–this page is under construction–

Another Fool’s Errand: An Unpleasant & Mostly Forgotten Past Unfolds

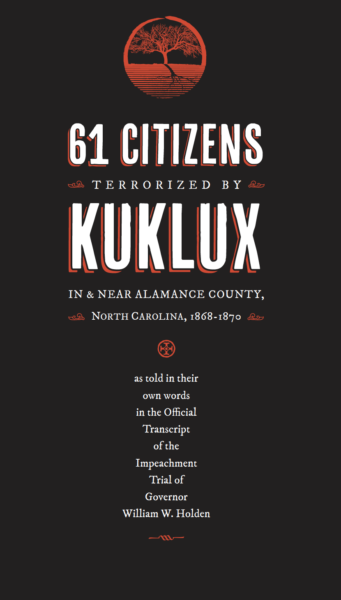

I’ve said the 61 names out loud many times. Two are testifying about the murders, respectively, of a son and a brother, the only two named in William Powell’s standard history of North Carolina. Wyatt Outlaw and Sen. John Stephens were politicians, one in Alamance, the other in Caswell County, each murdered by Kuklux as part of the terror campaign that ultimately restored White rule.

The other 59, regular citizens, are the kind, obviously, that don’t make history books—a wheelwright, a cobbler, blacksmith, a nightwatchman, a couple of teachers, a grandma watching her granddaughter play—all trying to negotiate what had turned out to be much more perilous than they’d thought freedom would be.

The 36 Black citizens who testified at Governor Holden’s impeachment trial about their mistreatment by Kuklux were all born into slavery. As if to highlight a rebelliousness that might have warranted their treatment by Kuklux, their personal history with being whipped is of great interest to the prosecution. “Have you ever been whipped before?” they are often asked, as if an affirmative answer might help explain the current complaint.

Three of the 36 have no idea how old they are (White witnesses are seldom asked their ages and never asked their personal history with whippings, except for those they might have witnessed or participated in); three others make a good guess; several announce proudly their birthdates. The oldest to testify, Jemima Phillips, who was also Wyatt Outlaw’s mother, was born in 1798; the youngest, Damon Holt, was 16 when he and two other teenage boys were taken by Kuklux from a Christmas party and whipped with hickory sticks; what happened to one of those three after his whipping isn’t known.

What were you whipped with? is also a common question put to the witnesses: cedar, sweet gum, red elm, peach, hickory, shaved hickory, black jack, dogwood, persimmon, a plaited switch, a wagon whip with a leather strap attached at its end. Only two of those who were whipped don’t know what they were whipped with. Several describe the splinters taken from their backs, the broken sticks left behind by their attackers.

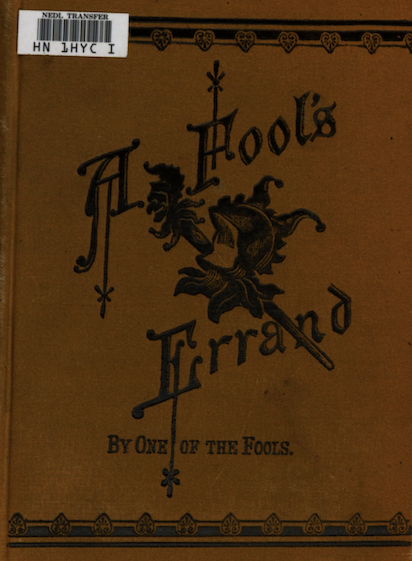

Atrocities described by Alamance citizens and the resultant terror in which they lived in 1878-1870 are, of course, the reasons for this book. Without these “true testimonies of incredible barbarity”—as Albion Tourgee described some of them in his 1879 novel A Fool’s Errand—there’d be no book. They are, as Tourgee wrote, “too horrid to print, but too true to omit.”

