Louis Armstrong in New Orleans 1931 – 1942

Louis Armstrong’s August 1942 performances at the Victory Arena and the Gypsy Tea Room marked the fifth time he had brought a band to New Orleans for performances since leaving for Chicago in 1922. His first homecoming, in 1931, lasted all summer, and his arrival in early June, he said, was “the happiest day of my life.”

He also brought bands to New Orleans for shows in 1935, 1938, and 1940.

Ξ Ξ Ξ

1931

For Armstrong, 1931 was a hectic year, already full of drama and action before his New Orleans homecoming. Since joining King Oliver’s band in Chicago in August 1922, he’d become the most popular and highest paid Black musician in America. By 1929, fronting Luis Russell’s orchestra but everyone calling it his, he ruled the Chicago and New York music scenes: after five months at the Savoy in Chicago that year, he barnstormed to New York at the “suggestion” of a mobster, where he headlined at Connie’s Inn and performed nightly on Broadway in Hot Chocolates of ’29. Despite apparent mob interference and arguments over his contracts and representation, he stayed busy and popular, in recordings and New York and Chicago performances, and in May 1930 he began an extended gig in Los Angeles–at Frank Sebastian’s New Cotton Club–that would run until mid-1931.

He left Los Angeles in April 1931 for Chicago, where he formed his first band made up “on purpose,” he said, that is, not ready-made by someone else. That band, as listed by Chicago Defender columnist and bandleader Walter Barnes [and cross-referenced with Jackson’s memoir]: Preston Jackson, trombone; Zanda [Zilner] Randolph, 2nd cornet, assistant director and arranger; Al Washington, tenor sax; George James and Lester Boone, alto sax; Charles Alexander, piano; Tubby Hall, drums; and Johnnie Lindsay, bass violin. Jackson also lists guitarist Big Mike McKendrick on banjo. [Eugene Chadbourne straightens out the “5 musical Mike McKendrick brothers” confusion]. They would work together for a year with only one personnel change, disbanding before Armstrong went as a solo to England in mid-1932..

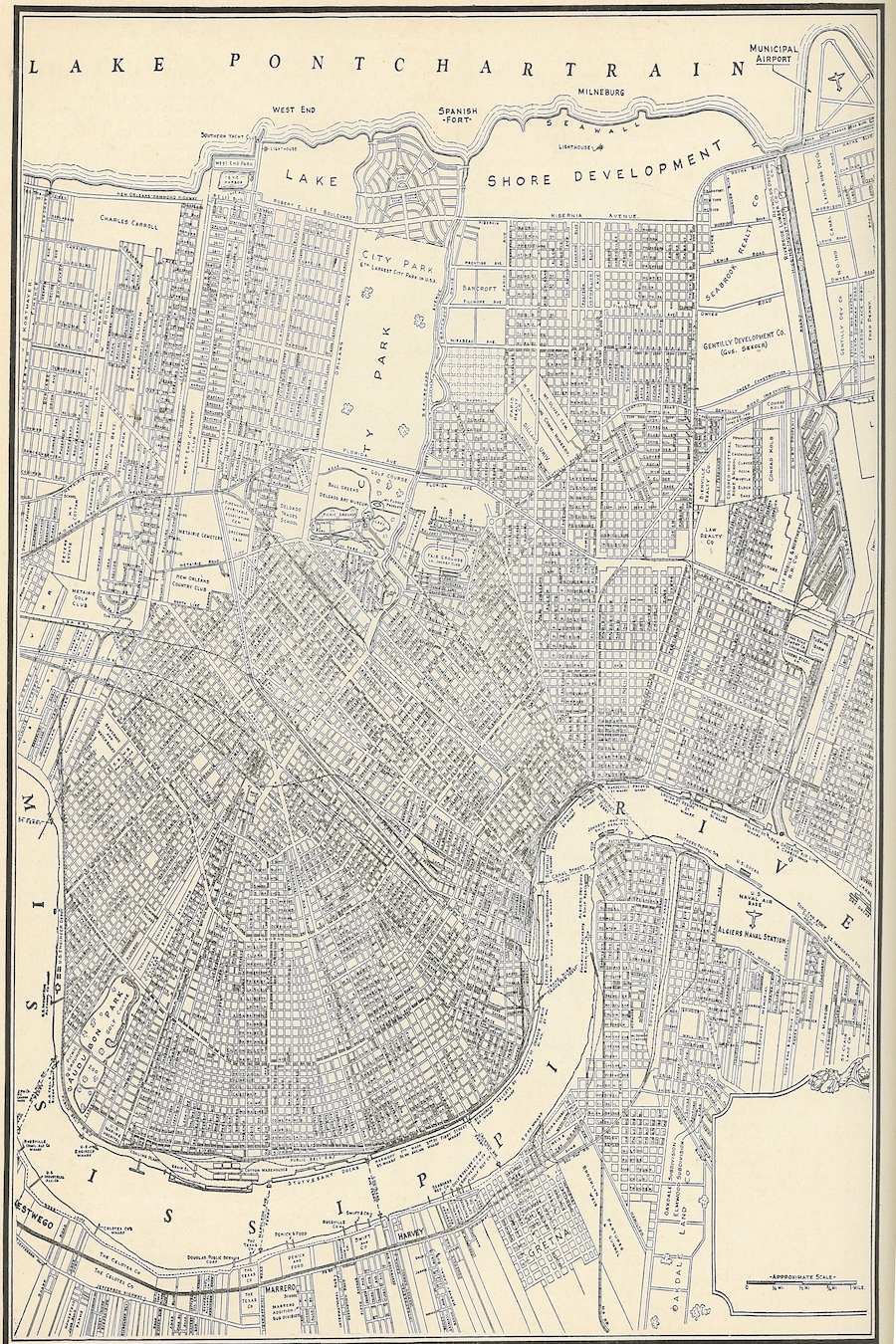

Back in Chicago after his gig at Sebastian’s New Cotton Club, Armstrong got involved in a contract dispute between Chicago and New York mobsters, but this time instead of honoring a “request”–really another threat–to return to New York, he headed to New Orleans, where he was to play an extended gig at the Suburban Gardens, a White’s only nightclub in what was developing as Metairie, near a bend in the Mississippi River. “We were supposed to stay there four weeks,” recalled Zilner Randolph, “and we stayed four months.”

Armstrong & his orchestra replaced Ben Bernie at the Suburban and also on WDSU radio.

