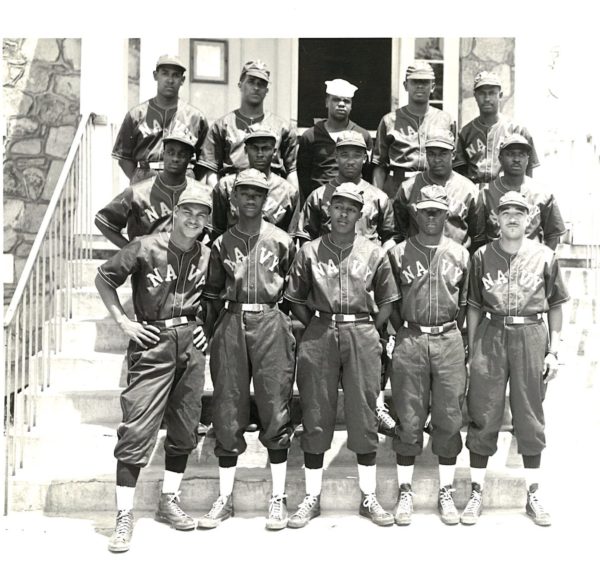

The band at Great Lakes, shortly before assignment to replace B-1 at Chapel Hill. Courtesy of David Martin Brown & US Navy Band Archives.

UNC-‘s 2nd PreFlight Band:

Replacing B-1, May 1944

B-1 bandsmen didn’t find out they were being transferred to Pearl Harbor until their replacements, who had been trained at Camp Robert Smalls, arrived during the third week of April 1944. The new bandsmen came from “widely separated places,” the pre-flight school’s newspaper Cloudbuster reported, after they began arriving for duty on April 20, 1944. For most, Chapel Hill was to be their first duty station.

It was an active week in Chapel Hill, as 37 new bandsmen were received from Great Lakes on April 20 and five more within a week; B-1 got on their train for Shoemaker on April 24. Three more musicians arrived in May and a couple had been sent elsewhere, but the core of a 40-piece band had been established by June 1944. On June 2, they were welcomed to their new barracks, at the Hargraves Street Community Center where B-1 had been housed, with a banquet and dance. They also stepped right into the routines and performance schedules established by B-1, playing for the PreFlight School cadets and officers, and at patriotic events throughout the area.

The replacements, like B-1, were a regimental band, with a performing number of 40-44 players. Of the 100 or so Black Navy bands, only a handful were full-size regimental bands, which were necessary for large ceremonies with high ranking dignitaries in attendance; all four pre-flight schools hosted regimental bands, those at UNC-Chapel Hill and St. Mary’s College were all-Black bands; those at the universities of Iowa and Georgia were all-White. The Navy also kept at least two Black regimental bands operational at Great Lakes during the war. Otherwise, most bands attached to naval bases had 20-22 players.

Locals recall that the new bandsmen were different from B-1: older, and unused to the Jim Crow system that dominated Chapel Hill. Unlike the B-1 bandsmen, who for the most part spent their leisure hours in and near their Hargraves Center barracks, many of the replacement bandsmen enjoyed visits to Durham’s Hayti community, for its nightlife.

The following narrative has on several occasions conflated the two Black bands, so that B-1 is recalled as the “troublemaker” although they were long gone when a few Black Navy bandsmen were seen walking with White girls coming home from a Sunday afternoon picnic in July 1944 at Battle Park. The picnic was organized by the “Snuffbuckets,” an integrationist group of UNC students associated with Rev. Charles Jones’ Chapel Hill Presbyterian Church, and its group also included three students from North Carolina College in Durham (the HBCU now known as North Carolina Central University), two Black women, and one Black man.

Chapel Hill police reported the event, and the local community’s outrage over it, to an F.B.I. informant, which prompted the War Department to prepare its confidential memo “Commingling of Whites and Negroes at Chapel Hill, N.C.” The police reports were “inaccurate accounts” that made it clear that “police were spreading false rumors about [Rev.] Jones and his church,” and insinuated that UNC President Frank Porter Graham and Dean of Students Francis Bradshaw were part of the problem. The “Commingling” report complained that “the coeds and negroes were seen walking side by side on the streets of Chapel Hill on this particular day” and warned that “serious trouble could develop.” Rev. Jones said the complaint should be “dismissed at once.”

