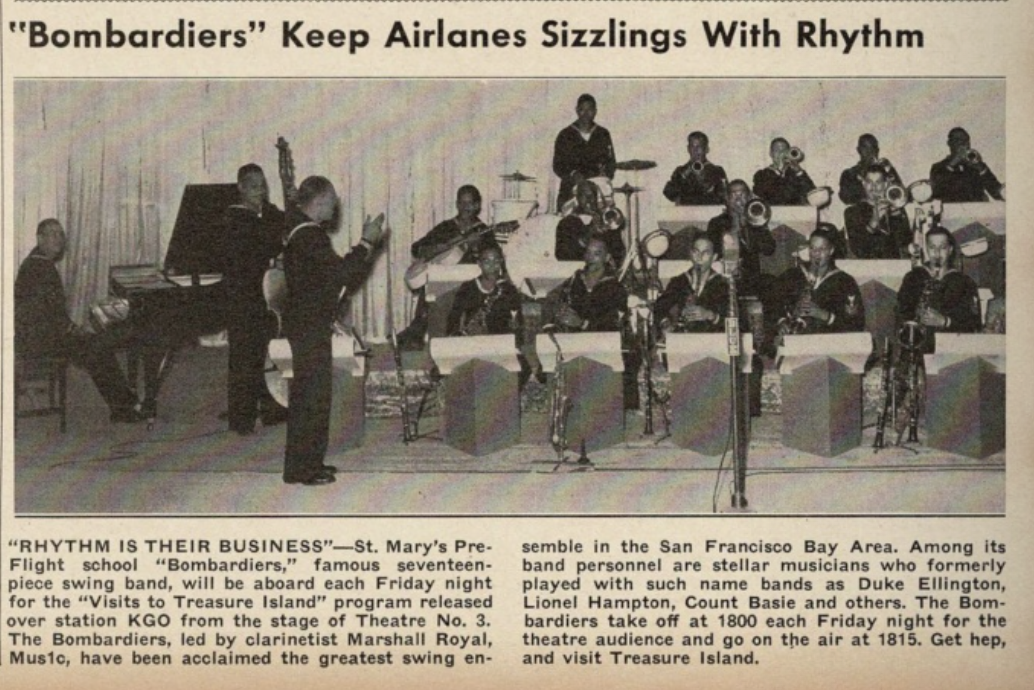

So great was the need for entertainment on base, and so full was the band’s schedule, that two additional bands–including the Radio Materiel School swing band–“an all-colored choir,” a “mixed choir,” and a glee club were formed from Bluejackets at T.I. To further supplement the band’s unavailability, other bands provided entertainment for dancers, smokers or special occasions, including the Armed Guard, an 8-piece band of White musicians noted for their jive playing; a Navy band led by Bandmaster Shapiro; “TadCen’s band,” from Camp Elliot at Shoemaker; the Fleet City Swing Band, a White band that also toured area bases with a USO show featuring Danny Kaye and Chico Marx; the Alameda Coast Guard band, based on another artificial island in the Bay, this one created in 1913 and originally called Government Island; the Air Transport Command Band, “generally considered one of the best”; the Frontier Base “jump band”; and the Bombardiers, who likely were the best band with the best swing band in the Bay area. In May 1945, they began performing at Treasure Island regularly on Friday nights–a schedule that may have helped bridge an entertainment gap between the first band’s departure and the second’s arrival.

Like the T.I. bandsmen, the Bombardiers had been recruited from the ranks of professional musicians who were promised service for the war’s duration at their duty station, St. Mary’s College in Moraga. The college’s Pre-Flight Training School was one of two Navy installations outside of Chicago to host a regimental band–40-44 pieces, large enough to break into two swing bands, which also performed at the Stage Door Canteen and at some of the area bases. But the band’s leader, Marshal Royal, tried to keep a low profile for his band, fearful that they’d be sent to the Pacific if they were noticed and found to be too good to stay stateside. His ploy may have worked; the band at St. Mary’s may, in fact, have been the only Black band to remain intact at its duty station for the duration.

–more story below this gallery f rom The Masthead–

The Masthead. 19 May 1945: 4. Courtesy of Treasure Island Museum.