So beginning in May, Armstrong and his band played one-nighters in Minnesota, Illinois, and West Virginia. In Cincinnati at the Greystone Ballroom, they played opposite McKinney’s Cotton Pickers, with Don Redmon directing, and at Ohio University, the yplayed on a 5-band bill that included Cab Calloway, Speed Webb, and Fletcher Henderson orchestras Kentucky before hooking a private rail car to a train in Louisville for New Orleans, where they arrived on June 5. This arrival and subsequent summer’s run in New Orleans is one of the most often recounted episodes of Armstrong’s life. Most of the many biographies of him rely heavily on Armstrong’s own memoir, a witty and entertaining book that stops too soon. So too does Tom Brothers’ excellent 2014 bio, Louis Armstrong: Master of Modernism, but Brothers also incorporates an impressive variety of primary sources, including unpublished and obscure narratives by others in Armstrong’s band, and accounts of their activities as noted in the Louisiana Weekly.

Trombonist Preston Jackson recalls that when “all these bands met us at the station, it was a regular parade.” Armstrong elaborates on the joyous scene in his memoir:

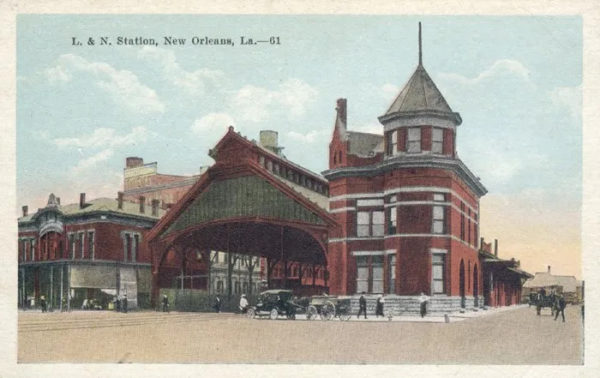

“We reached New Orleans early in June, and the last of the magnolias were still on the trees, the smell of them on the air. I did not know whether they had forgotten about me in all the time I’d been away, because I was just “Little Louie” Armstrong when I left and not too much account. But I soon found they had not. When our train pulled into the old L & N. Station out by the Mississippi, at the head of Canal Street, I heard hot music playing I looked out the car window and could hardly believe what I saw. There, stretched out along the track, were eight bands, all swinging together, waiting to give us a big welcome. As soon as I got off the train the crowd went crazy. They picked me up and put me on their shoulders and started a parade down the center of Canal Street. Those eight bands almost bust the town open, they made so much noise. Everybody had a good time and I guess the police did, too, because they didn’t bother us at all. When they had marched around through the city they took me to my hotel [the Patterson] for a little rest. . . I think that day was the happiest day in my life.

Built in 1902, the Louisville & Nashville Station at the foot of Canal Street was demolished in 1954.

The New Orleans Item provided a shorter narrative: Armstrong, it reported, “strolled South Rampart street” en route to play at the Astoria Gardens, and “police reserves kept the Negroes from mobbing him in their enthusiasm.” He performed “past midnight into the morning hours.”

Armstrong & his orchestra at the Suburban 1931.

Armstrong’s welcome to the Suburban Gardens a few nights later wasn’t so kind. The scene is dramatically re-created in the 2019 movie Bolden, with Armstrong’s exuberant performance juxtaposed with a dying Buddy Bolden listening to it on a radio in the asylum where he had been incarcerated for most of his life–and where he would die a few months later. Trombonist Preston Jackson is the main source of this version of the story:

On opening night, 10,000 Blacks lined the levee where the Suburban was located; inside, 5,000 or more Whites waited. Charles Nelson, the White m.c., comes out but says, “I can’t announce that [n]-man,” (or something to that effect) and leaves the building (or gets escorted out of it). Nonplussed, Armstrong asks the band for a chord, tells them to hold it, and introduces himself and then their first number, “Sleepy Time Down South.” Armstrong’s was not only the first Black band to play the Suburban, he often noted for the rest of his life that he’d been the first Black to speak live on a New Orleans radio station.

Photo provided by Preston Jackson to Mississippi Rag for publication in 1974 with Jackson’s recollections of playing with Armstrong.

Whether Buddy Bolden got to listen to Armstrong dedicate a song to him on the radio that opening night–as the movie depicts–isn’t known. But all New Orleans and much of the nation could hear the Louis Armstrong Orchestra nightly during that summer on late-night broadcasts that originated with NBC affiliate WSMB.

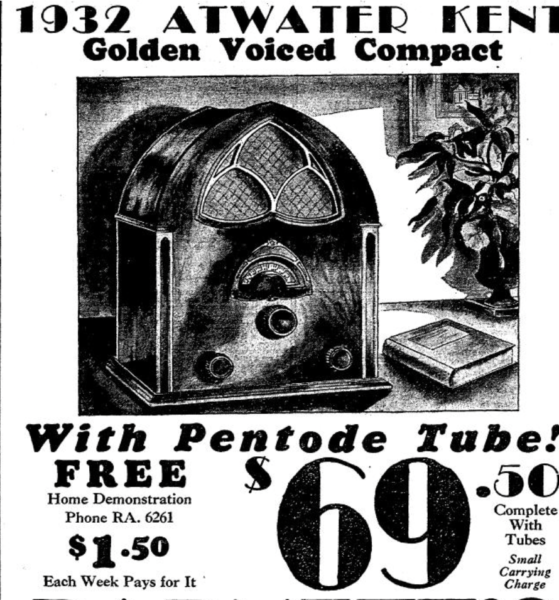

In 1931, a good radio was about 1/7 the price of a new automobile.

Evening radio shows on the city’s four most commercial stations–WSSMB, WDSU, WJSW, and WJBO–mixed music, news, children’s, and variety programming in the early evenings, but by 10 p.m. they were playing mostly music until sign-off. The city’s first radio station, WSMB, went on air in 1922; in June 1931, Radio Digest named it the city’s most popular. It appears to have had a contract to air live shows from the Suburban; Armstrong and his orchestra began their summer radio run on the air on June 10.

In 1931, both the New Orleans Item, which as a child Armstrong delivered and still read whenever he was in town, and the Times-Picayune ran daily listings of radio programming and also had radio critics (the States did neither) who wrote columns highlighting each day’s programming, both national and local, and made occasional comments on the local radio and music scene. The Item gave a little more coverage to news important to New Orleans’ Black community

The Item‘s Ted Liuzza in his June 10 column notes: “Louis Armstrong’s recording orchestra will waft torrid dance tunes onto the ether over WSMB. This broadcast is by remote control.” For the rest of the summer, Louis Armstrong and Orchestra is listed for performances, usually beginning at 10:30, in the Item. (Some performances are listed at 10 p.m. or 10:15. How long they usually ran is not clear, as most often they were either followed by another orchestra listed for 11:00 p.m. or were the last listed program for the day. Exceptions include June 20, when Armstrong’s orchestra is listed for 10:45-11:30 p.m.)