Because Chapel Hill police were known to wait for the bandsmen to come back from Durham, some of them invariably intoxicated and thus subject to harassment and arrest, Rev. Jones took to waiting for them at the bus station on weekend nights, so that he could escort them safely back to their barracks. His house was egged, he no doubt faced other threats, and some in the Chapel Hill community still believe his progressive attitudes towards integration cost him his pastorate. He went on to become founding minister for Chapel Hill’s Community Church.

The 2nd Chapel Hill band called itself the Cloudbusters, using band stands from B-1’s tenure there. Courtesy of David Martin Brown & US Navy Band Archives.

The band’s glee club entertains at a welcoming dinner given in the band’s honor, June 2, 1944. Courtesy of David Martin Brown & US Navy Band Archives.

The band’s promotional pose was similar to one used for B-1 dance band of the same name. Courtesy of David Martin Brown & US Navy Band Archives.

The band was first directed by Chief Musician Chancey S. Seeley, a White 20-year Navy veteran who had spent most of those years at sea, and then another White chief musician, Ernest G. Smart. It included these African-American musicians:

Jasper Ward Allen, Sr. (1923 – ) bass

Enlisted November 16, 1942 in Chicago and was honorably discharged in February 1945.

“Jap” Allen led his own territorial band working out of Kansas City for about a decade, beginning in the mid-1920s. He also played bass with King Kolax in 1938-39. He was a member of the Ship’s Company A Band at Camp Robert Smalls, Great Lakes, before being sent to Chapel Hill, where he arrived as Mus2c on April 20, 1944.

James Drew Bailey (1915 – )

Enlisted January 12, 1944 at Chicago; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Thomas Samuel Baylor (1925 – ) trombone

Enlisted January 31, 1944 at Richmond; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Shelton Eugene Booth (1925 – )

Enlisted February 22, 1944 at New York City; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

David Martin Brown (1916 – ) trumpet

James Harold Brown (1915 – ) guitar ?

Enlisted January 26, 1944 at New York City; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Wallace Edwin Burrell (1926 – )

Enlisted February 23, 1944; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

William Kenneth Chapman (1910 – ) vibes, drums, vocals

Enlisted January 14, 1944 at Omaha; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Paul Bruce Coman, Sr. (1916 – ) trombone

Enlisted January 30, 1944 at Anniston, Alabama; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

He was a student of the legendary Birmingham bandmaster Fess Whatley, who funneled several of his students into the Navy, often with the assistance of one of his early Tuskegee Institute collaborators, Len Bowden, who was a principal recruiter of Black musicians for the Navy.

Coman was inducted into the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame in 1983.

Harry John Curtis (1910 -) alto saxophone

Enlisted February 15, 1944 at Washington DC

Curtis played alto sax. He recorded with Trummy Young in Chicago in the spring of 1944, just prior to entering the Navy.

Sidney Dawson (1925 – )

Enlisted April 12, 1943 at New Orleans; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Frederick Willis Ellison (1916 – ) tuba

Enlisted Feb. 18, 1944 Pittsburgh; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Carl Fields, trumpet

Enlisted Feb. 24, 1944 at Cleveland; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Samuel Louis Finly, Jr. (1910 – )

Enlisted Oct. 8, 1942 Columbia, South Carolina; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Samuel Floyd notes that Finley was a Juilliard School of Music graduate; he was Mus2c when he arrived in Chapel Hill.

L.C. Fitzpatrick (1912 – ) baritone

Enlisted July 23, 1943 at Chicago; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Clarens Laeon Porter Francois (1902 – ) piano ?

Francois was the piano accompanist on a 2-lp Life of Paul Laurence Dunbar recorded by Taffy Douglass in Dayton, Ohio. Liner notes indicate that he was a graduate of Northwestern University and had done graduate work at the University of Southern California. He taught at Palmer Memorial Institute in Sedalia and in Dayton Public Schools from 1933 until his retirement in 1968.