The Masthead. 4 November 1944: 4. Courtesy of Treasure Island Museum.

The Masthead, 9 Dec. 1944: 4. Courtesy of Treasure Island Museum.

The Masthead. 3 Sept. 1944: 4. Courtesy of Treasure Island Museum.

The Masthead, 4 Nov. 1944: 4. Courtesy of Treasure Island Museum.

The Masthead, 12 May 1945: 7. Courtesy of Treasure Island Museum.

Courtesy of Treasure Island Museum

Courtesy of Treasure Island Museum.

• • •

Treasure Island’s Second Black Navy Band

Several T.I. bandsmen had been transferred before the band as a unit was sent back to Chicago for re-assignment. In June 1945, after 32 months at T.I., it was replaced by a band led by Clyde Kerr, a well-known music educator and leader of one of New Orleans’ best dance bands prior to the war. Kerr had first led a Navy band of New Orleans recruits who’d been promised service “for the duration” there, at Lakefront NAS. Alvin Alcorn, the lone New Orleans native in the first T.I. band, had likely enlisted thinking he’d serve with those fellows–he had played locally with Kerr.

Clyde Kerr. The Masthead, June 1945. Courtesy of Treasure Island Museum.

Kerr recalled working double duty while stationed at Treasure Island, taking care of the T.I. band and its swing band, the Shipmates of Rhythm, as well as composing and arranging for stage and traveling shows that featured musicians such as Harry James. The Shipmates of Rhythm also performed behind Humphrey Bogart, Betty Grable, and other Hollywood stars at the Stage Door Canteen, where Bettie Davis was in charge of booking musical acts. Kerr said that he worked with “just about all the best musicians in the country.”

The Shipmates of Rhythm provided music for the station’s weekly radio broadcast, “Skyway to Victory.”

Kerr and his band, designated B-755, were playing the “hottest jive” for a base dance almost as soon as they arrived. Only two of the new band’s players had been stationed in New Orleans with him, Leo Dejan and Emanuel Crusto. Its muster list names others whose previous duty stations are not currently known.

Kerr’s band proved just as popular at the Stage Door as the first T.I. band. It led base celebrations on V-J day and furthered the celebrating at San Francisco’s September 9 victory parade. It also continued performing with USO shows, including one led by Bob Hope, and other entertainments on base as the war machine wound down. One of its biggest events was a double-date dance held October 25-26 for Black bluejackets at the Oakland Municipal Auditorium, with over 2,000 attending each night.

In September 1945, a new 22-piece White band, B-126, arrived on base, its players veterans of Pacific Theatre service, and thereafter it alternated week by week with Kerr’s band the 0800 playing of colors until he and his band mustered out.

African-Americans on Treasure Island

If you read only the official Navy commemorative yearbook for Treasure Island, published in 1946, you’d not have guessed that African Americans had served there. Even its several photos of dances and dancers are all-White. It seems likely that had not The Masthead published a bad little joke that created a series of events that brought Robert E. Johnson to the base. The T.I. band had been in place for 18 months before Johnson “introduced” them in The Masthead. Prior to his arrival, The Masthead rarely mentioned “colored” sailors and never ran photos of them.

The swing band got one amusing notice prior to Johnson. At a “Paul Jones” dance, with 150 “lovely girls from the YMCA and Red Cross” brought in for partners, the paper reported the band “did a wonderful job of cutting the music into small pieces so that it could be digested by the sailors and their charming guests.” All other mentions of the band prior to Johnson’s arrival on staff refer to it as “Samuel Offenbach’s band”–Offenbach was their first White bandmaster.

Prior to his arrival on staff, The Masthead rarely mentioned “colored” sailors and never ran photos of them, except as boxers, usually from another base and unidentified. But during his time on staff, The Masthead published an astonishing amount of news directly aimed at a Black audience, and the band was the center of much of that news.