On August 22nd, Liuzza wondered, “Have you noticed how many local orchestras and their vocalists have tried to copy the ‘technique’ of Louis Armstrong and his band?” On the 26th, he announced that Armstrong “would play his last program on WSMB tonight.”

The Times-Picayune, on the other hand, never listed an Armstrong orchestra performance on WSMB by his name, despite otherwise running virtually the same radio listings in the same format as that of the Item. The T-P‘s radio critic, Jack T. McCully, made clear his taste in music a few days prior to Armstrong’s arrival in New Orleans when he wrote: “Listeners who have contemplated dynamiting their radio sets, or doing something equally awful to them because of the large amount of jazz they have been passing out these last several weeks, should shelve those ideas and give the old set another chance. Jazz is going to be ‘taken for a ride’ tonight and its domain will be invaded largely by the classics.”

In ignoring Armstrong’s initial radio appearance, McCully instead highlighted for June 10 a concert by a local but unnamed harmonica and banjo band. And for the entire summer, whenever the Item lists “Louis Armstrong Orchestra,” the T-P lists simply “Orchestra” with times.

The Suburban, in a new location, was huge, with a dining hall and casino as well as a dance hall where Armstrong and his orchestra were the only entertainment, performing 40 minute sets for six hours, with Mondays off. Armstrong himself was spectacular–he once “stepped out to the center of the dance floor,” Brother writes, “for 20 choruses of “Tiger Rag”–and the house was usually full, with large numbers of Blacks gathered on the levee to picnic and listen. (Summers in New Orleans: all the windows open, and more than one interview subject in the fascinating collection of oral histories at Music Rising at Tulane University has commented about the city’s soundscape before so many noise machines would pollute it–how a trumpet sound could travel through the city, could cross the Mississippi.)

Robert Goffin describes further pyrotechnics: “One night the crowd went insane when Al Washington held a note without interruption for 13 minutes on the clarinet. . . Hats, gloves, purses, all sorts of objects rained at his feet.” Armstrong answered the challenge with “a series of 50 skyscraping notes.” Goffin’s bio is, perhaps, not so much reliable as it is fun to read, as in his description of Armstrong’s first notes at the Suburban: After the curtain went up, Armstrong “mouthed his trumpet–closed his eyes–and the Black angels soared above the heads of the White multitude.” A British jazz aficionado, Goffin also has some trouble understanding the Jim Crow South, as evidenced by his description of the Suburban scene, with so many Whites inside and all the Blacks except for servants and musicians outside, out of sight on the levee: “Who would have dreamt that thousands of New Orleanians, flouting for the nonce the ancient law of segregation, would gather willingly in one place to listen to a Black man’s music? The old aristocrats deplored the painful situation.”

Some of those aristocrats were certainly offended by at lease one Armstrong quip. When he told someone on-air who wanted to hear a particular song that they’d “take that baby like Grant took Richmond,” it generated enough complaints that Armstrong apologized during the same set. That’s Preston Jackson’s recollection. Or was the remark made, as Zilner Randolph recalls, in urging listeners to come out quickly to a Pelicans baseball game?

Jackson recounts several incidents indicative of “the troubles we had in the South.” Arrests in Memphis and St. Louis were perhaps the worst; their “first real trouble in New Orleans” was at the Suburban: “Louis usually did a specialty, then retired to the dressing room while the band played a few numbers, with Zilner Randolph conducting the band in his absence. One night during Louis’s absence a beautiful young woman who was slightly intoxicated grabbed Randolph’s hand as he was directing the band, and said “I love you Black man, I love you.” Randolph was surprised, and he could not shove her because she might fall and hurt herself. Finally he was able to free his hand, but he had stopped conducting and the band didn’t know what to do. We quickly filed off the stage and went up to Louis’ dressing room, where Louis was taking things easy. We told him what had happened and that we were afraid to go back.” But club owner soon appears, said everything was “all right, and that the audience had taken up a collection for the band.”

As if to further demonstrate the difficulty of relying on memories for factual narratives, Zilner Randolph describes the same scene to a 1974 interviewer:

After Louis had left the stage for a rest, Randolph recalls, “The floor was just crowded. So I was up playing and directing the band, and after a while somebody just grabbed my hand. And I had my back turned to them, see, and they had my hand, holding it, you know. Floor was crowded. Then I noticed a look on the boys’ –and the boys looked, I said, “who’s that got hold of my hand, and why are those guys looking so funny?” So when I turned around, this way, I turned around and there was this long-haired blond had hold of my had. She had hold of my hand, and then–I don’t jerk, I just come on and I kept my cool, you know. Of course, I was afraid if I’d jerk, it might jerk her down, see. . . And when they ended that number she turned my hand loose and we just walked right off the stand.”

Brothers reports that Armstrong tried three times to schedule performances accessible for Black patrons. A June 6 show at the Astoria Gardens was stopped by his Suburban Gardens contract; the 1,300 fans who showed up were not happy when he tried “to appease them by singing three lines of “Peanut Vendor”; 29 were arrested. Then a July 8 Pythian Temple roof Garden show fell through, and finally, at the end of his stay, a much promoted final concert never materialized–more on that evening below.

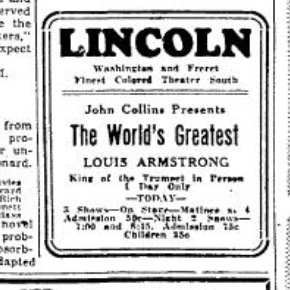

New Orleans Item June 13, 1931

Armstrong and his wife, Lil, were nearing the end of their relationship while they were in New Orleans, and she would go back to Chicago before the Suburban run was over (in his new car, with the bellboy from the Patterson Hotel, where they were staying). The show they did together on June 13 at the Lincoln Theatre turned out to be the only one that summer where Black audiences could sit inside and watch their hometown hero perform. Zilner Randolph was clearly moved by their performance: “Louis and Lil put on an act, honest to goodness, I had never seen such a superb act. That act was immaculate. Those two people performed. I didn’t know–they looked like they could just breathe together. They knew what one another was doing, and I said to myself, “It’s a shame that she’s not in some kind of show.” Well, they said she was a good dancer. But she didn’t do too much dancing, but just the witty little things that she and Louis would do. And she would sing, Louis would play the horn. Then, they would start ribbing one another and kidding one another on the show. And their act was–the band enjoyed it more so than the people did.”

Armstrong also made local news that summer by visiting, in late June, the Colored Waif’s Home where he had lived as a child. The waifs band serenaded him and he gave their home a radio so they could hear him dedicate a song to them on that evening’s broadcast.