Ernest Benjamin Franklin (1902 – )

Enlisted Jan 29, 1944, Chicago; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Andrew Lee Gardner (1916 – ) saxophone

‘Goon’ Gardner was another of the many Chicago jazzmen who played in Navy bands, but he was already a veteran player when he joined in April 1944. By 1935, he was in one of King Kolax’s first bands (along with Nat “King” Cole), and worked for several years with Kolax, who led one of the most popular territory bands of the 1930s, and called Gardner “the baddest alto sax player in Chicago.” He recorded with trumpeter Roy Eldridge in November 1943. In the decade after the war, he appeared on about a dozen recordings, including sessions with Dinah Washington, in 1947 and T-Bone Walker in 1955.

Ivan Harris Glenn (1906 – )

Enlisted June 28, 1943 in Chicago; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

George Alonzo Goldsby (1915 – )

Enlisted January 15, 1944 in Detroit; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Gryce, George General, Jr. (Nov. 28, 1925 – March 14, 1983) clarinet

Clarinetist Grice, later known as Gigi Gryce, alto saxophonist, is the subject of the 2002 biography Rat Race Blues: The Musical Life of Gigi Gryce, by Noal Cohen and Michael Fitzgerald, who document his post-Navy career as a composer arranger, bandleader, and performer. During the 1950s, he worked with Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Max Roach, Clifford Brown, Art Farmer, Lionel Hampton, Quincy Jones, and Oscar Pettiford, among others. But, “Within a decade of his first commercial recordings,” they write, “he had slipped into obscurity, remerging with a new identity and a new career in education that would last twice as long as his jazz activities.” He changed his name to Basheer Quism, a Muslim name he used as early as 1955 and exclusively after he began teaching school, primarily at a South Bronx elementary school that was subsequently named for him.

Gryce grew up in a supportive and musical family that also attended Allen Chapel AME Church. His first formal music instruction was from his high school band directors and a local Federal Music Project program. The Booker T. Washington marching band, in which Gryce played clarinet, won a state music festival competition in Tallahassee just prior to the bombing of Pearl Harbor. He graduated from high school in June 1943 and worked in a shipyard and played in a local band

He enlisted in the Navy at Jacksonville, Florida, on April 3, 1944, as an apprentice seaman. At the conclusion of his training, at Great Lakes, he was promoted to Seaman 2c on May 8; 4 days later, his rating was changed to Mus3c (he likely tested into this rating, as did Lou Donaldson and others who had volunteered at a non-Musicians rating), and within a week he was in Chapel Hill, where in June 1945 he was promoted to Mus2c. He was among a group of musicians sent to the Navy’s School of Music in October 1945 for a short course of instruction before they were returned to Naval station duties. Gryce was then assigned to Kodiak, Alaska, where he was discharged in early 1946.

Cohan and Fitzgerald have compiled a thorough Gryce discography. Mike Fitzgerald has also been generous in his sharing of Navy enlistment records they uncovered during their research, and as a result, the second Chapel Hill band is among the best documented in terms of players of all the Black Navy bands of World War II.

Robert Lee Hopkins

Enlisted January 29, 1944 in Anniston, Alabama; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Aaron Carroll James

Enlisted February 10, 1944 in St. Louis.; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

McClellan Joseph Johnson

Enlisted February 11, 1944 in Washington, D.C.; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

James Charles Lightfoot (1918 – ) guitar

Enlisted November 25, 1943 in Washington, DC; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Lawrence Edgar Lucas (1925 – )

Enlisted February 16, 1944 in Richmond; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Russell McGinnis (1911 – )

Enlisted December 30, 1943 in El Paso Texas; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Theodore Lannett Mack

Enlisted January 13, 1942 in Little Rock; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

William H. Miller

Enlisted January18, 1944 in New York; arrived Chapel Hill Apru 20, 1944.

Malvin Moore, III is on back row, far left. “Behind the Veil.” Duke University Archives & Manuscripts.

Malvin Earl Moore, III. (1918 – )

Enlisted December 28, 1944 at Little Rock; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Thomas Gavin of B-1 said that Moore was his dean at Fayetteville State University when Gavin was organizing FSU’s band. Gavin recalled that Moore was from Tennessee and had earned a PhD at the Peabody Conservancy.

The Navy announced him with the band as Malvin Moore, Jr. The photo at left is a detail from a shot of the band’s glee club performing at a bond rally, likely in Durham. The larger photo from which it is taken (see bottom of this page) is part of a 14-slide collection that the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke acquired from Malvin Moore, III, and which became part of Duke’s Behind the Veil exhibition.