The level of control that Johnson exerted over layout is impressive, and he managed this nearly unbelievable headline: “Bandmaster W.J. Fitzpatrick Presented Stage Door’s Highest Award.” Fitzpatrick was an Army veteran before he joined the Navy who may have taken over as acting bandmaster after the band’s first White bandmaster was re-assigned but before their next White bandmaster arrived, but that’s difficult timeline to resolve. A more likely scenario would have the award presented to the man who was leading the swing bad on the day of the awarding, without the Stage Door realizing it was in a sense violating Navy protocol by giving it to a Black man, which suggests that the presentation of the award was not scheduled. Fitzpatrick and James B. Parsons, of Navy B-1 are the only two Blacks that I can verify led their bands and were known on occasion as “acting bandmaster.” Fitzpatrick may have been Bandmaster only for a day; Parsons kept his leadership role for the duration, despite two attempts by the Navy to replace him. Dropping the “acting” from Fitzpatrick’s title in the headline was a dare for clarification to the Navy, it might seem; the Bandmaster rank remained closed to Black bandsmen until well after the war.

Johnson would later write that he was named the first Black managing editor at The Masthead after it published a racist joke that caused trouble on the base. But as often seems the case, parts of the story can be substantiated while others don’t add up. The Pittsburg Courier reports in August 1943 that a racist joke printed in The Masthead “a few weeks ago” (July 17, on page 2, an untitled one sentence filler that manages to be offensive in at least three ways) brought about an official Navy apology. But The Masthead does not list Johnson as an editor until October 1944.