Atrocities described by Alamance citizens and the resultant terror in which they lived in 1878-1870 are, of course, the reasons for this book. Without these “true testimonies of incredible barbarity”—as Albion Tourgee described some of them in his 1879 novel A Fool’s Errand—there’d be no book. They are, as Tourgee wrote, “too horrid to print, but too true to omit.”

But 61 Citizens is more than an enumerating of barbarous actions that should not ever have happened human upon human. Its chronological arrangement helps chart the progress of Kuklux actions as they become more brazen, violent, shameless. But extended testimonies offer humanizing contexts as they reveal the speakers’ daily lives in strong and original language that’s sometimes lush, naturalistic, poetic, usually in precise and calm detail. Their strength of character is revealed also in how they respond to the callous and often demeaning questioning they receive from prosecution attorneys, William Alexander Graham especially.

First drafts of 61 Citizens focused on briefer accounts, more violence. A printed book wasn’t even a thought. I thought it would ultimately make a good web resource, its first working title not 61 Citizens but 33 Colored Citizens. No story but that of the violence done to them can be attached to the names of the eleven whose names were moved to an appendix, and as that edit was made, those testifying got more and then more room to tell their stories from their unique perspectives. In their telling, another 92 citizens are added to the primary list of 61 citizens. The book’s longer and more descriptive excerpts of the trial, I believe, build character into the speakers the way a successful novel might, especially in the kinds of details they recall and in the archaic language they often use in recounting those details (I think here of how Charles Frazier so expertly used language of the period for his Civil War novel Cold Mountain), and as they grew longer and longer in the manuscript, I finally escaped the somewhat common misconception that the Klan’s targets were almost always Black people. The attacks, I came to understand, were on the idea of Black suffrage and civil rights. Just the thought of it turned the ones who took up disguises into monsters for whom no deed was too awful to commit.

My arrival at a chronological order in which to present the testimonies presented a serendipitously symbolic first narrative, that of a White man, Leonard Rippey, who stops at the home of a Black man, Jake Brannock, to get his wagon wheel repaired. He admits to the Kuklux who’s put a pistol to his face that he could have probably found a White man’s house at which to stay the night. His trip to deliver molasses, interrupted because of a broken wheel, becomes a nightmare: the reason he’s whipped? For being “a d—-d old radical.”

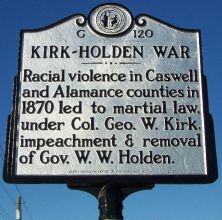

The November 3, 1868 election of U.S. Grant as President, and Holden’s ascendent power quickly became too much, too threatening to the social and political order represented by the White supremacists who controlled Alamance. Hence the events recounted in the rest of this book, the Kirk-Holden War, the impeachment and removal from office of Governor Holden, the collapse of Reconstruction, and the return of home-rule to the states.

• • •

Growing up White in Alamance County gave me no knowledge of those awful months of terror that preceded the Kirk-Holden War. Of that affair, I learned little more than the text on the historic marker that still stands a block away from my Marshall Street home. Like most of my peers, the history I learned was about the sanctity of our Lost Cause, how valiantly our ancestors had fought against the invading, marauding Yankees, and how all across our land we had erected giant Confederate soldiers and positioned them, every one, facing North, to guard against the next invasion. That so many White people grew up in Alamance County without any knowledge of the atrocities that preceded the Kirk-Holden War is more than a sad failure of our education system. It’s also an early draft of what motivates those today who wish to control the historical narratives of the United States, who misread and mis-label the 1619 project, who cry “fake news” and “stolen election.”

Like most of my peers, the history I learned was about the sanctity of our Lost Cause, how valiantly our ancestors had fought against the invading, marauding Yankees, and how all across our land we had erected giant Confederate soldiers and positioned them, every one, facing North, to guard against the next invasion. That so many White people grew up in Alamance County without any knowledge of the atrocities that preceded the Kirk-Holden War is more than a sad failure of our education system. It’s also an early draft of what motivates those today who wish to control the historical narratives of the United States, who misread and mis-label the 1619 project, who cry “fake news” and “stolen election.”