In July, he was a pallbearer at the funeral services for his former mentor Buddy Petit, who was only four years older than Armstrong but whose trumpet playing Armstrong had, early on, imitated. Petit, Brothers writes, “played in a narrow range but with an expanded command of harmony, fast fingering, a gift for variations, and imaginative counterpoint to the lead; he was an example for Armstrong in all four areas.” But he was also an alcoholic, living in a one-room cabin on Lake Pontchartrain when he died on July 4. Randolph says that much of the crowd at Petit’s funeral and parade was there to see Armstrong.

In August, he visited the home of the Zulu Social and Pleasure Club, was made an honorary member, and subsequently sponsored their baseball team, which changed its name from the Superior Nine to Armstrong’s Secret Nine. He and the players serenaded Armstrong’s wife, Lil Armstrong, in the lobby of the Patterson Hotel, where they were all photographed.

Armstrong’s generosity was so legendary, bandsmen recall, that locals would wait for him to show up at the Patterson Hotel, where he’d hand out money to everyone in line.

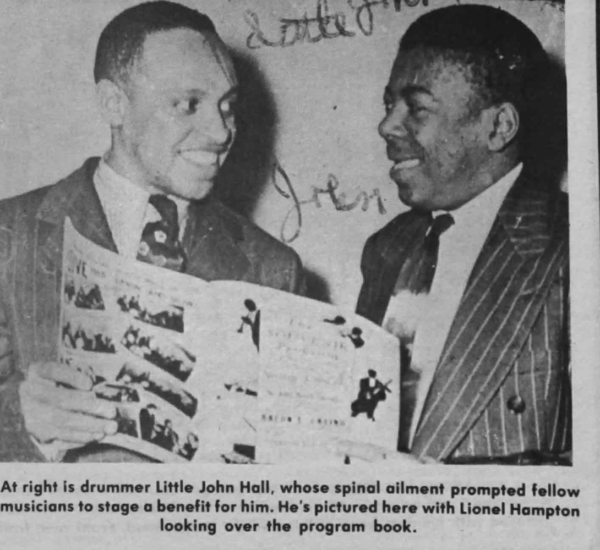

Mississippi Rag, 1974

Preston Jackson tells a charming story about his selling ads in a program to help raise funds for Little John Hall, 18, a Chicago drummer Jackson says was “one of the best,” but who had developed a spinal ailment. Armstrong bought a $20 ad: “Then he looked down and saw that my shoes weren’t as good as they should be because one sole was flopping around and I’d tied a bit of string round it to stop it flopping so much. ‘Nosey, you need some treaders, you are barefooted as a goose. Go and get yourself some treaders.’ And he handed me a 20 dollar bill”–enough, he adds, to buy 3 pairs of shoes.

Armstrong was honored that summer by Prof A. J. Piron, orchestra leader and proprietor of Piron’s Garden of Joy, who marketed a “Louis Armstrong Cigar.” Piron was also at the center of one of the worst nights of Armstrong’s summer, as recounted on September 19 by the Pittsburg Courier.

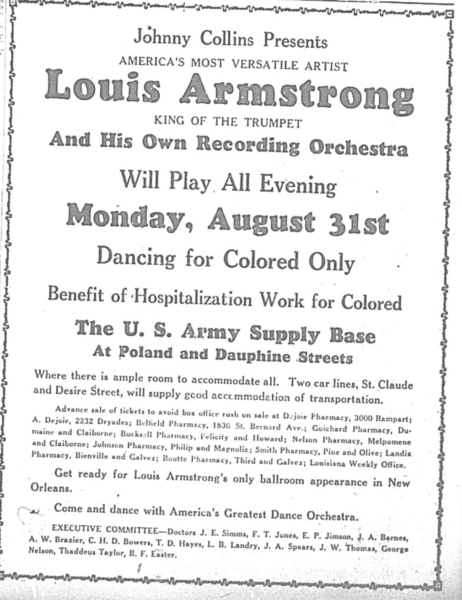

One of the summer’s events that never was.

The Courier also reported but it does not appear to be documented elsewhere that, after his Suburban engagement ended, Armstrong continued staying at the Patterson Hotel, “playing scattered engagements” about town. Then, on his last night in New Orleans, he was to play at a farewell dance that went awry.

This “colored only” event, long anticipated because of the general inaccessibility of Armstrong’s orchestra for his local Black fans, was set for August 31, at the U.S. Army Supply Base near the Industrial Canal. “Hundreds” or “thousands” came out only to find padlocked gates. Whether because the Army wouldn’t allow dancing or local clubs had intervened depends on who’s telling the story. The National Guard was called in and, Laurence Bergreen writes, “drove away the bitterly disappointed crowd with drawn bayonets.” The angry crowd cursed Armstrong, and as the band drove away, “Louis wept.” In this version, the “next day” the band leaves town on is September 1, not the 15th.

Trombonist Preston Jackson recalls that Armstrong had for this last evening in town “rented a government warehouse and hired a piano from Werlein’s”; Randolph suggests that the trouble with using the rented hall was because of troubles Armstrong was having with the local union; Jackson thought the difficulty “a political move,” as an Armstrong show that night would have hurt business at the nearby Astoria and Pythian Temple. He adds, “Rampart Street was loaded, as people had come all the way from Arkansas and Texas. I never saw so many Model T Fords in my life. The place was just crawling with people with no place to go.” Armstrong said in his 1954 memoir that he still didn’t know what had gone wrong.

Armstrong and his orchestra left the next day for Texas, promising to return to New Orleans on their way back to Chicago.

Armstrong had proved to be a consistent news generator wherever he went or said he was going to go, and national news accounts easily confuse timelines: both the Chicago Defender and Pittsburg Courier reported on Armstrong’s summer activities—and the complications surrounding them–but they don’t always include datelines or otherwise make it easy to figure out exactly when something might have happened. And then there’s the impossibility of knowing when a promoted event occurred–all of which makes something like Tom Brothers’ book all the more remarkable for its coherence, and he sums up Armstrong’s homecoming nicely: “Regardless, Armstrong had an amazing but bittersweet summer. The three months in New Orleans must have been immensely satisfying, except for the glaring fact that the people who had nurtured him, musically, and otherwise, during the first 21 years of his life were not allowed to hear him play.”

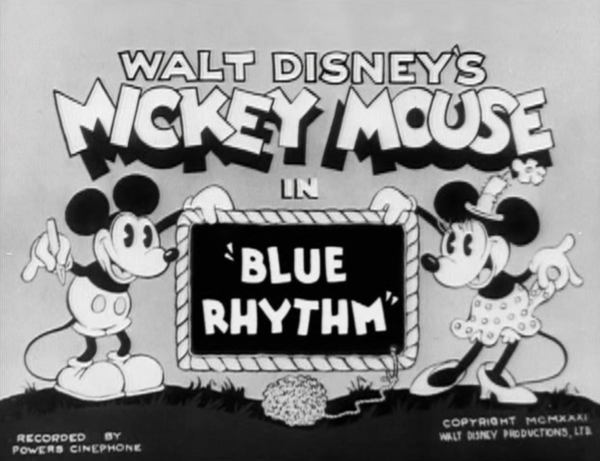

Watch Mickey Mouse’s 1931 cartoon, with a Louis Armstrong & band soundtrack.