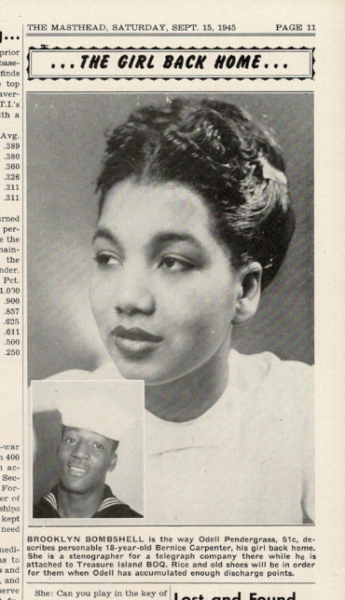

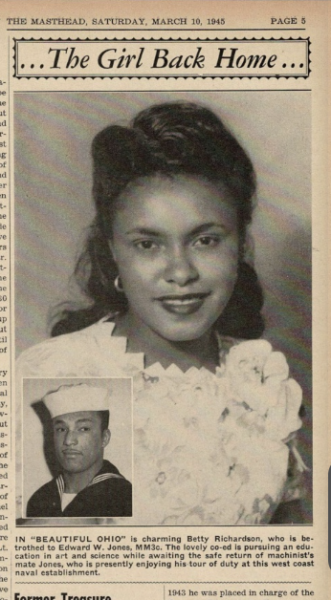

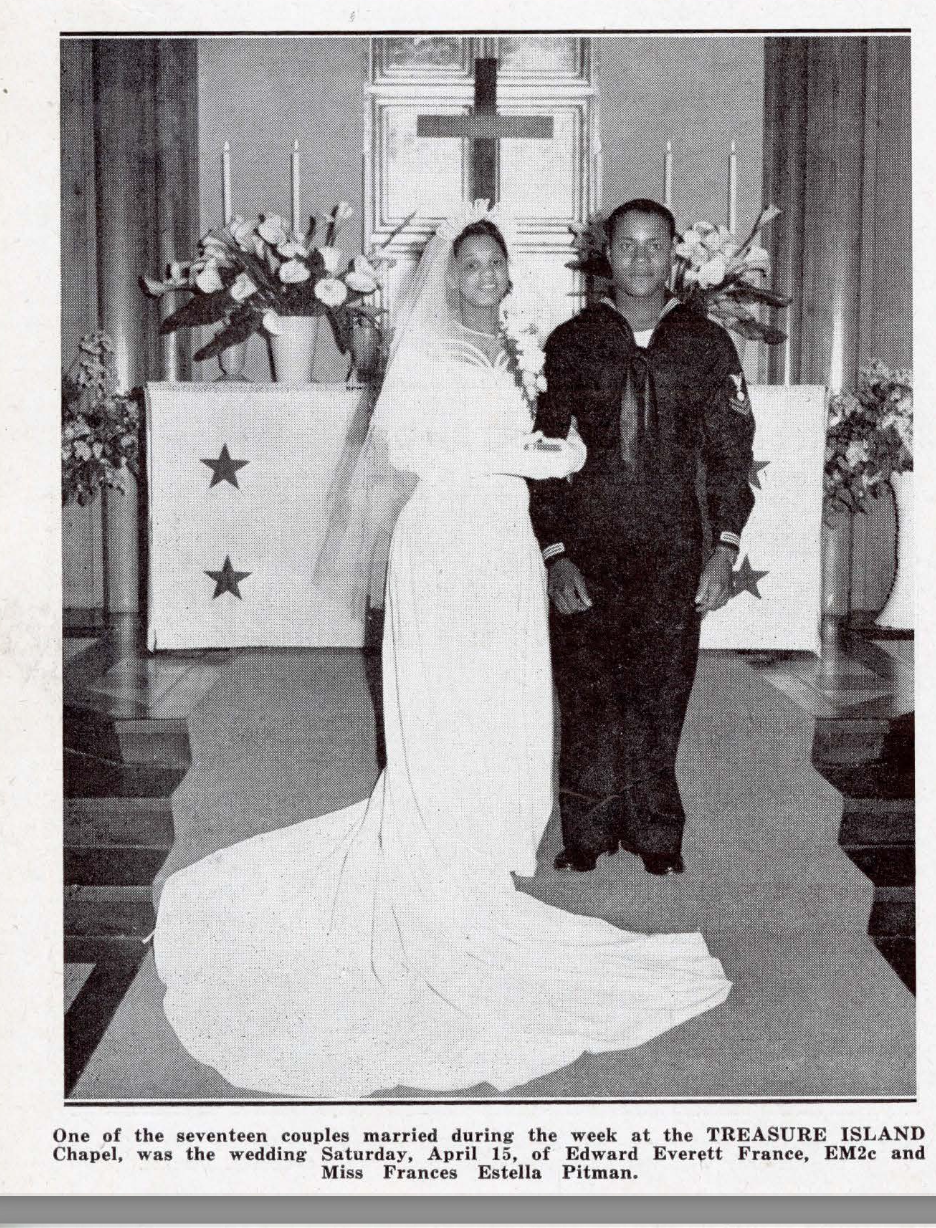

Regardless, after Johnson became associated with the paper it began covering Black sailor news on a regular basis, even running photos of Black sailors and their girlfriends. They are not signed but neither are they difficult to differentiate stylistically from copy in the rest of the issues. Missing still are copies of volume 1 and two issues from September 1945. What I’ve been able to locate begins with December 1942, volume 2, number 1.

Regardless, after Johnson became associated with the paper it began covering Black sailor news on a regular basis, even running photos of Black sailors and their girlfriends. They are not signed but neither are they difficult to differentiate stylistically from copy in the rest of the issues. Missing still are copies of volume 1 and two issues from September 1945. What I’ve been able to locate begins with December 1942, volume 2, number 1.

Coda

Which band was the best can’t be known, of course. In the Hawai’i theater of operations, Battles of the Bands regularly pitted three or four of the best from all the service bands in the area in wild and serious competitions. The San Francisco military band scene was more sedate, it appears–no battles, but plenty of interchanging of venues amongst the players.

In the club scene around San Francisco, a mixing of jazz styles and influences from Chicago, the West Coast, and New Orleans came especially from the players in the two Black Navy bands stationed at Treasure Island, the Bluejackets from Camp Parks, and the Bombardiers from St. Mary’s. It’s still unknown how many area bases had Black bands. Especially important when that occurred is whether or not the base allowed Black sailors to live on it. With the bands at St. Mary’, most of whose members lived in Black neighborhoods in the Bay area; Fleet City; and the two in New Orleans, the musicians lived in civilian housing, with a stipend, they were often happy to recall, and they had the tacit okay to play nightclub gigs if not in Navy uniform. On-base housing such as at Treasure Island kept them “home” at night.

This happy couple no doubt had Robert E. Johnson to thank for getting their photo in The Masthead. 15 May 1944: 4. Collection of the author.