John Otis Paris, Jr. (1917 – ) trumpet

Enlisted February 24 ,1944 in Cincinnati; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Julius Oscar Pogue (1914 – ) tenor saxophone

Enlisted October 6, 1943 in Washington, DC; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Frank Lorenzo Poole (1911 – ) trumpet

Enlisted January 30, 1944 in Anniston, Alabama; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

James Mathew Reeves (1919? – ) bass

Enlisted February 16, 1944 in Richmond; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

A Norfolk native, Reeves graduated from Booker T. Washington High School in 1937 and from Virginia State College [now Norfolk State University]. He taught public schools in Upper Marlboro, MD, and then worked at the Norfolk post office until January 1944, when he joined the Navy. A Congressional tribute to him (House Resolution 79, February 23, 2011) said that he attended the Navy’s School of Music at Anacostia, MD–where he was sent with most of this second band after the war ended for a refresher course. His 30-year career teaching at Virginia State included chairing the Department of Music. He integrated the Norfolk Symphony (later the Virginia Symphony) in 1966, playing first chair string bass he retired, until 1981.

Reeves recalled, “I had tried out under Edgar Schenkman, who said ‘You play all right, but you don’t play head and shoulders above everyone in the orchestra, so I can’t justify taking a Black into the orchestra.'” At his first rehearsal: “I felt like I was ostracized by just about everyone in the orchestra. Nobody talked to me except the first bass player when he told me what to do. It took, I guess, a year or so before people seemed to have warmed up to me.” Reeves quickly worked his way up to principal, a post he held until his resignation in 1981.

— “Russell Stanger: Portrait of an American Conductor.” Old Dominion University. exhibits.lib.odu.edu. 23 Feb. 2025

George Riley Roberts (1917 – ) piano ?

Enlisted Dec. 14, 1944. Minneapolis; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Chancey Servis Seeley (1907 – ) conductor

The replacement band’s director, Seeley, who was White, was rated as Chief Musician when he arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Earl Edward Shepherd (1921 – )

Arrived at Chapel Hill as Mus2c in May 1945.

Richard Melvin Slater (1922 – )

Enlisted January 31, 1944 in Allentown, Pennsylvania; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Ernest Glenn Smart, conductor

Smart, the replacement band’s second director, arrived at Chapel Hill August 30, 1944.

Paul Nathaniel Smith (1925 – )

Enlisted January 28, 1944 in Chicago; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Erald C Clifford Trottman (1907 – ) euphonium

Enlisted September 13, 1943 in New York; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Robert Turner, Jr.

Enlisted January 27, 1944 in Anniston, Alabama; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Edwin Herndon Williams (1925 – )

Enlisted January 26, 19444 in Chicago; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Willie Berry Wilson (1911 – )

Enlisted February 1, 1944 in San Francisco; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

James Mosby Woods (1912 – )

Enlisted January 8, 1944 in Chicago; arrived at Chapel Hill April 20, 1944.

Sources:

Campbell, Robert L., Armin Büttner, and Robert Pruter. The King Kolax Discography 28 Apr. 022. Web. 5 May 2025.

Cohan, Noal and Michael Fitzgerald. Rat Race Blues: The Musical Life of Gigi Gryce, 2nd edition. Rockville, MD. Current Research in Jazz, 2014.

Clark, Rebecca. Personal interviews. Chapel Hill, NC. 30 Aug. & 17-18, July 2008.

“The First Party.” Photo caption. Cloudbuster 10 June 1944: 4.

Fitzgerald, Michael. Email to author. 5 May 2025.

Gavin, Thomas. Personal interview. Fayetteville, NC. 12 June 1986.

Giduz, Roland. Personal interview. Chapel Hill, NC. 16 July 2008.

Jones, Rev. Charles. Personal interview. Chapel Hill, NC: July 1986.

“Pre-Flight Band Leaves for Duty Outside Country.” Cloudbuster 29 Apr. 1944: 1, 3.

Pryor, Mark. Faith, Grace and Heresy: The Biography of Rev. Charles M. Jones, Lincoln, NB: iUniverse, 2002.

Tyson, Tim. “African American Militancy in North Carolina during World War II,” in Democracy Betrayed: The Wilmington Race Riot. Tyson and David Cecelski, eds. Chapel Hill: UNC P, 1998: 253-76.