From New Orleans, the band embarked by bus on a grueling 6-week tour of 1-nighters in the South and Southwest–with police incarcerations in Memphis and St. Louis–before heading back East, to New York and then Boston, where they whipped the Casa Loma and Fletcher Henderson orchestras in a big battle of the bands. Back in New York afterwards, they made the soundtrack for two films, the 8-minute Disney cartoon “Blue Rhythm,” starring Mickey Mouse, who had just turned 3, and “Rhapsody in Black and Blue,” a 10-minute performance piece.

Despite intentions otherwise, Armstrong did not bring another band to New Orleans again util 1935.

Ξ Ξ Ξ

1935

Over the next three years Armstrong played big shows and for successful residencies in New York (including a stint in Hot Chocolates of 1932), Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Washington, DC. In England the Queen smiled at his music and the King, whom he called “Rex,” presented him with a golden trumpet. A second European tour ended with a long vacation in Paris before he returned to the U.S. in early 1935 and confronted, again, legal issues precipitated by his mob interactions.

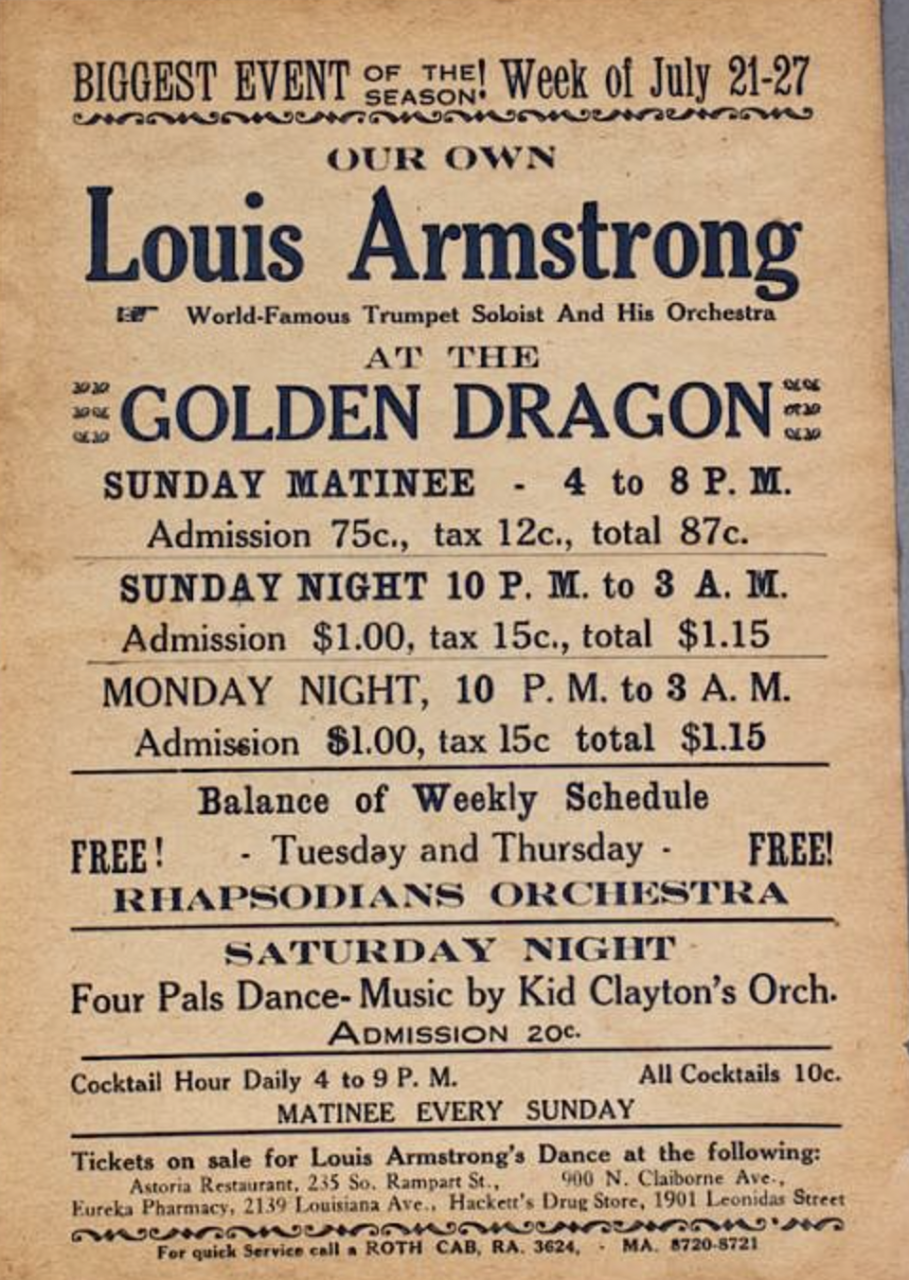

He also suffered lip issues that hospitalized him and left him unable to play for a few weeks before joining up with a band led by Zilner Randolph. They were welcomed back to New Orleans, Armstrong wrote, “with another nice parade–a bigger welcome than ever,” and played a week’s stand in July at the Golden Dragon. [One source says this was 2-night stand; Armstrong himself recalls that this homecoming happened in August.] The Chicago Defender contrasted Duke Ellington’s near-concurrent engagement at City Park, in which he played one show for Whites and one “for his own people,” by pointing out that Armstrong’s two shows would be for “anybody and everybody.”

He also suffered lip issues that hospitalized him and left him unable to play for a few weeks before joining up with a band led by Zilner Randolph. They were welcomed back to New Orleans, Armstrong wrote, “with another nice parade–a bigger welcome than ever,” and played a week’s stand in July at the Golden Dragon. [One source says this was 2-night stand; Armstrong himself recalls that this homecoming happened in August.] The Chicago Defender contrasted Duke Ellington’s near-concurrent engagement at City Park, in which he played one show for Whites and one “for his own people,” by pointing out that Armstrong’s two shows would be for “anybody and everybody.”

Armstrong hadn’t visited New Orleans since 1931, the Defender reported, in adding another version to that “last night” in 1931, “when a disagreement, never explained, prevented him from playing for some 8,000 enraged natives who had been excluded for three months from a White night resort in the suburbs. The police, ‘way back there’ had to be called out to prevent the hometown folks from showing too much welcome.”