• • •

A partial muster of Treasure Island’s Black Navy bandsmen and its White bandmasters

T.I. composers (L to R) Raymond Brown, Braxton Patterson & Samuel Allen, pianist George Matthews, and vocalist John Woodruff, who was also assistant producer for the Treasure Pleasure Time shows. The Masthead, 6 May 1944. Collection of the authorMuster Lis

Oliver Alcorn B-755 tenor sax, clarinet (October 3, 1910 – March 21, 1981)

Alcorn likely enlisted in New Orleans, believing that he would remain stationed there in one of the city’s two Black Navy bands. Where his first band was stationed is not known, and the musical career of his older brother Alvin (born in 1912), who played and recorded with Don Albert, is much better documented. The Alcorn brothers played and recorded with Papa Celestin’s Original Tuxedo Jazz Orchestra in New Orleans in the 1920s; Alvin remained a popular and respected musician there his whole life.

Oliver Alcorn, however, lived in Chicago after the war, where he recorded with Little Brother Montgomery, St. Louis Jimmy, Sunnyland Slim, Blind Willie McTell, and Muddy Waters.

The Alcorn Brothers were born to a musical family who lived in the 2800 block of Magnolia Street in New Orleans. In the 1920s, they played together in the Excelsior Brass Band, which Alvin called “a walking band” that seemed to play a jazz funeral a day.

Samuel Allen (January 30, 1909 – April 1963) played piano on many sides prior to the war, with the Teddy Hill and Roy Eldridge orchestras as well as with his own. Frank Driggs’ interview with him at the University of Missouri – Kansas City has not been transcribed or digitized.

Anderson, Clarence, piano B-755

Clarence “Sleepy” Anderson recorded several sessions with Gene Ammons, more often on organ than piano. Allmusic.com lists among musicians he collaborated with two who also played in Black Navy bands: Clark Terry in Chicago and Ernie Royal at St. Mary’s Pre-Flight School.

Albert Bartee, drums

An addition to the first T.I. band. After the war, he recorded with Illinois Jacquet and His Orchestra in Los Angeles in 1955, seven tracks of which appear on a Capitol re-issue Swing’s the Thing.

Johnny Board, with Al Grey’s All Stars, Buffalo Booking, Houston

Johnny Board B-755. 1919-1989. Saxophone.

A Chicago native and DuSable High School graduate, Board remained active in the city’s jazz scene until the 1980s. Prior to the war, he was playng with the Coleman Hawkins band and had been a runner up in the Esquire poll.

After the war, he played with Lionel Hampton, the Count Basie Orchestra, Woody Herman, B.B. King and Bobby Blue Bland.

Bosworth, Donald B. (White)

Chief Bandmaster Bosworth took charge of the first T.I. band in February 1945 after serving two years in the Aleutian Islands and South Pacific. He announced on arrival plans to recruit enough musicians to build a 46-piece regimental band on base.

David Brown, clarinet & arranger, began his music career in Chicago. He played for 9 years with the 10th Cavalry Regimental Band in New Mexico. Johnson identifies him as the band’s chief arranger, who’s also studying music at the University of California.

Raymond Brown

Identified by Johnson as a member of the first band.

James G. Buchanan, saxophone, studied music education at Alabama State Teachers College. Before the war, he also worked with Joan Lunceford and arranged several hits for Clarence Love. Johnson reports that he had written over twenty pop and patriotic songs being performed by the band.

Crusto, Emanuel B-755. Trumpet & arranger. Crusto was one of three excellent New Orleans musicians who were originally part of a Navy band stationed there.

Leo Dejan B–755, trumpet.

Born in New Orleans in 1911, Dejan began playing violin at 7, at 14 had his own band, and at 15 was leading the Moonlight Serenaders. In the ’20s, he led the Black Diamond Orchestra. He began studying pharmacy at Xavier University but was persuaded by a college dean to change majors to music. He graduated from Xavier in 1933. His brother, Harold, one of New Orleans’ most beloved musicians, played in New Orleans’ second Black Navy band, stationed at Algiers.