I was a top ten senior at Graham High School, class of 1969 (the first to integrate) and a keen student—or so I thought—of local history. But Wyatt Outlaw’s story was the first I knew of what went down in Alamance during those horrible months after local Whites were no longer restrained by the presence of Federal troops. His is, in some ways, the most horrific; but in the story of his lynching at the county courthouse, it’s also tempting to start categorizing what was done to whom by the level of violence. Murder, of course, is worse than assault; laws clearly make that clear. But when the intent of the assault is more to terrorize anyone who might support Black civil rights than it is to inflict pain on any individual, this narrative gets complicated. This is the terror felt by children made to stand outside in the cold by a fire consuming their family’s personal property while their dad is being gleefully whipped in their front yard.

• • •

The first of eight charges against Governor William W. Holden in his 1871 impeachment trial: he “corruptly and wickedly declared the county of Alamance to be in ‘insurrection.’”

The second charge: he did the same in Caswell County.

Alamance and Caswell were the fifth and sixth counties to earn this horrific designation, but it was Alamance that seemed always to be the epicenter of trouble. Holden’s impeachment trial would reveal that the Alamance sheriff and all of his deputies–each in charge of a precinct–were Kuklux. Almost a fifth of the 4,000 Kuklux in the state lived in Alamance, even more in Guilford, and several incidents testified to in his impeachment trial indicated nightriders had come out of Guilford to stage raids in Alamance, where it was so easy to get away with, literally, murder: Holden counts six Kuklux murders in Alamance, two in Caswell, and more than a hundred citizens taken from their homes and “scourged” because of their race or political opinions, during the reign of terror.

Holden became governor twice in less than six tumultuous years before his impeachment and removal from office in March 1871. He was appointed provisional governor in May 1865 by President Johnson, then defeated in the first post-Civil War election by Jonathan Worth. In 1868 as the Reconstruction Acts restructured the state’s government in preparation of its return to the Union, Holden was elected in a landslide, with extensive support from African American voters. Worth, who especially resisted the idea of Negro suffrage that the Reconstruction Acts guaranteed, at first refused to leave office, then said that he was leaving “under Military duress” and “without legality.”

After completing its new constitution in July 1868, North Carolina with Holden as governor was re-admitted to the union; the subsequent removal of military rule ended the protection that local citizens had enjoyed. Within three months of taking office, Holden was hearing of Kuklux violence throughout North Carolina. By that fall, violence and threats had become worrisome enough that Holden issued an executive order intended to protect all voting rights. In November 1868, in a pattern that many whites found alarming, voters in some parts of North Carolina elected candidates who were African American or sympathetic to their rights, and African Americans voted in large numbers. Attacks in those areas, such as Alamance and Caswell counties, increased soon after the election, and by early 1869 they were rampant.

Governor Holden persistently tried to protect citizens from these violent outrages. In April 1869 he issued an executive order prohibiting masked vigilantism and an appeal to all citizens of the state to join him in “discountenancing disorders and violence of all kinds, and in fostering and promoting confidence, peace and good-will among the whole people of the State.” The attacks worsened. In October, he declared Lenoir, Jones, Orange, and Chatham counties to be in surrection. In eighteen months, he issued four proclamations, wrote to members of Congress and President Grant and to U.S. military officers asking for assistance with controlling the Kuklux, and authorized sending military officers and detectives into the afflicted areas to file detailed field reports. Finally he asked the legislature for the right to call a county in “insurrection” and to protect its citizens with state’s military rule, and on January 29, 1870, the Shoffner Act gave him that power.

The act’s author, Senator T.M. Shoffner of Alamance County, subsequently fled for his safety, leaving Holden short another of his political supporters.