Before leaving New Orleans this time, Armstrong went with a city welfare official to a music store and, as he did in 1931, bought an expensive radio for “some bad boys like myself” who may, some day, he said, become “bigger and better than me.”

Ξ Ξ Ξ

Why Armstrong skipped New Orleans but played the Odd Fellows Temple in Baton Rouge on his brief November 1937 tour is not clear. A motorcade of more than 50 cars made the trek from New Orleans to honor and welcome him.

Ξ Ξ Ξ

1938

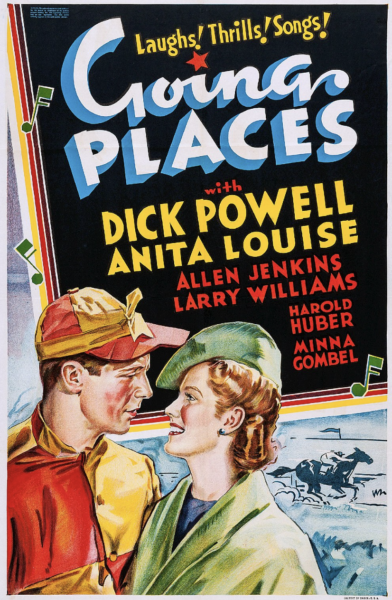

Armstrong appears to have tentatively scheduled performances in Baton Rouge and New Orleans during a tour that was interrupted in August by a call to Hollywood, where he spent a few weeks making the Warner Brothers comedy Going Places. In it, Armstrong sings “Jeepers Creepers,” which was nominated for an Academy Award for best song, to a horse.

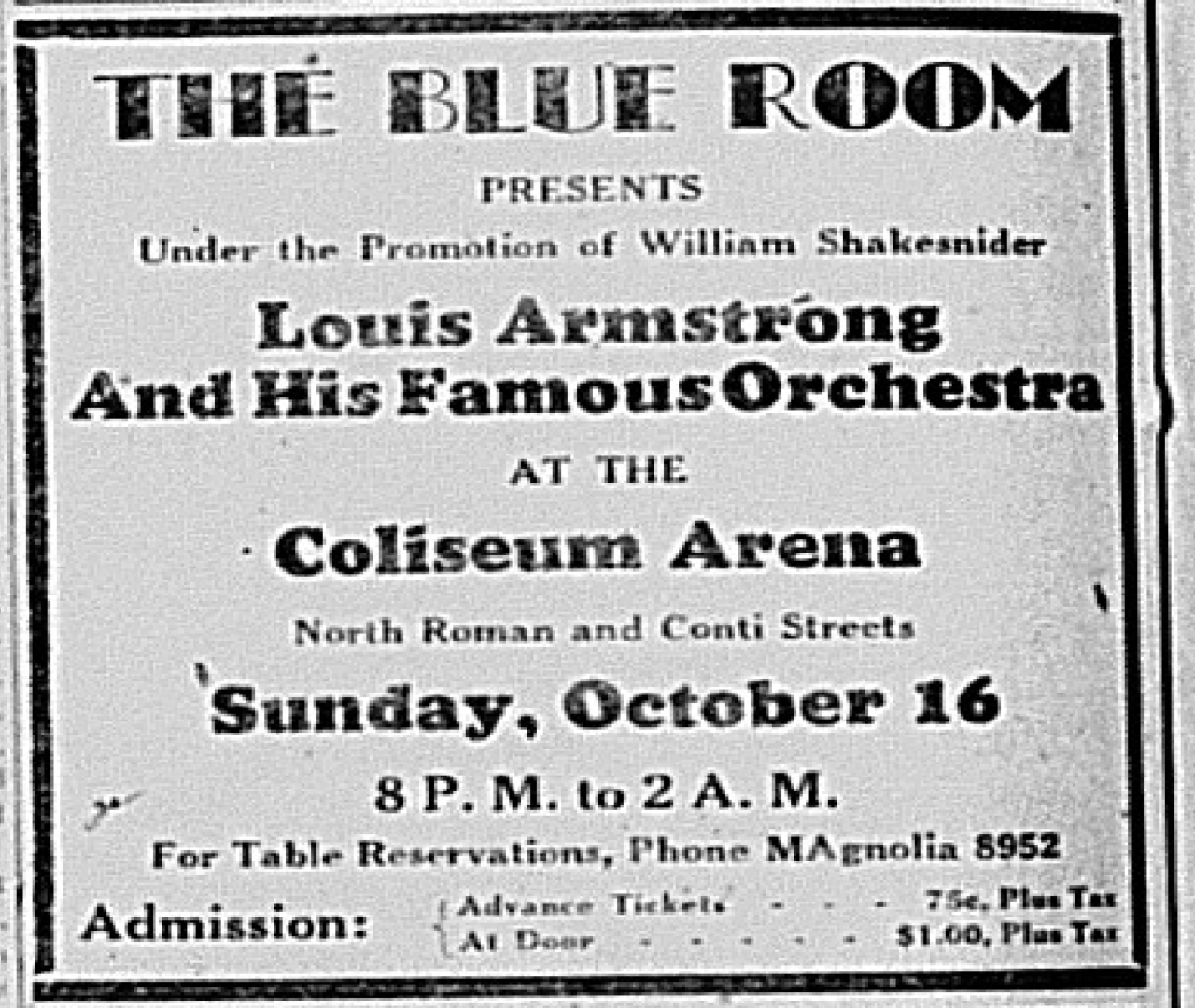

His concert at the Coliseum Arena in October 1938 marked the first time in three years he’d played New Orleans. It was also the first use of that venue for a non-boxing event. Promo promised “plenty of dancing space and accommodations,” and a “blueprint of seating” arrangements–a table with 4 chairs reserved for a dollar, 2 chairs for 75 cents, a fee apparently added on to admission–could be viewed at the dozen or so local businesses who sold tickets. Sonny Woods and Midge Williams were announced as vocalists with a band that also featured Henry “Red” Allen.

His concert at the Coliseum Arena in October 1938 marked the first time in three years he’d played New Orleans. It was also the first use of that venue for a non-boxing event. Promo promised “plenty of dancing space and accommodations,” and a “blueprint of seating” arrangements–a table with 4 chairs reserved for a dollar, 2 chairs for 75 cents, a fee apparently added on to admission–could be viewed at the dozen or so local businesses who sold tickets. Sonny Woods and Midge Williams were announced as vocalists with a band that also featured Henry “Red” Allen.