With the New Orleans Navy band, he earned Mus1c rating, the highest given to African-American bandsmen during World War II; it was not uncommon for Black bandsmen to have rank reduced when re-assigned, so I cannot say for sure that was his rank when he mustered out.

George Dixon (1909 – 1994) was a multi-instrumentalist born in New Orleans and educated at Arkansas State College. He learned violin firs but had had been playing saxophones and trumpet with Earl Hines and living in Chicago for the decade before World War II. The Chicago Defender in August 1942 said that he was joining the band bound for Treasure Island “soon” but his name doesn’t show up in The Masthead coverage of the band. Two online sources indicate that he led a Navy band at Naval Air Station Memphis, so he may well have been sent there instead of Treasure Island in 1942, or he may have gone to Memphis after a stint at T.I., or another base. Given his credentials, it seems unlikely he would have gone unnoticed at T.I.

Richard Dunlap, trombone, became a pro “at an early age,” Johnson writes. A member of the first T.I. band, he had played with Louis Armstrong and Fats Waller before the war.

Leonard Fields, alto saxophone, was an addition to the Treasure Island band in 1943. He was noted as “trumpet soloist.” He wrote the lyrics for the 1919 hit “When the Yanks Come Marching Home” and had played with Jelly Roll Morton’s band, where he was known to be paid “higher than the usual salary because of his all-around musicianship.” A native of Louisville, Kentucky, he grew up next to trumpeter George “Little Mitch” Mitchell, who took lessons from Fields’ father. Leonard Fields studied in Chicago where he became noted for his prowess on both trumpet and saxophone. Ed “Boogie” Morton recalls Fields playing sax in clubs in Louisville. Bobby Booker, who played trumpet in a band in which Fields played alto, said of him: “I never saw anybody play like him, he was really fast and used to do double and triple tongue work on the saxophone.”

Fields first began playing music in New York, then studied at the University of Chicago (or Chicago Musical College) before working with Fletcher Henderson, then Fats Waller, and Johnny Long. Johnson notes that in addition to arranging for the band, he was studying music education at the University of California while working at Treasure Island.

William J. Fitzpatrick, trumpet, acting bandmaster.

Fitzpatrick studied instruments at Wendell Phillips High School in Chicago and at Lincoln University. Prior to the war, he toured with his twin brother as a dancing team, and before that was a trumpet soloist in the 8th regiment Army band for five years. He was an original T.I. bandsman and one of two Black Navy bandsmen to act as bandmaster, although that rank remained officially closed to them.

Alphonso Fook played trombone in the first T.I. band and recorded with the Jay McShann band after the war.

Lawrence Fulgham

Pomp Hobson / Holman, a “suave guitarist,” was in the original T.I. band.

Henry Hogan

Identified by Johnson as a member of the first band.

Wilbert Hughes

Identified by Johnson as a member of the first band.

Wilfred P. Jackson

Identified by Johnson as a member of the first band.

Thomas Johnson 755 alto saxophone

Martin V.B. “Van” Kelly, Jr., a “stellar clarinet artist,”was born in Pittsburgh on February 23, 1921 and graduated from Allegheny High School. In 1942, he married Lettie B. Hyde, became a member of Ebenezer Baptist Church, and joined the Navy, training at Great Lakes prior to service with the Treasure Island Navy band. AHe was one of the most prolific arrangers in the original T.I. Band. fter the war, he became one of the first African Americans admitted to the Navy’s School of Music, where he studied conducting and advanced saxophone and clarinet. He returned to Chicago and played with trumpeter Eddie Mallory and then moved to New York where he performed with the Charlie Barnett Band at the Savoy Ballroom and the Apollo Theater. He traveled as part of Eddie Rochester’s troupe and then returned to Chicago, where he played in the Billy Eckstine Band with Miles Davis, Gene Ammons, Art Blakey, and Frank Wess, occasionally gigging with Cab Calloway. In 1952, he earned a B.S. in biology/ chemistry from Roosevelt University and became a medical lab director with the Veterans Administration. After retiring in 1992, he picked up his musical interests full-time, forming the Van Kelly Trio, which was the house band at the Como Inn for five years. He recorded with Floyd McDaniel and the Blues Swingers. After moving to Hilton Head Island in 2001, he performed with several Low Country bands, including the Stardust Orchestra and a Dixieland band that played monthly gigs at the Jazz Corner on Hilton Head, where he died on November 22, 2012.