Meanwhile, the violent assaults continued. Wyatt Outlaw’s murder at Graham, on February 26, 1870, finally brought Holden to declare, on March 7, 1870, Alamance in to also be in state of insurrection, but it was July before the militia, led by the former Union guerilla leader George W. Kirk, restored safety to the areas. The Kirk-Holden War commenced on July 15, when Kirk began directing the arrest of local white men for, among other crimes, Outlaw’s murder. Eighty-two were arrested in Alamance, nineteen in Caswell. Complaints over their treatment at the hands of militia would constitute five of the other six impeachment charges against Holden. Holden’s supporters suffered big losses in the August 1870 elections; later that month all those arrested by Kirk were released on judge’s order, effectively ending the “war” although it wasn’t officially terminated until November. Immediately after the election, conservative press began calls for Holden’s impeachment, and after the new legislature was seated, it moved swiftly.

Articles of impeachment were introduced on December 9 and adopted on December 19. Holden left his office on December 20; two days later, he and his wife were baptized.

To pay for his defense, by attorneys in-private-practice Richard Badger, Nathanel Boyden, Edward Conigland, J.M. McCorkle, and William N.H. Smith, Holden mortgaged his Raleigh home. The House of Representatives first elected seven managers from among its body to conduct the prosecution, but Thomas Sparrow, appointed chairman of the board of managers, was the only elected official to actively participate in the prosecution. Instead, the state paid for its own high-powered attorneys to prosecute Holden: former governors William A. Graham and Thomas Bragg, who were also former congressmen; and Augustus S. Merrimon, who had been a superior court judge since the end of the Civil War.

The impeachment trial began in the senate chamber in Raleigh on January 23, 1871; on March 22, Holden was acquitted of the two most serious charges, that he had improperly declared insurrections in Alamance and Caswell counties, but convicted on the others, resulting in Tod Caldwell becoming governor and Holden leaving the state. A U.S. Senate committee investigating the reports of race violence in the South used some of the impeachment testimony but also documented extensively instances of similar Kuklux violence throughout the region. It also concluded in March 1871 that there were no serious problems between the races in the region. By March 1873, all alleged participants in vigilante assaults in North Carolina were pardoned and given amnesty from future prosecution. The Compromise of 1877 gave Rutherford B. Hayes the U.S.presidency, formally ended Reconstruction, and recognized “home- rule,” or the individual states’ rights to control their African-American population, with that power according to North Carolina’s constitution generally enforced by county sheriffs.

• • •

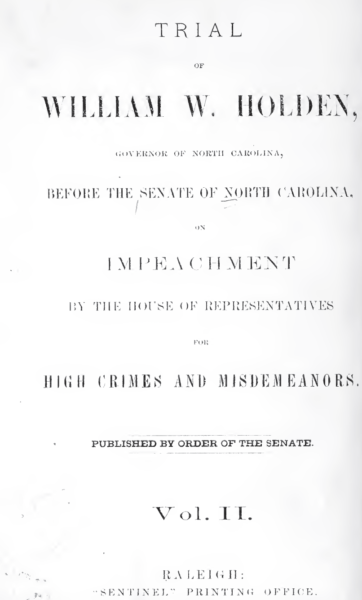

The official transcript of the impeachment trial is part of a three-volume set of government publications. The first, a 400 page document published as Argument in the impeachment trial of W.W. Holden, governor of North Carolina, introduces the case against Holden.

The official transcript of the impeachment trial is part of a three-volume set of government publications. The first, a 400 page document published as Argument in the impeachment trial of W.W. Holden, governor of North Carolina, introduces the case against Holden.

Holden then authored his defense, which the state published as a 46-page document, before the trial commenced.

The 3rd in the trilogy of the official impeachment documents, about 1500 pages, contains the bulk of the trial transcript, including the testimonies most relevant to the activities of Kuklux that resulted in the counties of Alamance and Caswell being declared in insurrection. This is the document from which the testimonies included in 61 Citizens is taken. It ends with day 36 of the 42 day trial and as the prosecution claims to be at the end of its presentations.

–January 2023