–May 5, 2025

The band’s choir, in downtown Chapel Hill. Courtesy of David Martin Brown & US Navy Band Archives.

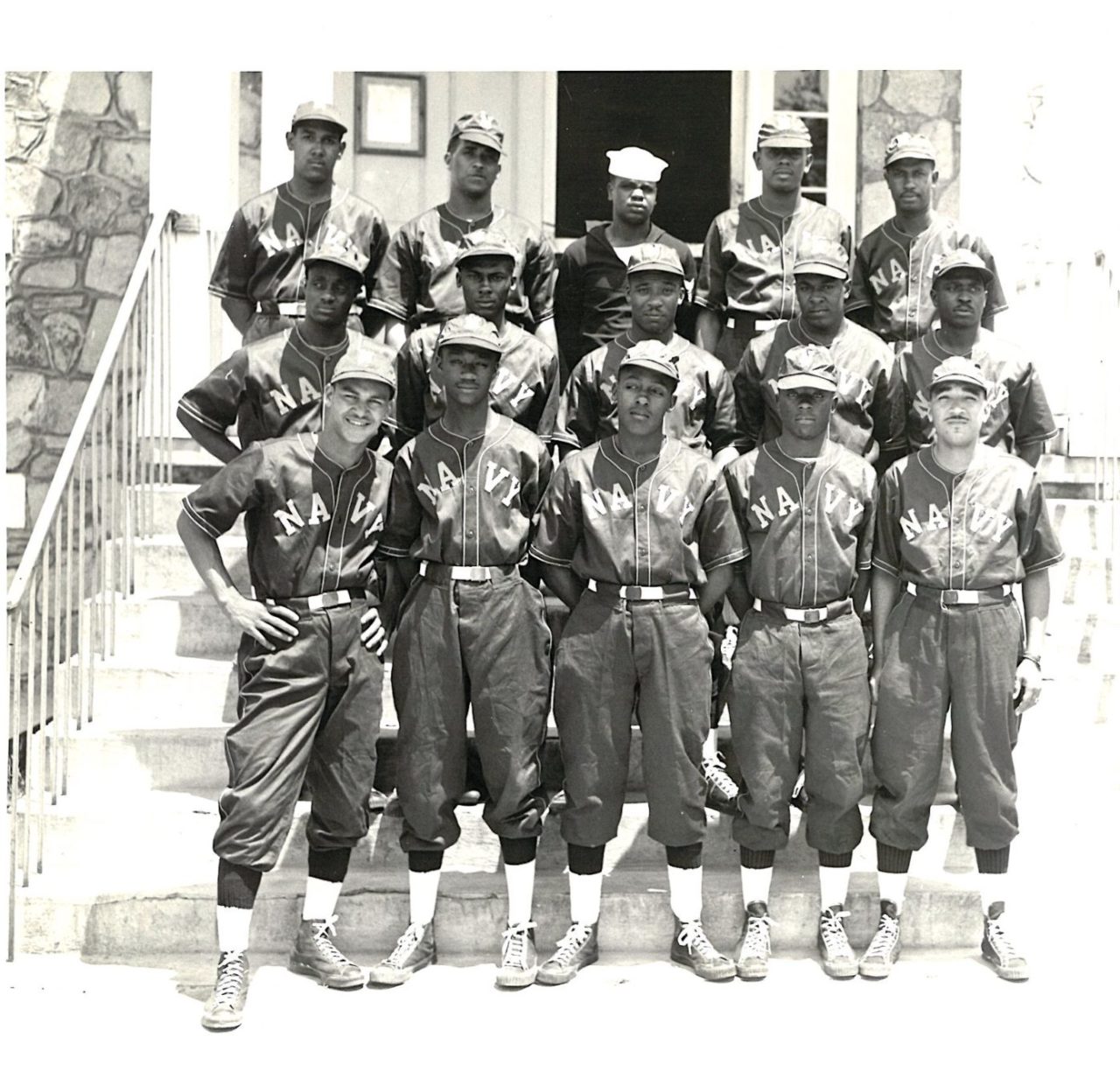

The band’s baseball team, on the steps of their Roberson Street barracks. Courtesy of David Martin Brown & US Navy Band Archives.

Malvin Moore, III collection of slides.”Behind the Veil.” Duke University Archives & Manuscripts.