Kerr, Clyde. B-755 Leader of the second Black Navy band at T.I., Kerr had led a similar band in his native New Orleans; they’d all been promised service at a Lake Ponchartrain Naval base for the duration but were broken up and sent back to Camp Smalls in 1944 for re-assignment.

Howard “Slim” Liggins / Loggins, drums, in the first band.

George Matthews (September 23, 1912 – June 28, 1982) was born in Dominica and moved to New York (or New Jersey) with family when he was a child. He started playing at Bordentown, NJ. He studied tuba, trumpet, and trombone at the Martin Smith School of Music. Johnson writes that he was discovered by Louis Armstrong and featured with him before joining Chick Webb, with whom he played after Webb’s death with Ella Fitzgerald; he also played with Willie Bryant, Cannonball Adderly, Ray Charles, Clark Terry, Count Basie, and Dizzy Gillespie.

Frank Driggs’ interview with him at the University of Missouri – Kansas City has not been transcribed or digitized.

Ernest McDonald, tenor

Herman Mitchell, “the little man with the big bass fiddle,” began playing music when he was 8. He studied violin, bass violin and bass horn and before the war played with the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra and swing music with Don Clinton’s orchestra. He was a member of the first T.I. band.

W.J. Nelson B-755 [White], chief bandmaster for 2nd T.I. Black band.

Samuel Offenbach [White]

First Black band’s first bandmaster.

Arthur L. O’Neil, tenor sax in original T.I. band.

After the war, he returned to Chicago, where, known as Swinglee O’Neil, he mentored many young musicians. His son, Avreeayl Ra, was born in 1947 and remains active in the Chicago jazz scene after a career playing with Professor Longhair, the Sun Ra Arkestra, and others.

Joseph R. Page, trumpet, studied music at Tilden Technical College in Chicago and at Alabama State Teachers College, where he earned a B.S. and was a member of the renowned Bama State Collegians, with whom he toured prior to induction.

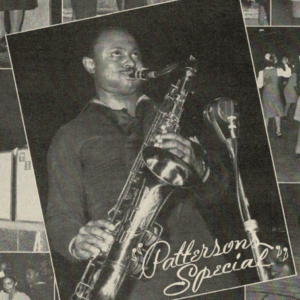

Braxton Patterson B-755, sax, began as a drummer. He was playing with the Louisiana Swingsters before joining the Navy, and arranged “Baby It’s You” for J. Russel Robinson. in Rochester, NY. He played saxophone with Noble Sissle’s orchestra prior to the war–Sissle preceded him to T.I., where he brought his USO show “Keep Shufflin'” in 1943. Patterson was known at Treasure Island for his playing as well as his arranging.

Braxton Patterson B-755, sax, began as a drummer. He was playing with the Louisiana Swingsters before joining the Navy, and arranged “Baby It’s You” for J. Russel Robinson. in Rochester, NY. He played saxophone with Noble Sissle’s orchestra prior to the war–Sissle preceded him to T.I., where he brought his USO show “Keep Shufflin'” in 1943. Patterson was known at Treasure Island for his playing as well as his arranging.

Ike Perkins

Earl Philips

Melvin L. Saunders, principal drummer in the first T.I. band and the regular drummer with the swing band, he began as drummer in 4-piece band in Des Moines, IA. He studied at Englewood High School in Chicago, where he organized his own band and also played in concert bands under Major N. Clark Smith, E. Stirman, and Norman Black. He began his professional career with Eddie Barefield and played with Earl Hines before the war. He was instrumental in recruiting the Treasure Island band.

Ray Saunders,

Thomas Scates, trombone, began playing music with high school band and before the war was known for freelance work with bands led by Doc Wheeler, Baron Lee, King Kolax, and Blanche Calloway.

Bill Sylvester

Albert Verdun [?]

Identifid by Johnson as a member of the first band.