The Louisiana Weekly headlined its review of the show “4,000 Floy Floy to Louie’s Swing at Coliseum.” The Coliseum’s boxing ring had been replaced by a stage and “the dance-crazed fans swayed to the maestro’s fast, slow, and torrid swing, making a colorful spectacle.” The orchestra, “seething over with real hot jazz tunes put the crowd into a mad, rhythmic frenzy.” Highlight of the evening was the inauguration of “prominent undertaker” Joseph P. Geddis as “Mayor of Negro New Orleans,” whose escorts included several recent beauty crown winners. They and promoter William Shakesnider were Armstrong’s official welcoming committee.

Although not a sellout–the gallery was only “partly filled”–it seemed a good crowd, but the Pittsburg Courier reported that Armstrong’s hometown “has proven to be a jinx,” claiming that a recent show at Baton Rouge and this one in New Orleans had been for small crowds, without qualifying with actual numbers. The Louisiana Weekly reported that “the jitterbugs had a time” at the Baton Rouge show but offered no other details.

Louisiana Weekly October 15, 1938

The Defender noted that Armstrong’s Baton Rouge show in 1937 had lost money and that this one did, too, citing as primary cause the high admission charge of $1.00 (advance 75 cents), the same admission for an October 30 show with Duke Ellington’s orchestra, who set up “Duke Ellington’s Ticket Office” at 222 S. Rampart Street.

For entertainment dollars, the primary competition that evening would have been a dance played by Joe Robichaux’s orchestra, which had just returned from an 8-week tour of Cuba. Typical admissions for local orchestras–Robichaux’s, Sidney Desvigne’s, Henry Russ and His Rhythm Club Swingsters, Papa Celestin’s, Victor’s Music Masters–ranged from 10-30 cents. A small number of venues (with enough business or connections to advertise or otherwise be noted in the Louisiana Weekly) regularly produced dances–the Gypsy Tea Room, the Rhythm Club, the Tick Tock (225 S. Rampart, with a gym, the “only one of its kind in the South for Negroes”–10 cents a visit or $2 a month), and the Palace Theatre–most often with local orchestras but with occasional traveling acts. The “swanky” Elks’ Forest, at 1913 Harmony Street, opened on July 17, offering matinee and evening shows on Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays. Clyde Kerr’s orchestra opened the Lafitte Club in October 1937.

However, Eddie Burbridge, writing for the Louisiana Weekly, had already begun worrying about changing times: the “old town is kinda going for the beer taverns these days in preference to dance halls and night clubs,” where “a nickel in the slot for canned music” made for private dancing.

Marcus Christian described a typical scene for The Negro in Louisiana: “Behind the counters of beer parlors catering to Negroes are various types of brown women hostesses, always smiling, to take the orders from the habitues of the establishment. Customary order, a beer, 10 cents, if not that, a ‘cut’ drink of some type. The biggest sell 150 cases of beer a week.” Their floors are “sprinkled with shavings of aromatic cedar” or sawdust, and they have a “suitable arena for jitterbug ‘struggles’ that take place when a hot number plays on the ‘everlasting’ juke box, without which no self-respecting beer parlor would ever dream of doing business.”

Most popular is “swing music, nearly always played by nationally famous Negro orchestras, to the accompaniment of an emotional, despairing, rhythmic voice, sounding forth in a deep indigo-purple mood, affording the more melancholy patrons an excellent opportunity of crying in their beer. For a nickel dropped in the slot, one may hear the now-famous Ink Spots proclaiming to the world at large that they don’t want to set the world on fire—no, no—they only wish to start a flame in somebody’s heart, by, by. . . Groups of them stand hour after hour listening to popular recordings broadcasted to the passers. Nearby stores sell these ‘hot’ recordings.”

For Armstrong’s show, it’s also easy to imagine issues that might have arisen with accounting for profit with so many businesses selling advance tickets, and with the complicating factors of reserved seats being sold separately from admissions.

For Armstrong’s show, it’s also easy to imagine issues that might have arisen with accounting for profit with so many businesses selling advance tickets, and with the complicating factors of reserved seats being sold separately from admissions.

It’s unclear if the promoter, William Shakesnider, is also the excellent saxophonist (that both William and Wilmer Shakesnider are credited saxophonists on Ella Fitzgerald recordings seems to indicate there are not two players of the same last name); this Blue Room, at 134 S. Rampart Street, does not appear connected to the same-named White night club in the Roosevelt Hotel.

A return engagement announced for Armstrong for late 1938 did not materialize.