Edward W. Walker, trumpet, began studies of music in Los Angeles. He freelanced with Eddie Barefield, Happy Johnson, Kenny McVey and Coleman Hawkins and also worked with Cootie Williams, King Kolax, Ernie Fields, and the Bill Robinson Show.

Henry Williams

• • •

Sources

Alcorn, Alvin. Interview with Richard B. Allen, 30 Nov. 1960. Hogan Jazz Archives, Tulane U, New Orleans.

Allen, John. Email to author. 24 Nov. 2017.

Arbona, Javier. “Anti-memorials and World War II Heritage in the San Francisco Bay Area: Spaces of the 1942 Black Sailors’ Uprising.” Landscape Journal: design, planning, and management of the land. 34.2. 2015. Web: Project Muse. 8 Feb. 2025.

“Avreeayl Ra.” Chicago. n.d. 3arts.org. 14 Feb. 2025.

Booker, Bobby. Interview with editor and Frank Driggs, in Hot Jazz: From Harlem to Storyville, ed. by David Griffiths. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow, 1998.

Curran, David. “Why a 7-mile-long steel net once ran under San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge.” SF Gate. 26 October 2023. 10.26.23

“Eleven Hollywood Stars Here.” The Masthead. Treasure Island Naval Station. 3 Mar. 1943: 1. treasureislandmuseum.org. 2 Feb. 2025.

Fries, Carson. “Port Chicago Naval Magazine Explosion, 17 July 1944.” Naval History and Heritage Center, 2019. www.history.navy.mil. 9 Feb. 2025.

Gavin, Thomas. Fayetteville, NC. Interview with author. xxxx 1987.

Graves, Donna. “Project PRISM.” Richmond Planning Department. Richmond, CA, 2009.

Johnson, R.E. “Bandmaster W,J. Fitzpatrick Presented Stage Door Canteen’s Highest Award.” The Masthead. 2 September 1944: 4.

—.“Gala Cast of 100 in Show, Treasure Island’s Band Features an Array of Talented, Famous Musicians.” The Masthead. 8 April 1944: 1, 4.

—. “Rehearsing more than 600 orchestrations keep T.I. Musicians Busy.” The Masthead. 24 Feb. 1945: 4.

Kennedy, Al. Chord Changes on the Chalkboard. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow, 2002.

“Leonard Fields.” Chicago Defender [Nat’l ed]. 6 Mar. 1943: 10.

McDevitt, Rear Adm. E.A., ed. The Naval History of Treasure Island. US Naval Training and Distribution Center. Treasure Island CA. 1946. Internet archive. 1 Feb. 2025.

“Martin V.B. ‘Van’ Kelly, Jr.” Obituary. Legacy.com. 9 Dec. 2012. Web. 6 June 2013.

The Masthead. January 1943 – December 1945. TreasureIslandMusuem.org/Masthead and collection of the author.

Morton, Ed “Boogie.” “I’ve Got a Mind to Ramble.” Interview with Keith S. Clements. Louisville Music News, March 2005. Web. 9 June 2021.

Murray, James. “Vallejo Negroes Have Finally Found a Place Like Home. San Francisco Chronicle. 19 Aug. 1943: 7.

Naval Receiving Station, Transient Personnel, U.S. Naval Training Center [TADCEN]. vol 25, 1945. GGArchives.com. 11 Feb. 2025.

“Navy Apologizes for Joke.” Pittsburg Courier 28 Aug. 1943: 8.

“Navy Band Is about Set with Name Aces.” Chicago Defender 15 August 1942: 23.

“Oliver Alcorn.” ArtistInfo. Music.metason,net. n.d. Web. 14 Mar. 2023.

“Parade to Celebrate California’s Birthday.” San Francisco Chronicle. 9 Sept. 1943: 17.

Pizzimenti, Joe. Email to author, 15 Mar. 2017.

White, Byron P. “Robert Edward Johnson, Jet Associate Publisher.” Chicago Tribune 28 Dec. 1995. Web. 17 July 2014.

Wicks, Steefenie. Telephone interview with author. 13 Mar. 2014.

“WW II. Treasure Island History.” TreasureIslandMuseum.org. 22 Dec. 2024.

active revision in process

–February 13, 2025