Ξ Ξ Ξ

1940

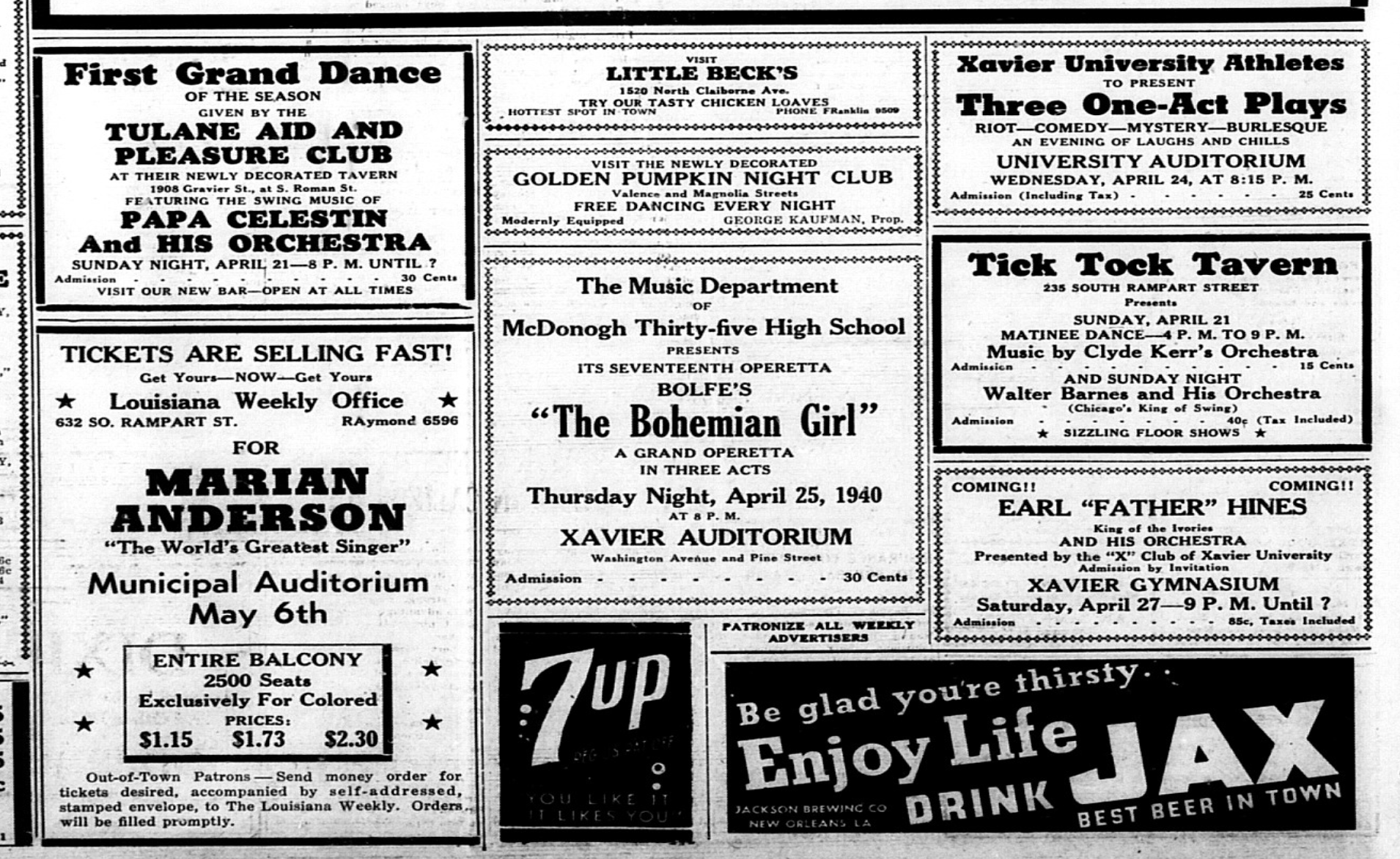

By late 1940, New Orleans was a much better city for live music, both locally and for traveling acts. In some ways, the Depression was a distant memory, at least on the surface, as reflected in a thriving night life. By the time Armstrong arrived, in November, nearly a dozen venues were regularly presenting dances with local orchestras and hosting traveling acts. Battles of the bands raged: little David Bartholomew was likely the cause Cobojo declared Fats Pichon victor in a battle against the heavily favored Sidney Desvigne. “Little David,” wrote Cobojo, “plays a mean trumpet, instead of a harp.” New to Pichon’s orchestra, he “was clicked at the Rhythm Club. . . a sender on the brass with a style similar to Erskine Hawkins.”

The year started strong musically, with Nina McKinney at the Tick Tock in January. By the time Ella Fitzgerald played for the grand opening of the Rhythm Club in June ($1.15 admission), Walter Barnes, Fatha Hines, Marian Anderson Joan Lunceford, and Ida Cox with their bands had all played New Orleans. The Astoria Restaurant was open 24/7. The Patterson Hotel, with “40 modern rooms,” opened in October; Louis Messina was re-vitalizing the Gypsy Tea Room, and sports promoter Allen Page took over the Riley Hotel. Page had been responsible for bringing a Negro League All-Star game to New Orleans in 1939 and for getting the St. Louis Stars to move there in 1940; he and Messina were the dominant promoters in the early 1940s of big sporting and entertainment events for New Orleans’ Black audiences.

Armstrong’s November 17 engagement at the Rhythm Club delighted Cobojo: “Louis Armstrong trucked into town with a bandwagon of tooting, jiving, joking music hipsters, a bunch of solid senders from way back, all the cats were there, mooching and jitterbugging. One giggle water crazed chick jumped on the bandstand and attempted to stop the drummer from beating his kings. Cutting out now.”

⊗

Louisiana Weekly April 20, 1940

1942

While in Los Angeles in April 1942, Armstrong made 4 soundies, including “Swingin’ on Nothing,” with Luis Russell’s band and vocals by Velma Middleton and trombonist George Washington. Be sure to watch to the end, for the grand finale!

His return to New Orleans in August 1942 was a triumphant homecoming, his big concert and dance among the last celebrations members of New Orleans’ first Black Navy band would witness before they left for training in Chicago.

Sources

Armstrong, Louis. Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans. 1954. Boston: Da Capo, 1986.

—. Swing that Music. 1936. Boston: Da Capo, 1993.

Barnes, Jr. , Walter. “Hittin’ the High Notes,” Chicago Defender 5 Dec. 1931.

Bergreen, Lawrence. Louis Armstrong: An Extravagant Life. New York: Broadway, 1997

Brothers, Thomas. Louis Armstrong: Master of Modernism. New York, Norton, 2014.

Chadbourne, Eugene. “‘Big'” Mike McKendrick Biography.” n.d. allmusic.com 24 July 2023.

Christian, Marcus. “The Negro in Louisiana.” Marcus Christian Collection. Huey Long Library, U of New Orleans.

Cobojo. “Out on the Limb.” Louisiana Weekly. 26 Oct. 1940: 4; 23 Nov. 1940: 4.

Curbridge, Eddie. “After Sundown.” Louisiana Weekly. New Orleans. 15 Oct. 1938: 4.

Davis, Emily C. “Louisiana State: New Orleans News.” Chicago Defender. 22 Aug. 1931 P#

“4,000 Floy Floy to Louie’s Swing at Coliseum.” Louisiana Weekly. New Orleans . 22 Oct 1938: 4.

Goffin, Robert. Horn of Plenty: The Story of Louis Armstrong, New York, Allen, Towne & Heath, 1947.

“Home town has proven jinx town for Louis Armstrong.” Pittsburg Courier 8 Oct. 1938: 20.

Jackson, Preston. “Reminisce is the Word: My years with Louis Armstrong,” Mississippi Rag 1.10 (August 1974): 6-9

—. Trombone Man: Preston Jackson’s Story as told to Laurie Wright, Essex, England: L. Wright, 2005

Jones, Max & John Chilton. Louis: The Louis Armstrong Story, 1900-1971. Boston, Da Capo, 1971.

“Louis Armstrong Coming” Pittsburgh Courier 24 Sept. 1938: 18.

“Louis Armstrong Had No Place to Toot His Horn, Crowds Followed.” Pittsburgh Courier 19 Sept. 1931: A8.

“Louis Armstrong to Play for ‘Jitterbugs’ at Coliseum, Sunday October 16.” Louisiana Weekly. New Orleans. 24 Sept. 1938: 4.

“New Orleans Hosts to Two Great Orchestras.” Chicago Defender. 13 July 1935: 7.

“New Orleans Plans Motorcade to Baton Rouge for Armstrong,” Chicago Defender. 5 Aug 1937: 5.

Randolph, Zilner. Interview by Don de Michael. Chicago. 20 Feb. 1974. Rutgers U Libraries. Newark, NJ.

Riccardi, Ricky. Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong. New York: Oxford UP, 2020.

Whirty, Ryan. “Negro Leagues all-stars were a big hit in the Big Easy in 1939,” 1 Oct. 2009. nola.com. 22 July 2023.

—Alex Albright

July 26, 2024

1940 New Orleans